Guidelines on the Setting of Targets, Evaluation

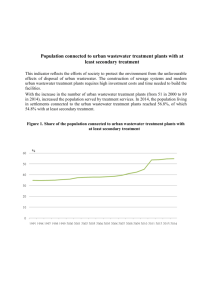

advertisement