An African Novel as Oral Narrative Performance

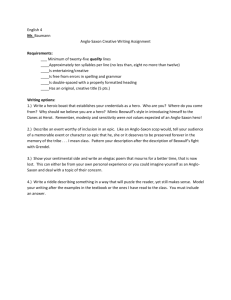

advertisement