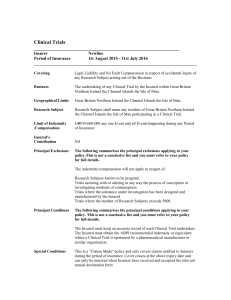

Insurance - Fenwick Elliott

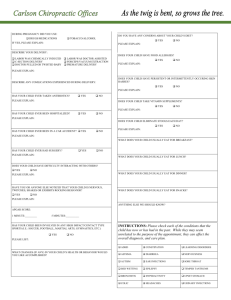

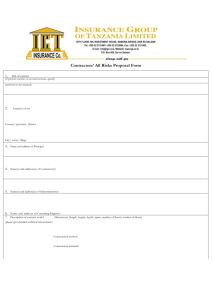

advertisement