cavendish 18607

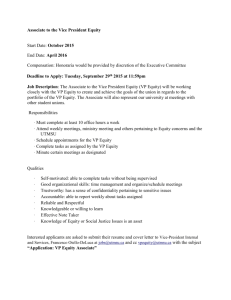

advertisement