CHS 218 - Community Health Sciences

advertisement

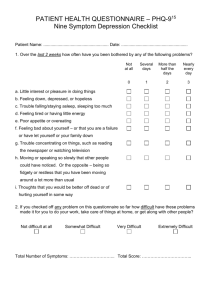

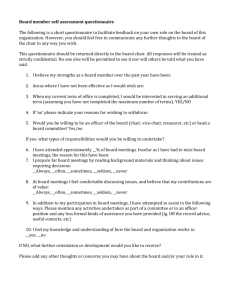

COMMUNITY HEALTH SCIENCES/EPIDEMIOLOGY M218 Questionnaire Design and Administration Course web site: http://www.ccle.ucla.edu/ (Moodle server) Day & Time: Mon & Wed 8-10 A.M. Room: CHS 41-235 ID#: 840 108 200 (CHS) 844 110 200 (EPI) Instructor: Linda B. Bourque Office: 41-230 CHS Office Hrs: Mon & Wed 10:00-11:30 Sign up for appointments on sheet outside office. TEXTBOOKS: A. Required books available for purchase in the Health Science Bookstore: 1. 2. 3. B. Recommended books available for purchase in the Health Sciences Bookstore. 1. 2. 3. 4. C. LuAnn Aday, Designing and Conducting Health Surveys, 3rd edition, JosseyBass, 2006. Linda Bourque and Eve Fielder, How to Conduct Telephone Surveys, The Survey Kit, Sage Publications, 2nd Edition, 2003. Materials available on course website and UCLA Biomedical Library Reserves. Linda Bourque and Eve Fielder, How to Conduct Self-Administered and Mail Surveys, 2nd Edition, The Survey Kit, Sage Publications, 2003. Linda Bourque and Virginia Clark, Processing Data: The Survey Example, Sage Publications, 1992. Jean M. Converse and Stanley Presser, Survey Questions, Sage, 1986. Orlando Behling and Kenneth S. Law, Translating Questionnaires and Other Research Instruments, Problems and Solutions, Sage Publications, 2000. Recommended books available in the UCLA libraries: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. Arlene Fink, How to Ask Survey Questions, The Survey Kit, Sage Publications, 1995, 2nd edition, 2003. Arlene Fink, How to Design Surveys, The Survey Kit, Sage Publications, 1995, 2nd edition, 2003. Eleanor Singer and Stanley Presser, eds., Survey Research Methods, A Reader, The University of Chicago Press, 1989. Donald Dillman, Mail & Telephone Surveys, Wiley-Interscience, 1978. Peter H. Rossi, James D. Wright, Andy B. Anderson, Handbook of Survey Research, Academic Press, 1983. Seymour Sudman & Norman M. Bradburn, Asking Questions, Jossey-Bass, 1982. Robert M. Groves & Robert L. Kahn, Surveys by Telephone, Academic Press, 1979. Norman M. Bradburn & Seymour Sudman, Polls & Surveys, Jossey-Bass, 1988. Jean M. Converse, Survey Research in the United States, University of California Press, 1987. Hubert O'Gorman, ed., Surveying Social Life, Wesleyan University Press, 1988. Herbert H. Hyman, Taking Society's Measure, Russell Sage Foundation, 1991. Judith M. Tanur, ed., Questions About Questions, Russell Sage Foundation, 1992. 218.syllabus.F’09 CHS / Epi M218 Fall 2009 Page 2 D. Supplementary Materials The course web site has links for these articles. http://www.ccle.ucla.edu/ You will need to use your UCLA BOL log-in to enter the UCLA Moodle site. Only students registered for the class will be able to access course material. Remember that the articles are under copyright. Articles on the Web Site: 1. American Association for Public Opinion Research, Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys, RDD Telephone Surveys, In-Person Household Surveys, and Mail Surveys of Specifically Named Persons, 2000. 2. Barton, AH. “Asking the Embarrassing Question,” The Public Opinion Quarterly 22: 6768, 1958. 3. Bhopal, Raj & Liam Donaldson, “White, European, Western, Caucasian, or What? Inappropriate Labeling in Research on Race, Ethnicity, and Health,” American Journal of Public Health 88(9):1303-1307, 1998. 4. Binson, D., J.A. Canchola, J.A. Catania, “Random Selection in a National Telephone Survey: A Comparison of the Kish, Next-Birthday, and Last-Birthday Methods,” Journal of Official Statistics 16(1):53-59, 2000. 5. Bischoping, K., J. Dykema, “Toward a Social Psychological Programme for Improving Focus Group Methods of Developing Questionnaires,” Journal of Official Statistics 15(4):495-516, 1999. 6. Blair, E.A., G.K. Ganesh, “Characteristics of Interval-based Estimates of Autobiographical Frequencies,” Applied Cognitive Psychology 5:237-250, 1991 7. Bourque, L.B. “Coding.” In M.S. Lewis-Beck, A. Bryman, T.F. Liao, Editions, The Sage Encyclopedia of Social Science Research Methods, Volume 1, Thousand Oaks, Ca: Sage Publications, 2003, pp. 132-136. 8. Bourque, L.B. “Coding Frame.” In M.S. Lewis-Beck, A. Bryman, T.F. Liao, Editions, The Sage Encyclopedia of Social Science Research Methods, Volume 1, Thousand Oaks, Ca: Sage Publications, 2003, pp. 136-137. 218.syllabus.F’09 CHS / Epi M218 Fall 2009 Page 3 9. Bourque, L.B. “Cross-Sectional Design.” In M.S. Lewis-Beck, A. Bryman, T.F. Liao, Editions, The Sage Encyclopedia of Social Science Research Methods, Volume 1, Thousand Oaks, Ca: Sage Publications, 2003, pp. 229-230. 10. Bourque, L.B. “Self-Administered Questionnaire.” In M.S. Lewis-Beck, A. Bryman, T.F. Liao, Editions, The Sage Encyclopedia of Social Science Research Methods, Volume 3, Thousand Oaks, Ca: Sage Publications, 2003, pp. 1012-1013. 11. Bourque, L.B. “Transformations.” In M.S. Lewis-Beck, A. Bryman, T.F. Liao, Editions, The Sage Encyclopedia of Social Science Research Methods, Volume 3, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2003, pp. 1137-1138. 12. Norman Bradburn, The Seventh Morris Hansen Lecture on “The Future of Federal Statistics in the Information Age,” with commentary by TerriAnn Lowenthal, Journal of Official Statistics 15(3):351-372, 1999. 13. Bradburn, N.M. “Understanding the Question-Answer Process,” Survey Methodology 30:5-15, 2004. 14. Bradburn, N.M., L.J. Rips, S.K. Shevell, “Answering Autobiographical Questions: The Impact of Memory and Inference on Surveys,” Science 236:157-161, 1987. 15. Brick, J.M., J. Waksberg, S. Keeter, “Using Data on Interruptions in Telephone Service as Coverage Adjustments,” Survey Methodology 22(2):185-197, 1996. 16. Caplow, T., H.M. Bahr, V.R.A. Call. “The Polls--Trends, The Middletown Replications: 75 Years of Change in Adolescent Attitudes, 1924-1999,” Public Opinion Quarterly 68:287-313, 2004. 17. Christian, L.M., D.A. Dillman. “The Influence of Graphical and Symbolic Language Manipulations on Response to Self-Administered Questions,” Public Opinion Quarterly 68:57-80, 2004. 18. Conrad, FG, MF Schober. “Promoting Uniform Question Understanding in Today’s and Tomorrow’s Surveys,” Journal of Official Statistics 21: 215-231, 2005. 19. Converse, Philip E. & Michael W. Traugott, “Assessing the Accuracy of Polls & Surveys,” Science 234:1094-1098, November 28, 1986. 20. Couper, M.P., “Survey Introductions and Data Quality,” Public Opinion Quarterly 61:317-338, 1997. 21. Couper, Mick P., Johnny Blair & Timothy Triplett, “A Comparison of Mail & E-mail for a Survey of Employees in U.S. Statistical Agencies,” Journal of Official Statistics 15(1):39-56, 1999. 22. Couper, Mick P., “Web Surveys: A Review of Issues and Approaches,” Public Opinion 218.syllabus.F’09 CHS / Epi M218 Fall 2009 Page 4 Quarterly 64:464-494, 2000. 23. Couper, M.P., R. Tourangeau. “Picture This! Exploring Visual Effects in Web Surveys,” Public Opinion Quarterly 68:255-266, 2004. 24. Curtin, R, S Presser, E Singer. “Changes in Telephone Survey Nonresponse Over the Past Quarter Century,” Public Opinion Quarterly 69:87-98, 2005. 25. de Leeuw, ED. “To Mix or Not to Mix Data Collection Modes in Surveys,” Journal of Official Statistics 21: 233-255, 2005. 26. Dengler, R., H. Roberts, L. Rushton, “Lifestyle Surveys--The Complete Answer?” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 51:46-51, 1997. 27. Dillman, DA, A Gertseva, T Mahon-Haft. “Achieving Usability in Establishment Surveys Through the Application of Visual Design Principles,” Journal of Official Statistics 21: 183-214, 2005. 28. Dykema, Jennifer, Nora Cate Schaeffer. “Events, Instruments, and Reporting Errors,” American Sociological Review 65:619-629, 2000. 29. Frankenberg, E, NR Jones. “Self-Rated Health and Mortality: Does the Relationship Extend to a Low Income Setting?” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 45: 441-452, 2004. 30. Fricker, S, M Galesic, R Tourangeau, T Yan. “An Experimental Comparison of Web and Telephone Surveys,” Public Opinion Quarterly 69:370-392, 2005. 31. Fullilove, Mindy Thompson, “Comment: Abandoning 'Race' as a Variable in Public Health Research--An Idea Whose Time Has Come,” American Journal of Public Health 88(9): 1297-1298, 1998. 32. Gardner, W., B.L. Wilcox, “Political Intervention in Scientific Peer Review,” American Psychologist 48:972-983, 1993. 33. Gaziano, C. “Comparative Analysis of Within-Household Respondent Selection Techniques,” Public Opinion Quarterly 69:124-157, 2005. 34. Groves, R.M., M.P. Couper, “Contact-Level Influences on Cooperation in Face-to-Face Surveys,” Journal of Official Statistics 12(1):63-83, 1996. 35. Krosnick, Jon A., Allyson L. Holbrook, Matthew K. Berent, Richard T. Carson, W. Michael Hanemann, Raymond J. Kopp, Robert Cameron Mitchell, Stanley Presser, Paul 218.syllabus.F’09 CHS / Epi M218 Fall 2009 Page 5 A. Ruud, V. Kerry Smith, Windy R. Moody, Melanie C. Green, Michael Conaway, “The Impact of ‘No Opinion’ Response Options on Data Quality, Non-Attitude Reduction or an Invitation to Satisfice?” Public Opinion Quarterly 66:371-403, 2002. 36. Kornhauser, Arthur, and Paul B. Sheatsley, “Questionnaire Construction and Interview Procedure,” Appendix B, in Claire Selltiz, Lawrence S. Wrightsman, Stuart W. Cook (eds.), Research Methods in Social Relations, 3rd Edition, Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1976, pp. 541-573. 37. Krosnick, Jon A., “Survey Research,” Annual Review of Psychology 50:537-67, 1999. 38. Lavin, Daniele, Douglas W. Maynard. “Standardization vs. Rapport: Respondent Laughter and Interviewer Reaction During Telephone Surveys,” American Sociological Review 66:453-479, 2001. 39. Macera, Caroline, Sandra Ham, Deborah A. Jones, Dexter Kinsey, Barbara Ainsworth, Linda J. Neff. “Limitations on the Use of a Single Screening Question to Measure Sedentary Behavior,” American Journal of Public Health 91:2010-2012, 2001. 40. Martin, E., T.J. DeMaio, P.C. Campanelli, “Context Effects for Census Measures of Race and Hispanic Origin,” Public Opinion Quarterly 54:551-566, 1990. 41. Mokdad, Ali H., Donna F. Stroup, Wayne H. Giles, “Public Health Surveillance for Behavioral Risk Factors in a Changing Environment, Recommendations from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Team,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 52 (RR-9), Centers for Disease Control, May 23, 2003. 42. Olsen, Jørn on behalf of the IEA European Questionnaire Group, “Epidemiology Deserves Better Questionnaires,” International Journal of Epidemiology 27:935, 1998. 43. Presser, S., M.P. Couper, J.T. Lessler, E. Martin, J. Martin, J.M. Rothgeb, E. Singer, “Methods for Testing and Evaluating Survey Questions,” Public Opinion Quarterly 68:109-130, 2004. 44. Rizzo, L., J. M. Brick, I. Park, “A Minimally Intrusive Method for Sampling Persons in Random Digit Dial Surveys,” Public Opinion Quarterly 68:267-274, 2004. 45. Scheuren F, American Statistical A. What is a Survey?: American Statistical Association; 2004.. 46. Shaeffer, EM, JA Krosnick. GE Langer, DM Merkle. “Comparing the Quality of Data Obtained by Minimally Balanced and Fully Balanced Attitude Questions,” Public Opinion Quarterly 69: 417-428, 2005. 47. Sigelman, L, S.A. Tuck, JK Martin. “What’s In a Name? Preference for ‘Black’ Versus ‘African-American’ Among Americans of African Descent,” Public Opinion Quarterly 69: 429-438, 2005. 218.syllabus.F’09 CHS / Epi M218 Fall 2009 Page 6 48. Stevens, Gillian & David L. Featherman, “A Revised Socioeconomic Index of Occupational Status,” Social Science Research 10:364-395, 1981. 49. Stevens, Gillian & Joo Hyun Cho, “Socioeconomic Indexes and the New 1980 Census Occupational Classification Scheme,” Social Science Research 14:142-168, 1985. 50. Suchman, L., B. Jordan, “Interactional Troubles in Face-to-Face Survey Interviews,” Journal of the American Statistical Association 85(409):232-253, 1990, with Commentary by Stephen E. Fienberg, Mary Grace Kovar and Patricia Royston, Emanuel A. Schegloff, and Roger Tourangeau, and Rejoinder by Lucy Suchman and Brigitte Jordan. 51. Tambor, E.S., G.A. Chase, R.R. Faden et al, “Improving Response Rates Through Incentive and Follow-up: The Effect on a Survey of Physicians' Knowledge of Genetics,” American Journal of Public Health 83:1599-1603, 1993. 52. Todorov, A., C. Kirchner, “Bias in Proxies’ Reports of Disability: Data from the National Health Interview Survey on Disability,” American Journal of Public Health 90(8):12481253, 2000. 53. Wang, J.J., P. Mitchell, W. Smith, “Vision and Low Self-Rated Health: The Blue Mountains Eye Study,” Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science 41(1):49-54, 2000. 54. Willis, G.B., P. Royston, D. Bercini, “The Use of Verbal Report Methods in the Development and Testing of Survey Questionnaires,” Applied Cognitive Psychology 5:251-267, 1991. 218.syllabus.F’09 CHS / Epi M218 Fall 2009 Page 7 Course Materials Available on Course Web Site http://www.ccle.ucla.edu/: Consent form materials 1. OPRR Reports, Protection of Human Subjects, Title 45, Code of Federal Regulations, Part 46, Revised June 18, 1991, Reprinted March 15, 1994. 2. Siegel, Judith, Linda Bourque, Example of Submission, Questions Raised by the IRB and Responses, 2002. ISSR materials Engelhart, Rita, “The Kish Selection Procedure” Codebooks Example of a Codebook, December 1, 2002. Also on earthquake web site: http://www.sscnet.ucla.edu/issr/da/earthquake/erthqkstudies2.index.htm Scale & index construction 1. Inkelas, Moira, Laurie A. Loux, Linda B. Bourque, Mel Widawski, Loc H. Nguyen, “Dimensionality and Reliability of the Civilian Mississippi Scale for PTSD in a Postearthquake Community,” Journal of Traumatic Stress 13, 149167, 2000. 2. McKennel, A.C., Chapter 7, “Attitude Scale Construction,” in C.A. O'Muircheataugh & C. Payne (eds.), Exploring Data Structures, Vol. 1, The Analysis of Survey Data, John Wiley & Sons, 1977, pp. 183-220. 3. Bourque, L.B, H. Shen. “Psychometric Characteristics of Spanish and English Versions of the Civilian Mississippi Scale,” Journal of Traumatic Stress 2005; 18:719-728. Materials related to the administration and analysis of survey data 1. Questionnaire for Assignment #1 2. Record for Non-respondents 3. Enlistment Letters 4. Call Record 5. Formatting Questionnaires 218.syllabus.F’09 CHS / Epi M218 Fall 2009 Page 8 6. Income Questions 7. Calculating Response Rates 8. Examples of Grids 9. Codebook and Specifications 10. Constructing a Code Frame 11. Scale Construction Example Questionnaires, Specifications and Codebooks are also available at: http://www.sscnet.ucla.edu/issr/da/earthquake/erthqkstudies2.index.htm and http://www.ph.ucla.edu/sciprc/3_projects.htm under Disasters. The books and articles listed above will give you a background on and an introduction to surveys and questionnaires. Each book has different strengths and weaknesses. They should be considered resources. The required books are available in the Health Sciences Bookstore. The Recommended books are available in the various UCLA libraries. The decision as to which books you buy and the order in which you read them is yours. I recommend reading all the material you buy or check out as soon as possible. It will then be available to you as a resource as we go through the quarter. COURSE REQUIREMENTS AND GRADING Subjects and Site: Each student selects a topic on which s/he wants to design questionnaires, and the site(s) at which s/he will conduct the interviews needed in pretesting the questionnaire. You are free to select any site and any sample of persons with the following exceptions: 1. All respondents MUST be at least 18 years of age. 2. DO NOT collect information from respondents such as name, address, and phone number which would enable them to be identified. 3. DO NOT interview persons in the Center for Health Sciences or persons connected with the Center for Health Sciences. 4. DO NOT interview your fellow students, your roommates, your friends, your relatives, or persons with whom you interact within another role (e.g., employees, patients). 5. DO NOT ask about topics which would require the administration of a formal Human Consent Form. 218.syllabus.F’09 CHS / Epi M218 Fall 2009 Page 9 Should you violate these requirements, the data collected will not fulfill the requirements for an assignment in this class. Only interviews, not self-administered questionnaires, can be used for pretesting the questionnaires developed in this class. Course Objectives and Assignments: The objective of this course is to learn how to design respectable questionnaires. Research data can be collected in many ways. Questionnaires represent one way data is collected. Although usually found in descriptive, cross-sectional surveys, questionnaires can be used in almost any kind of research setting. Questionnaires can be administered in different ways and the questions within a particular questionnaire can assume an infinite variety of formats. As is true of any research endeavor, there are no absolutes in questionnaire design. There are no recipes and no cookbooks. The context of the research problem you set for yourself will determine the variety of questionnaire strategies that are appropriate in trying to reach your research objective; the context will not tell you the absolutely “right” way to do it. The final “product” for the quarter is a questionnaire designed in segments and pretested at least three times. The questionnaire will be designed to collect data to test a research objective specified by you during the second week of the quarter. The final version of the questionnaire is due Wednesday, December 9th at 5:00 PM. All assignments must be typed; handwritten materials are not accepted. Every version of your questionnaire must be typed, but final versions should be as close to “picture-ready” copy as you can manage. For Assignment 5, due on December 9th, you will provide the final copy of your questionnaire, a full copy of Interviewer/Administrator Specifications, a Codebook and/or coding instructions, a summary of data collected in your last pretest, a tentative protocol that could be used to analyze data collected with your questionnaire, and what, if anything, further you would like to do if time allowed. The following five assignments will move you toward the final product. ASSIGNMENTS Assignment 1: Practice Interviewing (5% of Final Grade) Due October 5 This assignment is designed to expose you to the process of interviewing. Questionnaires will be handed out on the first day of class (September 28th). You are to conduct 9 interviews. On October 5, turn in both the completed interviews and a brief write-up describing where you went, what happened and a brief description of the data you collected. These materials are also on the course web site http://www.ccle.ucla.edu/. In selecting respondents, go to a central public location such as a shopping area, the beach, or a park. In conducting your interviews, try to obtain a range of ages, sexes, and ethnic groups. You will be given identification letters to carry in case anybody asks who you are. DO NOT INTERVIEW ON PRIVATE PROPERTY UNLESS YOU HAVE PERMISSION. 218.syllabus.F’09 CHS / Epi M218 Fall 2009 Page 10 THIS AFFECTS MANY SHOPPING CENTERS. Keep track of the characteristics of refusals on the “Record for Non-respondents.” A refusal is a person you approach for an interview who turns you down. Assignment 2: Statement of Your Research Question (5% of Final Grade) Due October 7th Questionnaires are designed to get data that can be used to answer a research question. To help you get started, state a research question. Remember it should be relevant to the interviewing sites available to this class. Is your research question, as written, testable? What concepts are included in or implied by your question? Can your concepts be operationalized into working definitions and variables for which a questionnaire is a viable data collection procedure? Assignment 3: “Mini-Questionnaire” #1. (25% of Final Grade) Due October 21th Part 1 Prepare and test “Mini-Questionnaire” #1. This represents your first attempt at designing a questionnaire to test your “Research Question.” The substantive content of the questionnaire should focus on current status, behaviors or knowledge. You can choose any topic that interests you, but since our focus is on “health,” you may want to consider asking about: 1) Current acute and chronic diseases, accidents, injuries, disabilities, and impairments; and 2) Knowledge and use of health services. In addition to substantive content, all questionnaires must collect demographic information on such things as: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Respondent age Respondent education Individual, family or household income Occupation Respondent marital status There is no limit to the number of questions you may include. However, you must provide a minimum of 6 questions in addition to the demographic questions discussed above. I expect your questionnaire to include a mixture of open-ended and closed-ended questions. Open-ended questions are particularly useful when you are in the process of exploring an area of research or in the initial stages of designing a questionnaire. In preparing the questions in your questionnaire, keep in mind the problems of survey research design which have been discussed in class and in the readings. Pay particular attention to the following: 1. Respondent frame of reference--will it be the same as yours? 218.syllabus.F’09 CHS / Epi M218 Fall 2009 Page 11 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. Level of concreteness/abstraction. Question referent--is it clear, and is it what you intend? Tone of question--will it stimulate yea-saying? Balance--within the question and in the set of questions. Problems of bias induced by wording--watch out for leading, loaded terms, etc. Screening questions to reduce noise due to non-attitudes. Indicate explicitly the format of the questions. How will it look? Present the questions in the order you want them to appear in the questionnaire. Pay particular attention to the following: 1. 2. 3. 4. Problems of preservation due to fatigue. Problems of bias induced by contamination of response due to ordering of questions. Problems of threatening material/invasion of privacy. Skip patterns to tailor questionnaire for various respondent types. In sum, your questionnaire should look as much as possible like a finished product, ready to be fielded or at least pre-tested. Part 2 In addition to your questionnaire you must provide a justification for each question. This is the beginning of writing Specifications. For each question or set of related questions there should be a brief statement as to why the question is included/necessary, and the rationale behind the format selected. IT IS NOT SUFFICIENT TO SAY “IT'S SELF-EVIDENT.” It is NEVER self-evident to someone else--like me! Specifications should also include the research question being tested and information about how your sample was selected and from where. Part 3 Test your questionnaire by interviewing a convenience sample of at least five respondents. Part 4 You must also complete two applications for Human Subjects Protection specific to an “Application for the Involvement of Human Participants in Social Behavioral and Educational Research (SBER) and Health Services Research (HSR).” The forms are new this year which may result in all of us being confused about how best to work with them. Go to http://www.oprs.ucla.edu/. Click on “Forms,”(http://www.oprs.ucla.edu/human/forms/). Click on Application for Social Behavioral & Educational Research (SBER) & Health Services Research (HSR). This gives you HS-1, Application for the involvement of Human Participants in Social Behavioral and Educational Research (SBER) and Health Services Research (HSR). This is the first form that you must complete; we sometimes call it the long form. Now go to http://www.oprs.ucla.edu/human/forms/exempt-certifications. Click on Exempt Categories. Read through the categories so that you understand them. Then click on Certification of Exemption Form â “ Categories 1, 2, 3, 5 and 6. This takes you to the second form that you must fill out “Application for Certification of Exemption from IRB Review for 218.syllabus.F’09 CHS / Epi M218 Fall 2009 Page 12 Exemption Categories 1, 2, 3, 5, and 6.” Further Information About the Protection of Human Subjects If you are currently involved in any research activities, as a UCLA student you must be certified. That process is also new this year. If you were certified in the past and did NOT complete the new certification process by September 1, 2009, you cannot be involved in any UCLA research projects that involve human subjects until you are certified. To find out about and complete the certification process, go to http://www.oprs.ucla.edu/human/certification. REMEMBER! All research that involves human subjects that is conducted by UCLA faculty, staff or students MUST be cleared by the Office for the Protection of Human Subjects (OPRS). On October 21th, turn in: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. All the completed interviews you did. A copy of your Human Subjects materials: HS-1 which is required for the full consent process; and the Exemption Form as if you qualified for and were requesting an exemption. A copy of your specifications. One copy of the blank questionnaire for me. Fifteen copies of the blank questionnaire; these are to share with your classmates. A brief report (5-7 typed pages) describing the instrument you constructed, the data collected with it, the respondents from whom the data was collected, what you think worked well and what you think did not, and how you would change it. Assignment 4: “Mini-Questionnaire” #2. (25% of Final Grade) Due Novermber 18th Revise the questionnaire you designed in Assignment 3 in accordance with your accrued wisdom and the succinct observations from me and your classmates. Add a new set of questions that collects at least one of the following: sensitive behaviors, retrospective data, or attitudes and opinions. For example, you might design questions that will elicit information about substance abuse (e.g., use of alcohol), the use of non-traditional health practices (e.g., faith healers, curanderos, over-the-counter drugs, other people's drugs, etc.), threatening behaviors (e.g., abortion, etc.). Retrospective data might be collected about past health care experienced by the respondent over his/her lifetime. Finally, you might find out the respondents' opinions of their current or past health care. If you have a good reason, you could adopt or adapt sets of questions from other studies if they help you get to your objective. Explicitly indicate the format of the questions. Will there be a checklist? How should it look if presented to the respondent? Do you need a card to cue the respondent? What should be on the card? Are other visual aids needed? Start designing a codebook that can be used with your questionnaire. The codebook should include information on how verbal answers are converted to numbers, where the variables 218.syllabus.F’09 CHS / Epi M218 Fall 2009 Page 13 are located, and what the variables are named. I recommend using your questionnaire as the basis for your codebook. Whenever you write a question, you should have in mind the probable responses--if you cannot think of the responses, then you have not thought about the question enough!! The process of setting up categories for expected (and finally actual) responses is called code construction. Closed-ended, pre-coded questions have already had codes constructed for them; the respondent is presented with a specified set of alternatives which are the codes used later in data analysis. The only additional coding problem presented by pre-codes is how to handle residuals. For the code construction assignment, you must consider each of your pre-coded questions, assign numbers to the alternatives following the procedures outlined in class discussions and readings, and solve the residual problem. For open-ended questions, you have to consider all possible responses and list these along with code numbers. Include instructions for the coder to follow regarding how many responses are to be coded, any precedence rules to follow and any other problems you think might arise. Remember in this case also to provide a way of handling residual categories. Remember to include codes for the required questions on age, education, income and marital status. Do not attempt to set up a code for occupation; do write a paragraph outlining your thoughts about how one would go about coding occupational data. You do not have to write specifications for this assignment. You may want to start revising your old ones and writing new ones in anticipation of Assignment 5. Test your questionnaire by interviewing at least five respondents. On November 18h, turn in: 1. A report (7-10 typed pages) describing the development of the instrument--why items were selected, how and why they were revised; the data collected with this instrument; the sample of respondents from whom the data were collected. 2. Sixteen copies of the blank questionnaire; one for me and 15 to share with your classmates. 3. The codebook. 218.syllabus.F’09 CHS / Epi M218 Fall 2009 Page 14 Assignment 5: Your Magnum Opus! (40% of the final grade) Due December 9th by 5:00 PM This is the culmination of all your work! Revise your earlier questionnaires consistent with your vastly increased wisdom. Remember that you should have a “final product” that is as close to “picture-ready copy” as you can manage. This questionnaire should include variable names for coding. Turned in with the questionnaire are a final set of Specifications and a final Codebook, along with a write-up that summarizes your pretest interviews of this version of the questionnaire with 8-10 respondents, a proposed analysis plan, and discussion of any further changes that might be considered were you to actually use this instrument in a study. On December 9th, turn in: 1. A 7-10 page report that summarizes your pretest interviews, a proposed analysis plan, and a discussion of any further changes that should be considered were you to actually use this instrument in a study. 2. One blank questionnaire. 3. One set of final specifications. 4. One final codebook. GENERAL STATEMENTS ON GRADING AND PRESENTATION OF ASSIGNMENTS When you enter M218, it is assumed that you will exit with a grade of “B.” A “B” is a good, respectable grade. I write lots of letters of recommendation for people who get “B’s” in M218. An “A” grade is earned by doing a really exceptional job. If you end up with a “C” grade, it probably will be because you did not make a serious effort in this class: you did not do the reading, you never came to class, you left all the assignments for the night before, etc. In other words, it is hard to get a “C” in this class, BUT if that is what you earn, then that is what you will get. It is expected that all assignments will be turned in on the date due. There are no extensions. Incompletes are not given in this course. 218.syllabus.F’09 CHS / Epi M218 Fall 2009 Page 15 CLASS SCHEDULE WEEK/DATE, ASSIGNMENTS TOPIC, RELEVANT READINGS WEEK 1: CONTEXT OF THE QUESTIONNAIRE 1. Study Objective 2. Sample and Unit of Analysis 3. Types of Data to be Collected 4. Surveys 5. Funding Services: Contracts and Grants September 28 Relevant Readings: Aday, Chapters 1-5, 6-7; Bourque & Fielder, Chapters 1, 5; Bourque in Lewis Beck, Bryman, Liao, pp. 229-230. September 30 STARTING A RESEARCH STUDY 1. Study Objective 2. Research Questions 3. Hypotheses, Concepts, and Working Definitions 4. Variables: Independent, dependent, control 5. Levels of Measurement Relevant Readings: Aday, Chapters 1-5; Bourque & Fielder, Chapter 1. WEEK 2: October 5 ASSIGNMENT 1 DUE TYPES OF QUESTIONNAIRES 1. Administrative Types 2. Question Types: Open/Closed 3. Information Obtainable by Questionnaire: Facts, Behaviors, Attitudes Relevant Readings: Aday, Chapters 1-5; Bourque & Fielder, Chapter 1; Curin, Presser, Singer; Fricker et al. October 7 ASSIGNMENT 2 DUE HUMAN SUBJECTS PROTECTION AND FORMS Download the HS-1 form, the Exemption form, and the list of Exemption categories before class from either the web site or http://www.oprs.ucla.edu/. See instructions on pages 11-12. Relevant Readings: OPRS web site and materials on web site. 218.syllabus.F’09 CHS / Epi M218 Fall 2009 Page 16 WEEK 3: October 12 QUESTIONS TO OBTAIN DEMOGRAPHIC INFORMATION 1. Why? 2. How much? 3. How? 4. Location? 5. Household Roster 6. Selecting Questions from Other Studies Relevant Readings: Aday, Chapters 8, 10; Bourque & Fielder, Chapters 2, 3; Sigelman, Tuck, Martin; examples on course web site and earthquake web site. October 14 “BEGINNINGS” AND “ENDS” OF QUESTIONNAIRES 1. Call Record Sheet 2. Enlistment Letters 3. Questions to Interviewer Relevant Readings: Bourque & Fielder, Chapter 6; examples on websites. WEEK 4: October 19 & 21 QUESTIONNAIRE SPECIFICATIONS 1. Functions 2. Format Relevant Readings: Bourque and Fielder, Chapter 3. ASSIGNMENT 3 DUE October 21 WEEK 5: October 26 ASCERTAINING INFORMATION ABOUT RETROSPECTIVE BEHAVIORS 1. Grids 2. Histories 3. Aided Recall 4. Use of Records Relevant Readings: Aday, Chapter 11; 218.syllabus.F’09 CHS / Epi M218 Fall 2009 Page 17 WEEK 5, continued October 28 ASCERTAINING INFORMATION ABOUT THREATENING BEHAVIORS 1. Approaches 2. Closed vs. Open 3. Using Informants 4. Location 5. Validation Relevant Readings: Barton. WEEK 6: November 2 & 4 CODEBOOKS AND CODE CONSTRUCTION 1. Objective 2. Types 3. Content Analysis Relevant Readings: Aday, Chapter 13; Bourque & Fielder, Chapter 3; Bourque and Clark; Bourque, Coding, Code Frames; examples on web sites. WEEK 7: November 9 APHA FORMATTING QUESTIONNAIRES 1. Order/Location 2. Grouping 3. Spacing Relevant Readings: Aday, Chapter 12; Bourque & Fielder, Chapter 4; Couper, Tourangeau; Krosnick et al; Shaeffer et al. November 11 218.syllabus.F’09 Veterans Day HOLIDAY CHS / Epi M218 Fall 2009 Page 18 WEEK 8: November 16 & 18 MEASURING ATTITUDES 1. Beginning 2. Developing Composite Measures 3. Use of Existent Measures Relevant Readings: Aday, Chapter 11; examples on websites. ASSIGNMENT 4 DUE November 18th WEEK 9: November 23 & 25 MEASURING ATTITUDES, CONTINUED 1. Reliability 2. Validity WEEK 10: November 30 DATA PROCESSING AND ANALYSIS OF QUESTIONNAIRE DATA 1. Raw Data vs. Processed File 2. Coding 3. Data Entry/Keypunching 4. Cleaning 5. Raw vs. Actual Variables 6. Data Quality, Missing Data, etc. Relevant Readings: Aday, Chapters 14, 15; Bourque & Fielder, Chapter 6. December 2 ADMINISTRATION OF SURVEYS Relevant Readings: Aday, Chapter 13; Bourque & Fielder, Chapter 6. WEEK 11: December 9 218.syllabus.F’09 ASSIGNMENT 5 DUE AT 5:00 PM