Ethical Theories Humanitarian Aid - St. Olaf Pages

advertisement

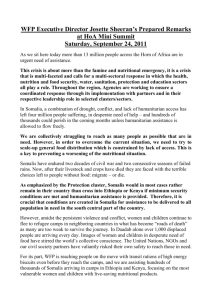

Sara Ryan and Moira Wood Professor Gervais Global Health Ethics 12 March 2012 Ethical Theories for Humanitarian Aid For the layman, ethical decisions are based on internal moral principles, and very rarely employ the abundant complicated theories that philosophers and ethicist have defined to aid the populous through these seemingly impossible ethical decisions. Some of these theories include Utilitarian, Contractualism, Denatological, Covenantalsim, and Discorse Ethics; all of which are pioneered by some of the most significant philosophers who have contributed to the complex moral society that exists today. To further understand these intricate ethical theories, they will be explored within the context of global Humanitarian Aid with the example of famine relief in Somalia. It is difficult to compare which ethical theory works better when they are not attempting to accomplish the same goals determined on predicted consequences and which of those consequences are worse comparatively. This is one reason why a combination of these theories may be more applicable than only employing one or the other. Utilitarianism is based on the principle of do the greatest good for the greatest number (Hutchings, 30). This rationalist theory begins by defining “good” since its meaning is not universal. Good can be defined in terms of pain and pleasure since, “every human being is essentially the same (driven by the desire for pleasure and the fear of pain),” good defined as, without pain or death, and pleasure including the basic needs of life (Hutchings, 31). It is imperative that we point out that each human life is equal, “to act morally” according to Bentham, “is to act impartially” giving utilitarianism an egalitarian perspective (Hutchings, 30). Singer and Hardin use two different perspectives that show the greatest good for the greatest number does not always boil down to the same solution. Singer believes everyone is equally responsible for the evils in the world, and aiding others should create a marginal utility (Singer, 5). The line is drawn when aid diverts funds from the people helping and henceforth creates a larger deprivation (Singer, 2). His argument does not discriminate against neighbors near and far due to the globalization of today and the equality of human life (Singer, 4). On the same scale but from another angle Hardin realizes there are situations when not all may be helped without jeopardizing the greatest good for the greatest number. There is a point where the line must be drawn in order to avoid absurdity (Harding, 26). A world full of sinful and unjust human beings, without a global government controlling resources, there is no possible way to create a marginal utility as Singer hopped for (Hardin, 26). In order to address the famine in Somalia using the Utilitarian approach, the greatest good for the greatest number, must be first be defined in terms of “good or bad.” Both Singer and Hardin must be taken into consideration. Singer clearly states that if everyone did their part then Somalia would have enough aid and the personal impact on each donor would be minimal. The problem is all people do not have the same moral regiment, and unless enforced by law, not everyone will give aid and therefore not complete the goal. Singer would agree that starving is bad and it is everyone’s responsibility to prevent starvation when possible until a marginal utility is created. If everyone gave as much food or money as they were able, then the famine in Somalia would not be a death sentence for a great number of people. Hardin on the other hand would look at the famine in Somalia and realize that creating a marginal utility would be a greater harm to those aiding than those currently suffering, due to economic changes and decreased quality of life for those giving aid. Even keeping the marginal utility in mind, harm would follow when aid is provided due to the space needed for protection. Famine is caused due to societal instability, according to O’Neill, if a marginal utility is reached no one will be able to aid in the future. In the case of humanitarian aid Hardin would refuse aid to Somalia because the consequence would lead to a far greater tragedy and therefor not fulfill the greatest good for the greatest number principle of utilitarianism (O’Neill, 142). Contractualisim and Harding’s Utilitarianism can be used in conjunction with each other when an elimination of some of the population is the only way to achieve the greatest good for the greatest number. Contractualisim involves a mutual agreement between people on an ethical basis for handling situations. A mutual agreement based on people living without “social, legal, or political authority and organization” describes the social contract in a state of nature (Hutchings, 33). This is viable because “individuals in the state of nature contract with each other to trade off their individual natural rights to pursue their own self-preservation by all available means” (Hutchings, 34). This theory is heavily influenced by justice, behind a veil of ignorance. The veil of ignorance allows for ethical decisions based on fairness when the participants do not know what their personal stake will be, but having the same consequence no matter what. A veil of ignorance would include fundamental rights provided to all human beings. Deciding which of those fundamental rights and freedoms to include is another argument all together. Rawls, and others, following the contractualist theory would agree that there needs to be a universal law in which all are responsible to abide by. In the case of humanitarian aid people are required to give up some freedoms in order to obtain enough order to survive. This can be applied in a governmental position raising taxes to fund humanitarian aid. Individuals earning money are forced to give “obligated charity” in order to fulfill the ethical value that all human life is valuable. As defined by contractualists we must agree with one another to give up the rights of a capitalist nation in order to prevent a state of nature. This example would also use the veil of ignorance to ensure moral fairness. Those making the decisions to raise taxes must do so without knowing how much money of theirs will be forfeited as well as see themselves as the ones in need of aid from others. Covenantlaism stems from the Christan tradition based on the covenant the the devote followers of Jesus Christ make with God, as well as with their neighbors. As Professor Edward Langerak of St Olaf College explains, “Christians believe that the imaging God involves our being created in essential relationship with God, with our own selves, with other persons, and with the rest of creation” (Langerak, 8). In this, God’s disciples act out of gratitude from God’s ultimate gift of life and creation, and it is through this gift that cannot be reciprocated, those in covenant with God are perpetually indebted to him, and therefore also act out of a certain sense of obligation. This covenant becomes identity forming and defining, and harbors an obligation to the world in those who believe. It is due to this identity-shaping component of covenants, that they “tend to endure over time and are influenced by new developments in unspecified and openended ways” (Langerak, 9). While this does allow for its adaptability across time and space, making it almost immortal, but because this set of ethical principle are grounded in a relationship with God, as opposed to reason, it becomes more difficult to grasp. Moreover, in this covenant with God, you are also in covenant with all of Gods’ creation, and therefore have a Samaritan duty of all people. This would mandate that all of God’s children give up all superfluous things and live a good, simple life to help those in need. This same sentiment is expressed in regard to humanitarian aid as discussed previously by Singer, “we are morally required to give to famine relief at least up to the amount we currently spend on consumer ‘trivia’ and potentially up to the point of ‘marginal utility’, at which the utility of the victims of famine and the givers of relief has been roughly equalized” (Hutchings, 85). As a utilitarian, Singer is grounded in moral reason as opposed to the dependence of the covenant with God as Covenantalist depend. So to apply this theory to humanitarian aid, and grant relief to those suffering form famine in Somalia, Covenantalsit would view those suffering as neighbors and sharing covenant, and therefore they would feel obliged to grant aid up to the point of living a simple life in Gods image. This become problematic, however, is that a Covenantalist has no limit on who is a neighbor, and therefore they would have to grant aid to all in need, and this is a impossible task, as the need is too great. It is also unreasonable to assume that all those who are able would grant aid, because not all believe themselves to be in covenant with God. This creates a small population upon witch all aid is dependant, and therefore not a sustainable or even attainable form of humanitarian aid. Kant uses the categorical imperative to define a strategy the Deontological theory uses. In order to avoid falling into the Covenantlaism realm, reason must be a basis for the categorical imperative rather than faith. The categorical imperative has two parts to it: first, “act only on maxims that one can consistently will to become universal law” and “never treat other solely as means but always also as ends-in-themselves” (Hutchings, 41). Acting on maxims is being able to set a moral and apply it as an always. If the maxim still ought to be acted on then it becomes universal. The categorical imperative is being able to put aside what may seem moral from individual feelings, perspectives, identities, and interests (Hutchings, 41). Treating all people as an end-in-themselves, there is a respect for the value of humanity and the ability for humans to use reason. To not act on a categorical imperative is to act immorally. Autonomy is the highest principle to deontological ethics and with that comes obligation before rights (O’Neill, 147). Kant’s argument, in relation to human obligation, builds on the basis that human rights divide human liberty (O’Neill, 150). Abstract from any specific universal moral or law, deontology requires a categorical imperative for each situation. In the case of humanitarian aid Kant would ask if we should act on a maxim of the perspective principle, in this case “should we always send aid to human beings in need” and specifying in relation to need how much aid must be given. To determine how much aid, singers marginal utility perspective as a means for when to stop giving aid is useful. To determine if this maxim should be used, non-biased reason must be applied. Seeing all people as an end-in-him or herself and putting value on all human life and the continuation of humanity. As O’Neill sees it, famine is a natural disasters but creates problems only when social structures are inadequate (O’Neill, 143). This may lead a deontologist to solve the famine using social structures as a starting point. In comparison, Discourse Ethics, as defined by Jurgan Habermas, attempts to define universal principles in order to create this ethical framework. Habermas uses Kant as a starting point when he states that moral claims should be universal in order to grant a critical standard of judge-able criteria. He believes that “ethical theories that embed ethics in social and cultural contexts as inherently conservative and incapable accounting for moral progress” (Hutchings, 43). This is a conflict as is becomes very difficult to detach morals form the culture in which they were created. But even so, Habermas goes on to say that Discourse Ethics depends on ‘communicative action and reason’ which is is only possible in the absence of manipulation and coercion, and therefore is based on the free agency of the people. While this should be easy enough to obtain, unfortunately there is scarcely a state that allows for such open dialogue, as there is some sort of coercion within every society. But he goes on in his attempt to separate “between evaluative claims about the good life and normative claims about the universally right” (Hutchings, 46), because through this it would be possible to create absolute truths. Through these fundamental challenges in Discourse Ethics, it becomes difficult to visualizes it’s actual application. If one was respond to the famine in Somalia through the lens of Discourse Ethics, because it is so disconnected from personal responsibility and detached form contextual ideals, it may create a lack of compulsion to grant aid. But in the same vein, there may be a sort of obligation to help those who are under coercive powers in so that they may obtain a state of discourse. There is also and intense feeling of compliance under universal principles, because if one was to defy these fundamental truths, they become personally responsible for any suffering they do not aid, and in this Discourse itself becomes a sort of manipulative force, similar to the very powers it tries to eliminate. Despite all of these conflicts, is it impossible to have an entire globe to agree on these universal principles because it is impossible to eliminate cultural context. As is evident through these descriptions and examples, each of these theories has its own strengths and weakness, and none of them seem to be a perfect fit. It is difficult for a singular theory to encompass and account for all the complexities that surround and ethically confused situation. Because of this, the best way might not be to align oneself with one singular theory, but to pull from aspects of all of them in order to create the ideal framework. Two things to consider and define are the consequences and the goals specific to each theory. Through understanding it will be possible to grant aid to those in need, and end the suffering that can be alleviated through humanitarian aid.