the story of starbucks - StudentTheses@CBS

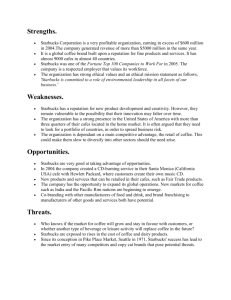

advertisement