Cultural Defence and Culturally Motivated Crimes (Cultural Offences)

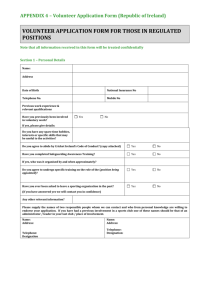

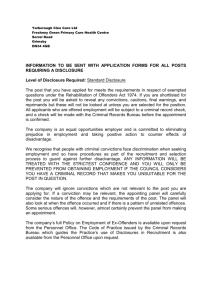

advertisement