Company Law - Lecture Notes

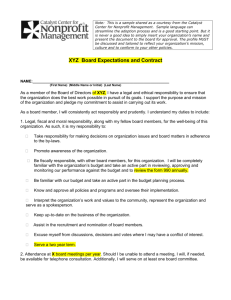

advertisement