philippine regional and provincial differentials in marriage and

advertisement

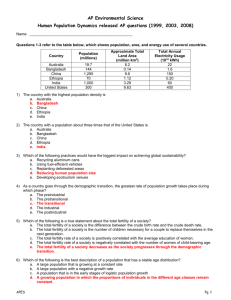

• PHILIPPINE REGIONAL AND PROVINCIAL DIFFERENTIALS IN MARRIAGE AND FAMILY BUILDING: 1960 PETER C. SMITH ABSTRACT. This paper examines geographical differentials in the timing and extent of marriage and childbearing in the Philippines. Province-levelcensus data for 1960 are utilized to estimate fertility levels and to describe marriage patterns for Philippine provinces. A typology of regional divisions respecting timing of marriage, level of fertility, and universality of marriage is also presented. Differentials on the province level are presented by means of a series of maps. The impact of selected independent variables upon these differentials is assessed using correlation and multiple regression. A concluding section discusses the implications of the present findings for subsequent investigations into areal variations in Philippine marriage and family-building patterns. • Geographical differentials in marriage and childbearing in the Philippines have rarely been examined systematically, largely because provincial and municipal-level fertility estimates have not been readily available. The 1939 province-level parity data - the first data of this kind to become available for the Philippines - were examined by Taeuber (1960), but no thorough province-level analysis has been conducted since. In particular, the 1960 Census parity data for provinces have never been exploited fully, although Regudo (1965a) inspected these data for three census regions and Pascual (l971) made some use of 1960 parity information. National demographic parameters, on the other hand, have received more attention, for two reasons. First, most data since 1939 have been adequate only for national- level analysis, either because of small sample sizes or the failure to tabulate for sub-national units. I Second, recent national-level analyses have been motivated by the need for a baseline with which to evaluate the family-planning program now underway. However, while the primary stress of most 159 • demographic analysis in the Philippines has been upon national estimates and projections, there is no reason to expect areal uniformity with respect to human behavior - certainly not in the Philippines. The nation is a melange of races and ethnicities, and amalgamation has only just begun. The discontinuous island environment is a fundamental source of areal variation - in both the quantity and nature of exploitable resources. Arrangements for the getting of livelihood, therefore, as well as cultural systems, vary widely over the landscape. The result is considerable areal variation respecting social institutions, normative understandings and, ultimately, patterns of individual behavior. The dynamic process of family building and reproduction is one realm in which these variations are clearly manifest. Geographical differences in family structure and in the timing of family building are easily documented with simple indexes, as this paper demonstrates. Marital patterns vary considerably across regions and provinces with respect to both timing and universality, and marital fertility displays an equally important (though smaller) degree of variation. In this paper we 160 utilize the 1960 Census parity data to describe these differentials for 1960, primarily by means of a series of maps. Employing correlation and regression procedures, we go on to isolate some of the determinants of interprovincial levels of marital fertility and the timing of marital union. In a concluding section we indicate some areas in which additional research seems warranted. The 1960 data utilized here are essentially similar to those for 1939 examined by Taeuber, but out effort differs from hers in several ways.! We utilize, in addition to the usual measures, a new index of fertility first presented by Coale (1965, 1969). The index is suited to aggregate areal data and is efficient at sorting out marriage and marital fertility components of overall fertility. In addition, we provide some measure of cross-verification of results, since we examine divergent types of data and not only those on average parity. The present report updates Taeuber's findings from the 1939 Census, performing the analysis of 1960 Census data called for in her paper of that year. As Taeuber noted then, women of completed fertility at the time of the 1939 Census (i.e., aged 45-54) were born at the end of the 19th century. Most of them were married before the First World War. In most provinces, 85 to 90 per cent had never attended school. The women and their husbands had secured their livinglargely by agricultural or other local subsistence activities or with handicraft production. Social and economic differentiations were not absent, but they were limited (Taeuber 1960: 110). For women of completed fertility in 1939, the relationship of marriage and fertility patterns to social and economic variations was surprisingly weak. Women aged 45 to 54 in 1960, on the other hand, were progeny of the 20th century, born shortly before World War I but after the revolutionary upheavals. By that juncture a new colonial power and yet another social and cultural overlay had been imposed. These 20th century cohorts, the present analysis suggests, have been responding somewhat more to new social and economic pressures and opportuni- PHILIPPINE SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW • ties, and somewhat less to older ethnic and religious forces. A brief comment on levels of analysis is in order. The ecological perspective taken here is meant to supplement differential fertility studies on the individual level. While individuallevel studies are essential to understanding childbearing phenomena, some of the determinants of individual-level fertility behavior are essentially societal or structural (vis-a-vis the household) in nature. Thus, for example, the sex ratio, an aggregate concept, affects age at marriage for females, which in tum bears upon overall fertility levels. This is a relationship which can be highlighted only by ecological data for local areas. In addition, determinants of childbearing which are individual level in nature often have characteristic spatial distributions; independent variables reflecting ethnic status and province socioeconomic status (SES) ,__ levels are cases in point. It is ultimately intended to carry the present effort to the municipal level, where marriage and fertility differentials have never been assessed quantitatively. Our experimentation here with age-structure estimates of fertility was conducted with this intention in mind. Extensions will be made across time as well, using 1939 and earlier census information for provinces and municipalities as well as data forthcoming from the 1970 Census. The methods and computer programs developed here can be applied directly to the new data as they become available. In the following section we summarize the available census data on marriage and fertility and describe the indexes that are utilized in this analysis. The Appendix presents a comparison of some of the indexes, and provides some notion of their consistency and accuracy. • Province-Level Indicators ofMarriage and Fertility The Data. Reliable demographic data for sub-national areal units are only available from the census rounds. The 1903 and 1918 censuses contain information on sex and civil status by • • • • REGIONAL ANDPROVINCIAL DIFFERENTIALS IN MARRIAGE AND FAMILY BUILDING province (age breakdowns are provided only in 1903), while the 1939 Census shows civil status by age and sex, and gives this information for municipalities as well as provinces. As we noted above, this is the earliest source of retrospective data on children ever bom (CEB) to ever-married women. Similar marital-status information is available for 1948, but only national-level parity data were tabulated. In 1960 marital status by age and sex is available for provinces though not for municipalities, while province-level data on children ever bom are available for ever-married women in a 10-per-cent sample of enumerated households? The 1960 Census suffers from the usual problems of census administration in an underdeveloped country. Age inaccuracies are of course present, including some underenumeration of children (Lorimer 1966:281ff.), adjustments for which are considered briefly below. The sequence of questions asked of ever-married women in 1960 seems superior to that in 1939 but not as elaborate as in the bi-annual surveys of 1956 and 1958 (Regudo, 1965a:8). In 1939 enumerators simply recorded the "number of children ever bom to this woman." In 1960 women were asked how many children they had borne by that time, and in addition, the number of these currently alive. In contrast to the 1956 and 1958 Philippine Statistical Survey of Households (PSSH) surveys, however, they were not asked how many children they had borne alive who had died subsequently. Despite the sequence of questions employed, however, the parity data for 1960 seem slightly inferior to those for 1939. This is indicated by a comparison of 1939 and 1960 completed children ever born. Where national completed fertility in 1939 was 6.36 CEB per woman (aged 45-54), it was 6.02 CEB in 1960 (aged 45-49). Since current consensus places actual completed CEB in 1960 at about 6.8 (Lorimer 1966) or perhaps somewhat less, both census estimates of completed fertility apparently understate true levels, slightly less so in 1939 than in 1960. Nevertheless, there is no reason to suspect that errors of this kind distort fertility 161 differentials in 1939 or in 1960. The present analysis stresses areal variations in fertility and only secondarily does it examine actual fertility levels. Computation of indexes. In the absence of a viable system of vital registration, the available indexes of fertility in 1960 are of two types: (A) measures derived from age-sex information, and (B) measures based on responses with respect to past childbearing. Specifically, the following fertility indexes have been examined: A. Based on age-sex structure AI. child-woman ratio (0-4/15-44); A2. child-woman ratio (5-9/20-49); A3. birth rate from census pop. 0-4 and reverse survival; A4. birth rate from census pop. 5-9 and reverse survival. B. Based on retrospective responses with respect to fertility B1. cumulative CEB by age 45-49; B2. birth rate based on age-specific fertility rates derived from the 'Brass' technique applied to cumulative CEB; B3. total fertility rate based on age-specific fertility rates. Marriage patterns are readily indexed by proportions single in five-year age groups. In particular, the per cent single at age 20-24 is a sensitive index of the timing of movement from the single to the married state, while the per cent ever married by age 45-54 is a useful indicator of the universality of marriage in the populations in question. Finally, singulate mean ages at marriage (SMAM) are easily calculated from these data (Hajnal 1953) and afford summary measures of the timing of marriage within the areal units under study. Our child-woman ratios (AI and A2) were computed directly from census figures, without 162 adjustment. In the absence of enumeration error, Al and A2 are' indexes of fertility centering 2.5 and 7.5 years prior to the census; in this ideal circumstance, differences between them reflect changing fertility in the pre-census decade. In the present"case, however,' as the Appendix indicates, the 1960 Census is n<;>t error-free, and differences between Al and A2 . in fact reflect the greater under-enumeration of the youngest age group. Birth rates by reverse survival (A3 and A4) were also based upon census age-sex information. Enumerated.. populations aged 0-4 and 5-9 in 1960 are the survivors of birth cohorts of the periods 1955-1959 and 1950-1954, respectively. The reverse survival of these populations, therefore, yielded estimates of the original sizes of these cohorts," Respective. . mid-period populations, estimated by assuming a constant rate of growth over .1939-1960, formed the denominators with which birth rates were calculated.! . The 1960 census' retrospective information: was available, although unpublished, in the' form of cumulative children ever bomto ever-married women' in five-year age groups (Bt). Application of the Brass graduation procedure (Brass 1960)6 produced for each province an age-specific fertility schedule correspondingto the observed schedule of cumulative children ever born. The sum of these age-speci'fie fertility rates is of course the total fertility rate (B3). When the rates are applied to enumerated females by age in 1960 they also yield an estimate of the provincial birth rate (B2). The Appendix provides a brief evaluationof the usefulness of these various indexes, by comparisons between them across regional and provincial areal units. As a consequence of this evaluation we elected to work with the paritybased indexes rather than those based on age structure. In particular, we have relied heavily upon a set of analytic indexes based on the parity information. These indexes are described in the section following. Additional indexes. The' overall level of fertility of a province reflects two underlying . PHILIPPINE SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW components: (a) the prevailing pattern and level of m~rital. fertility, and (b) predominant custom respecting the timing of marriage. It is very helpful to separate these components in attempting to discuss fertility differentials, especially if one is searching for causal patterns. Factors bearing upon one component may be 'largely unimportant with respect to the other, . as w~ see below. Simple indexes conveniently sorting out these two components of overall fertility level havebeen'developed by Coale for application in a study of the fertility transition in European provinces (Coale 1969). Coale's indexes require age-specific fertility rates and numbers of women by age and whether ever-married. This .information is combined with an hypothetical maximum fertility schedule - the age-specific fertility schedule of married Hutterite women - and three' indexes are generated, If (an overall inde~ of fertilityj, 'Iin.. ...<an index of female proportions married), and" Ig (an index of marital fertility). 7 . . • The computational formulas are: . If = 1m. = Ig - '. ~ Wi fi ~ Wi Fi ~ m'1 Fi w·1 F·1 and Wi f-1 mi Fi , where ~ . ~ ~ The fi are observed age-specific fertility rates, Wi and m] are numbers of women and married women, respectively, and F] is the fertility schedule of married Hutterite women." The index i ranges in five-year intervals from 15 to 50. The Hutterite schedule of marital fertility serves as a hypothetical maximum level, and the indexes express fertility relative to this standard.? Thus, If indexes overall, actual fertility relative to that had' the Hutterite schedule . prevailed among all women, including the unmarried, in.'·the population in question. Ig • • REGIONAL AND PROVINCIAL DIFFERENTIALS IN MARRIAGE AND FAMILY BUILDING indexes actual fertility relative to an hypothetical maximum within marriage. 1m indexes the effect on fertility of proportions married. 1m can be re-stated as a weighted average of proportions married, wherein the weights are the Hutterite marital fertility rates. Thus, highfertility ages are weighted most heavily. The indexes are really relative measures of fertility performance, indirectly standardized for age within the childbearing period with the Hutterite marital fertility schedule as the standard. RegionalDifferentials in Marriage and Fertility In this section some observations are made with respect to regional differentials in marriage and childbearing. The key data for this discussion are given in Tables 1 and 2. • . • Marriage. Marriage in the Philippines is not particularly early for a traditional society, nor is it anything like universal for females. More than 40 per cent of Filipino females aged 20-24 in 1960 were still single, and 7.3 per cent of those 45-54 had never married at all. Hajnal's SMAM for the Philippines in 1960 is a moderately high 22.3. 1 0 The ten census regions exhibit some interesting differentials. There is little variation in mean age at marriage, except that Manila exhibits a somewhat older average age while marriage occurs early in the frontier-like Cagayan Valley area and in Mindanao. Per cents single are much more sensitive indexes of the timing of marriage, however. Thus the per cent single at age 20-24 is quite high (70 per cent) for Manila, but is low for the Bicol area (Region VI) and Mindanao (Regions IX and X), in addition to Cagayan. Delayed marriage in the metropolitan center is of course expected, while the areas of early marriage are all rapidly expanding agricultural areas with relatively high sex ratios. I I The birth rate. The three independent birthrate estimates shown in Table I are mutually consistent for the total Philippines, but are much less so for many of the regions. With the exception of Region VI, estimates based on the 163 enumerated population 5-9 are higher than those based on persons aged 0-4, a finding which reflects the differential underenumeration of the two age groups involved. In only two cases is the Brass estimate higher than the average of A3 and A4. In general, this average seems a plausible choice as a single estimate, since averaging cancels the effect of those age-response errors contributing to a net shift across age five. Only two regions (II and VI) have estimates differing by more than four births per thousand, and the Region-VI estimates are nevertheless broadly consistent, both indexes indicating relatively high fertility levels. Only Region II presents a serious anomaly. The B::ass estimate here is only 34 births per thousand, the lowest of the regional levels, while agestructure information places the birth rate at close to the national average. The estimate from retrospective information seems to us most accurate, especially in the light of likely distortions in age structure due to out-migration."? If. 1m and Ig. Expressed relative to the Hutterite fertility schedule as a hypothetical maximum, Philippine fertility stands at 0.48; marital patterns alone reduce fertility by 35 per cent, while fertility within marriage is at about 75 per cent of that observed for the Hutterites. Of the total "lost" fertility, about two-thirds is due to the timing of marriage while the remaining third reflects less-than-maximum marital fertility. The census regions vary considerably on these indexes (see Table 2). In terms of sources of lost fertility, however, the marriage pattern is consistently most important, accounting for three to four-fifths of the total lost in each case. Figure I arrays the ten census regions with respect to their scores on 1m and Ig, establishing graphically a typology of regional units respecting "early-late marriage" and "high-low marital fertility" dimensions. (The horizontal and vertical lines indicate respective national levels on Ig and ImJ Six of the 10 regions show significant deviations from the national level on - a.. ~ • • • I • ::00 !j sz > r- ~ o -e ::00 o < Table 2 ~ Indexes ofoverall fertility, marriage pattern and marital fertility, and decompositions ofhypothetical maximum fertility: total Philippines and ten census regions, 1960 Census Indexes Philippines Manila Ilocos Mt. Prov. II Cagayan Central Southern Valley Luzon Luzon III IV V ;; t"" o =r; region Bicol VI "r1 trl Western Visayas Eastern Visayas North Eastern Mindanao South Western Mindanao VII VIII IX X ~ ;; etI:l Z Coalefertility indexes 1) If 2) 1m 3) Ig ::00 3: .48 .65 .75 .37 .49 .76 .41 .69 .60 .56 .78 .72 .52 .67 .78 .50 .66 .76 .59 .72 .82 .53 .66 .80 .51 .69 .73 .55 .75 .72 .55 .75 .74 > ::00 ::00 ;; C) trl Decomposition of maximum fertility 4) 5) 6) 7) 8) Actual/maximum (%) Lost within marriage/maximum (%) Lost outside marriage/maximum (%) Lost within marriage/total lost (%) Lost outside marriage/total lost (%) 48.36 16.34 35.30 31.65 68.35 37.42 11.78 50.80 16.80 83.20 40.98 27.70 31.32 42.98 57.02 56.03 21.58 22.40 43.55 56.45 52.49 14.83 32.68 27.60 72.40 50.19 16.21 33.61 28.98 71.02 59.31 12.70 27.99 26.57 73.43 52.87 13.12 34.01 24.47 75.53 51.01 18.45 30.54 33.37 66.63 54.65 20.82 24.52 40.40 59.60 55.32 19.20 25.48 37.98 62.02 ~ o "r1 > 3: i= 0< t:I:l c:: i= o ~ - a-. V> 166 PHILIPPINE SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW at least one of the dimensions. Bicolanos both marry early and exhibit uniquely high levels of marital fertility, and actual fertility (If) for Region VI (.59) reflects this pronatalist cultural configuration. Three regions (III, IX, and X) show relatively high values for 1m. Overall fertility in these areas is near the national average, but only because marital fertility is moderate. Each of these three regions is a "frontier" area characterized by heavy in-movement and the rapid extension of agriculture to newly developed territories. Cagayan and northeastern Mindanao, particularly, have been populated by Bocanos and Visayans, respectively, escaping rural saturation in their native regions. Early marriage for females in these areas is probably a direct function of the high frontier sex ratios which prevail there (see the correlation and regression analysis below). Southwestern Mindanao, in addition, has a large Muslim population with a traditional pattern of early marriage for females. Manila, with a relatively low If, exhibits a very late age at marriage but moderate to high fertility within marriage. Lastly, the Ilocos area is unique in that it maintains a relatively low level on Ig - fertility within marriage. While it commonly has been felt that the low overall fertility of Ilocanos is to a considerable degree the result of delayed marriage, the" present fmdings indicate that the relatively low fertility of this region is largely due to a unique "semi-modern" level of childbearing within marriage.l ' Figure 1 incorporates a third typological dimension - "universality-non-universality of marriage" for females. Interestingly, the four non-unique provinceson 1m and Ig are also very near 'the national level (about 7 per cent never marrying by age 50) on this component of family building. All the regions with early marriage (III, VI, IX, X) also exhibit a pattern of nearly universal female marriage(about 3 per cent never marrying). Ilocos ana Manila are, again, unique; they show relatively large pro- .80 o Manila .70 Per cent Never Marrying o High (8,1 +) • Average (6,0-8,0) .60 x Low (-6,0) .50 .60 • o Ilocos .70 .80 Fig. 1 - Regional Valueson 1m, Ig and Per Cent Never Marrying . r I I ~. REGIONAL AND PROVINCIAL DIFFERENTIALS IN MARRIAGE AND FAMILYBUILDING portions of females never marrying - around 12 and 10 per cent, respectively. Thus in the two regions with uniquely low overall fertility, delayed marriage (Manila) or low marital fertility (Ilocos) combine with high levels of nonmarriage to dampen fertility. The Bicol area - the region where fertility is highest - apparently possesses a social system and attendant cultural values favoring early marriage, high marital fertility, and the eventual marriage of nearly all females. Province-Level Differentials • Figures 2 through 5 portray the distributions . 14 . dexes across provinces, o f the summary ill Respecting If, overall fertility, only one in five provinces is at or below the national level of 0.48. Of these 10, three are in the Ilocos area. Manila and two adjoining provinces are below average, perhaps reflecting the modernizing impact of proximity to the metropolitan area. Iloilo in the Western Visayas is below average, as is Cebu in the Eastern Visayas. Both these provinces contain regional metropolitan centers (Iloilo and Cebu). The below-average score for Sulu is probably the result of faulty data and should be ignored. IS In overview, excepting two subcultural areas for which low levels may be statistical artifacts, relatively low fertility is found in three geographic areas, including provinces of two types. Manila, Bulacan and Rizal, and Iloilo and Cebu, either are, or are dominated by, urban centers. A causal relation is clearly suggested, though by no means demonstrated. The three Ilocos provinces, on the other hand, are relatively backward; their low fertility levels would seem to derive from cultural milieu rather than level of modernization. Figures 3 and 4 serve to decompose the overall patterns just examined. 1m, for example, exhibits a quite dissimilar arrangement of relatively high and low values. The provinces of early marriage (1m;;;:: .75) are almost uniformly located in frontier and relatively undeveloped areas, and of course in Mindanao - both a frontier and the home of an early-marrying 167 cultural minority. Few provinces show a distinctly late age at marriage, and only two (Manila and Rizal) are below an 1m of .61. Iloilo and Cebu have relatively late marriage ages, as do Ilocos Norte and Ilocos Sur. Marital fertility does not exhibit a great deal of variation. It is relatively high ~ .80) for three Tagalog provinces (including one adjacent to Manila), a good part of Bicolandia, Masbate and Samar in the Eastern Visayas, Antique and Negros Occidental in the Western Visayas, and for Misamis Occidental on Mindanao. Relatively low marital fertility is seen only in the Ilocos provinces, excluding Abra. Marital fertility is uniformly near, at, or above the national average in all provinces South of the Tagalog area (again, Sulu's low Ig is not taken as an accurate indication of Sulu marital fertility). Examining Figure 2, we noted that outside the Ilocos area below-average fertility is found only in the vicinities of Manila, Iloilo, and Cebu. Figures 3 and 4 indicate that these levels on If derive from different sources. In economically backward Ilocos, marital fertility is somewhat low. In the "urban" provinces marriage is delayed while marital fertility is undiminished. Philippine provinces show considerable variation with respect to the universality of marriage (figure 5). The per cent of females married by age 50 ranges from 98.6 in Lanao (del Norte and del Sur) to a very low 81.2 for Ilocos Sur. Overall, 93.7 per cent of Filipino women eventually marry. One in five provinces shows one-tenth or more of all females never marrying. The geographical distribution of this index is enlightening. Relatively high proportions never marrying are seen in the provinces forming the heartland of each of three major cultural groups - Ilocano, Tagalog, and Visayan. Each of these areas is characterized by a degree of out-movement to neighboring frontiers, suggesting that the per cent still single at age 50, as well as per cents single at younger ages, may be the product of imbalanced sex ratios, rather than underlying cultural prescriptions. 168 PHILIPPINE SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW p , , I • low <'48 and below) ~ medium (.49 - 59) LUZON ~ high (.60 and over) c=J inadequate data .• ~ o flO • ~. • Fig. 2 - Index of Overall Fertility (If) REGIONAL AND PROVINCIAL DIFFERENTIALS IN MARRIAGE AND FAMILY BUILDING 169 J I •m J LUZON I late ( .60 and below) average (. 61 II early (.70 - .74) ~ very ear l y (,75 and over o co •o ~..:.. • N ~ SlIlu ., .; o MINDANAO Fig. 3 - Index of Marriage Pattern (1m) .69) 170 PHILIPPINE SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW •m LUZON low c. 69 medium (.70 - .79) ~ high (.80 and over) D inadequate data •• . ~ and below) I 1 I i Ii ! 1 I i .~ • ... .>'" MINDANAO • Fig. 4 - Index of Marital Fertility (I g) • REGIONAL AND PROVINCIAL DIFFERENTIALS IN MARRIAGE AND FAMILY BUILDING LUZON III very low (89% or below) ~ moderately low (90%-93%) III moderately high(94%-g6%) ~ very high (97% and over) ,. o e,• , ~ • o e, • ~ . Sulu ~ MINDANAO .~ • 171 Fig. 5 - Per Cent of Females Ever Marrying 172 PHILIPPINE SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW Determinants ofMarriage Pattern and Marital Fertility In this section we employ correlation and multiple regression analysis to explore some of the apparent causal connections between marital fertility, the prevailing marriage pattern, and selected explanatory variables.l" In order to be as brief as possible, the analysis stops short of a full elaboration upon the directions and magnitudes of the regression coefficients estimated by each predictive equation. Most of the major points we wish to make can be shown by means of zero-order correlation coefficients. These are supplemented by coefficients of multiple determination (R 2 ) for specific equations. Though a number of alternate dependent variables might well have been utilized, we have limited the present analysis to If, 1m, and Ig. The reader is by now familiar with the behavior of these indexes. In particular, a simple relation among them may have become apparent: If = 1m' Ig. This is an extremely useful characteristic of these measures since as a consequence their logs combine additively: In (Ie) =In (1m) + In (lg). Utilizing (natural) logs we can therefore decompose If in a regression framework, simply by regressing If on 1m and Ig.1 7 The R 2 for this equation is unity, since the relation is fully determined by an arithmetical rule. The beta weights (standardized partial regression coefficients) are 0.81 and 0.80 for 1m and Ig, respectively. That is, interprovincial variation in the overall level of fertility is accounted for in equal proportions by differences in marital patterns and varying levels of fertility within marriage. 1 8 The correlation between 1m and Ig across province units is -0.24, prompting a causal interpretation similar to that for European nations suggested by Coale (I 965). In Europe the negative association apparently occurs because increased control of marital fertility (lg) over time, brought about by economic change, has allowed a rise in 1m (earlier marriage) while overall fertility has undergone a substantial decline nevertheless. 1 9 As we now see, how- ever, the causal pattern in the Philippines appears to be quite different. The independentvariables. Let us distinguish several types of potential influences on 1m and Ig. A wide range of cultural, attitudinal, and behavioral differences across areas are simply indexed by classifying provinces as to dominant ethnic group in 1939 (see footnote 5, Table 4). Economic level can be measured by a myriad of provincial characteristics. We have elected to utilize several characteristics of families, to wit: per cents with electric lighting, piped water supply, modern toilet facilities, and strong house construction. These and other household SES measures are highly intercorrelated, so that the choice of specific measures is not of critical importance. Crude density is used here as a rough measure of agricultural economic opportunity, in part to maintain comparability with other studies which have used this index. Indexes of literacy include educational attainments and rates of school attendance for selected age groups as well as per cents actually reading magazines etc., among those who were literate in 1939. Religion is indexed by per cents Muslim and Roman Catholic. The availability of single males of marriageable age and their propensity to marry are indexed by the sex ratio at the marriageable ages, and by male SMAMs and per cents ever marrying. Some additional details on the independent variables are given in the footnotes to Table 4. The findings. The utility of separating marriage pattern from marital fertility when seeking to explain overall fertility levels is apparent from the zero-order correlations shown in Table 3. The stub lists a series of measures indexing a variety of forces presumed to be acting upon overall fertility and its components. In a number of cases, associations with If, 1m, and Ig are quite dissimilar. Often, in fact, signs differ. Socioeconomic level (indexed by physical characteristics of dwellings) is negatively associated with overall level of fertility, but this effect is felt exclusively via the association between socioeconomic level and the marriage pattern. The association with level of marital fertility is negligible and, if anything, positive. Ii • • 173 REGIONAL AND PROVINCIAL DIFFERENTIALS IN MARRIAGE AND FAMILY BUILDING Table 3 Zero-order correlations between selected variables (1939) and Ir, 1m, and Ig in 1960: 50 province units , ,.. r t I I Variable 1m Ig If -.56 -.58 -.56 -.60 -.52 .02 .09 .00 .16 .16 -.44 -.40 -045 .02 -.4() -.15 -.07 -.44 .26 .24 .19 .26 .00 12) Per cent Roman Catholic 13) Per cent Muslim -.24 .20 -.27 14) 15) 16) 17) .11 -.78 -.80 .70 .19 .10 .20 -.19 1) Per cent strong construction 2) Per cent electric lighting 3) Per cent modern toilet facilities 4) Per cent running water 5) Per cent of labor force professional 6) Density 7) 8) 9) 10) 11) Per cent females 20-24 with grade IV ed. Per cent females 14 + with grade IV ed. Per cent population 15-17 attending school Per cent female literacy 20-24 Per cent readership of those literate -043 -045 Sex ratio (marriage age) Male per cent single 20-24 Male SMAM Male per cent ever married -046 -.36 -.30 .O~ .12 -.19 -.16 -.35 047 .16 -.05 -.30 -.54 -048 040 Table 4 Coefficients of multipledetermination (l?2) and F-Ratios, regressions of1m and Ig on selected setsof independentvariables • Independent Dependent variable , Male information- Economic informations Religion3 variables Regions Ethnic groupO Combined influencesf 1m I • iP F ratio .62 21.41** .35 7.53** .02 .23 .01 .83 1.56 2.64* 0.94 40.00** Ig R: 2 F ratio .17 .15 .19 3.53* 3.20* 6.86** .28 3.11 ** .13 .18 2.36* 2.78* lSex ratio (marriageable ages); percentage single (males 20-24); males SMAM; male percentage ever marrying 2Percentages of families having modern toilet facilities, electric lighting, piped water, homes of strong construction 3Percentages Roman Catholic and Muslim 4Nine dummy variables distinguishing ten census regions 0Five dummy variables reflecting six ethnic groups: Tagalog, Cebuano, 1I0ko, Ilonggo, Bikol, other 6Percentage of labor force professional, percentage of families with houses of strong construction, percentage of aged 15-17 attending school, percentage Roman Catholic, sex ratio (marriageable ages), SMAM (male). *Significant at the .05 level **Significant at the .01 level 174 The per cent of the labor force in professional occupations, another indicator of provincial economic level, is associated with the three dependent variables in a similar manner. Density is clearly related to diminished fertility, or perhaps more accurately, the availability of land (i.e., frontier status) is associated with high levels of childbearing. The relationship is exclusively via the timing of marital union, however. Marriage comes later in the provinces which are most heavily settled. The several education-literacy variables relate in varied ways to the fertility measures. Educational attainment of both sexes combined has a slight positive association with overall fertility, while the correlations between school attendance (both sexes) and female literacy and overall fertility are negative. The level of media readership of those who are literate is also associated negatively with overall fertility. All these measures except the last show small positive associations with marital fertility. Literacy and educational attainment uniformly show negative associations with 1m. As expected, 1939 school attendance and female literacy at the peak period of fertility show the strongest negative relationships with 1m. In causal terms, female entrance to marital union seems to be delayed by continued school attendance beyond age 15, and by heightened literacy. Differences in religious composition are associated with fertility level. Heavily Roman Catholic provinces tend to have the highest fertility, while the prevalence of Islam reduces fertility. The relationships of these indexes with 1m and Ig further clarify this pattern. Roman Catholicism is associated with high marital fertility and somewhat delayed marriage, while the prevalence of Islam displays the opposite associations - i.e., with early marriage and relatively low marital fertility. The variables reflecting male marriage patterns naturally can be expected to relate to 1m rather than Ig. Briefly, and not suprisingly, early marriage (a high 1m ) is strongly associated with the availability of males no matter how indexed. To summarize, associations with If often PHILiPPINE SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW • conceal quite different relationships with 1m and/or Ig. Opposite associations with 1m and I g in some cases lead to diminished relationships with overall fertility (note the SES measures). On the whole, associations are closer between independent variables and 1m than between these measures and Ig. ~ Multiple associations between groups of explanatory variables and the component fertility measures are given in Table 4. 20 The variables just examined are grouped into three types of influences- demographic (availability of males), economic (household characteristics), and religious. In addition, a dummy variable procedure (Suits 1957) allows us to examine the explanatory power of regional membership and dominant ethnic group with respect to the dependent variables. Both multiple regression and analysis of variance are founded upon the general linear model (Fennessey 1969), and dummy variable regression is in fact analysis of variance in another guise. Table 4 therefore shows, for each regression equation, the F ratio and corresponding coefficient of multiple determination (If). Equations can be assessed by examining either -2 F ratios or R s. Several tentative generalizations seem warranted. First, cultural milieu, indexed by religious and ethnic compositions, accounts for marital fertility more effectively than for the pattem of entry into marital union. Second, economic level explains one-third the variation in 1m but much less of the variation in Ig (male information is naturally the best single predictor of 1m ) . Third, in general, 1m is better predicted with these variables than is Ig. Such were the major patterns of influence in the post-war years before 1960. Are these apparent flows of influence different in any way from those prevailing during the interwar period and before? We noted at the outset Taeuber's general findings from the 1939 parity information. Direct comparisons between her results and the present results are not possible, since our marriage and fertility measures are not com- l 1 1 • I • I REGIONAL AND PROVINCIAL DIFFERENTIALS IN MARRIAGE AND FAMILY BUILDING parable, and in any case, Taeuber stopped with a discussion of selected zero-order correlations. We can make some general observations, however, by shifting our discussion to two dependent measures available from both the 1939 and 1960 censuses: the per cent of females single at age 20-24, and the number of CEB per ever-married woman aged 45-49. These are rough measures of marriage pattern and marital fertility, respectively. These dependent measures were regressed upon selected sets of (1939) independent variables. The resulting coefficients of multiple determination are shown in Table 5. For the present purpose the relevant comparison is between years for either of the dependent variables. In the earlier period, just as in 1960, ethnic status (cultural milieu) had a greater influence on marital fertility than on the marriage pattern. But the influence of this variable, particularly upon marital fertility, has diminished over 175 time. The impact of availability of males on age at marriage has likewise diminished, though it wasnot great at either date. The economic measures (house construction and electric lighting) have their greatest effect upon marriage age, but have significantly increased in importance over the period vis-a-vis both dependent measures. The central assertion put forth in the introduction to this paper is clearly supported by these regressions: economic differentials are becoming more important as older ethnic divisions (cultural milieu) become less important as causal determinants of marriage and family building. Summary and Implications Inferring individual-level patterns of causation from aggregate information is hazardous, and the results of such an effort must always be Table 5 • Coefficients of multiple determination (R 2;1 for selected predictive equations: 1939 and 1960 Dependent Independent variable • Ethnic status 2 [A] Sex rati0 3 [B) Per cent households of strong construction [Cl] Per cent households with electric lighting [C2] Sex ratio and ethnic status [A + B) Strong construction and ethnic status [A +Cl] Sex ratio and strong construction [B +C l] Sex ratio, strong construction, and ethnic status [A+B+C l] Sex ratio, electricity, and ethnic status [A + B + C2 ] Per cent single 20- 24 Variable CEB per ever-married woman 45-49 1939 1960 1939 1960 .05 .04 .03 .01 .09 .01 .03 .05 .04 .24 .07 .10 .08 .10 .25 .01 .01 .08 .09 .09 .06 .21 .19 .12 .12 .32 .05 .22 .15 .29 .1.7 .24 .18 .33 .09 .25 lCorrected for loss of degrees of freedom. 2Entered as five dummy variables: Cebuano, lloko, llonggo, Bikol, Other. The Tagalog category was omitted. 3Males 21-25/females 18-22 176 provisional. To be sure, marriage and childbearing are experiences lundergone by couples, not provinces. Yet, the' present analysis of interprovincial variations has suggested a number of broad generalizations, and some specific areas for future research seem to be indicated. We have seen evidence of some substantively interesting areal differentials in If, 1m, and Ig. The relatively low marital fertility of the Ilocos, for example, stands out among the regional levels; and, as we have seen, this region is distinct in other respects as well. At the other extreme, the Bicol provinces constitute the only region in which high fertility is uniformly enforced by patterns of behavior within marriage and with respect to its timing and prevalence for successive cohorts of women. Speaking in general terms, our regression results indicate that social-structural, demographic, and socioeconomic influences bear strongly upon the marriage pattern, but that they have much less influence upon patterns of fertility within marriage. This finding contrasts sharply with the historical pattern for European nations, where economic change lowered marital fertility directly, only indirectly influenced age at marriage, and did so by lowering it (Coale 1965; 1969). Yet, variations in marital fertility, as indexed by Ig, do exist. We have seen that they relate more closely to differences in cultural milieu than to mode of economic organization. What cultural factors conspire to create these variations? Potential cultural influences are of several types (Davis and Blake 1956), including amount of abstinence and variations in coital frequency, level of fecundity, and the prevalence of contraception. Broadly, however, these influences are, from the individual's viewpoint, either voluntary or involuntary in nature (hence Henry's distinction between "natural" and purposively influenced fertility). Expressed in terms of the Coale indexes and the assumptions underlying them, we must seek to know whether observed differences in Ig - as for example that between llocos and Bicol - are due to differences in natural fertility" or PHILIPPINE SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW are the result of differing levels of voluntary control. Insufficient information is available concerning the (largely physiological) determinants of natural fertility - typical patterns of sexual behavior, norms respecting nursing, the prevalence of sub-fecundity and sterility, etc. But, the 1968 National Demographic Survey provides extensive information on the prevalence of rational control, or at least the knowledge and attitudes prerequisite thereto. In particular, these and other survey data of the traditional KAP variety can be examined to see whether variables intermediate between background conditions (economic level, literacy, etc.) and fertility and marital behavior can be identified. Thus, for example, although literacy opens new sources of information respecting fertility control, fertility 'cannot be affected unless new knowledge or altered attitudes are forthcoming. The fundamental theoretical and practical distinction between cultural background and economic condition as determinants of marriage and fertility is perhaps portrayed most vividly by contrasting the Ilocos pattern with that of the Cagayan Valley. The former area is the cultural hearth of the Ilocanos, whose unique family patterns we have already described. The frontier-like Cagayan Valley exhibits nearly opposite patterns of marriage and family bulding: marriage occurs relatively early, and marital fertility is relatively high. Yet, its population has for some time been comprised heavily of ethnic Ilocanos,? 2 This seems a clear example of economic condition (in this case, agricultural opportunity) taking causal precedence over cultural milieu, since Ilocanos who have left their dense home provinces and are now living in the wide-open Cagayan area apparently have not maintained the traditional family patterns still exhibited by Ilocanos in llocos. On the other hand, can we easily assume that current patterns of family building among llocanos in llocos are historically rooted; that agricultural density accounts for the current family-building patterns of Ilocanos in their home region? Other regions historically have been as dense for some time (see Vandemeer r', , I •• r , , • [1967] on Cebu), but exhibit different patterns of marriage and procreation. The forces of ethnicity and economic context are perhaps hopelessly intertwined, though research into historical patterns of marriage and fertility within core ethnic areas could no doubt disentangle some of these influences. Much better information is needed on the fertility and marriage patterns of Filipino Muslims. The low Muslim fertility. noted here as well as by Taeuber in the 1939 data may simply reflect poor recall and high infant mortality. On the other hand, detailed data on typical patterns of sexual activity, lactation, etc. may suggest that the observed level is real, at least in part. In this analysis of geographic differentials we have not considered the most common of areal distinctions - that between urban and rural. Urban-rural tabulations are not available for 1960 though they are being included in the 1970 Census tabulations. Our finding concerning the growing importance of economic as distinct from cultural variables suggests that urban-rural differentials will be of increasing importance, as will differentials between rural areas with divergent levels of economic advancement. Appendix: An Evaluation ofFertilityEstimates • 177 REGIONAL AND PROVINCIAL DIFFERENTIALS IN MARRIAGE AND FAMILY BUILDING The fertility measures described in this paper embody a number of choices - some important, most not - respecting procedures utilized and parameters selected. Consistency between independent estimates is our best single criterion of accuracy. Consistency of national-level estimates. Consider the general level of consistency between fertility estimates on the national level when they are based, respectively, upon the retrospective and age structure data. First, the birth rate obtained by the Brass procedure (43.4) compares favorably with the 45.6 births per thousand suggested by Lorimer's (1966:235ff.) age-specific fertility schedule. Both figures are quite plausible. Lorimer's age-specific fertility rates were estimated by assuming what seemed a reasonable level of fertility (TFR = 6.8) together with the age-specific pattern of childbearing indicated by vital statistics information for 1959-1961. The Lorimer and Brass agespecific rates are as follows: Age (years) 15 2025 30 35 40 45 - 19 24 29 34 39 44 49 TFR Lorimer Brass .306 1.565 1.741 1.500 1.083 .545 .006 .437 1.298 1.642 1.402 .869 .354 .055 6.79 6.06 Our Brass estimates are some 12 per cent lower than Lorimer's overall, with higher rates only at the extreme ages. Our estimates are considerably higher for women under 20, but otherwise the two series are quite similar. While the 12-per-cent difference in level may reflect some measure of faulty recall, we do not see adequate grounds for adjusting upwards the Brass estimates for provinces. Region and province-level estimates in this paper are not adjusted, and the reader should bear this in mind. The age-structure estimates of the birth rate are 42.0 and 42.1 per thousand for reverse survival of the O-to-4 and 5·to-9 populations, respectively. These figures are somewhat below the Brass and Lorimer estimates, apparently because of census underenumeration of children; the two age groups seem about equally at fault in this regard. 23 Assuming, for the sake of discussion, that Lorimer's estimated birth rate is precisely correct, we are led to infer that (a) forgetting has had a slight effect on the estimated 1960 birth rate using parity infor.mation, while (b) underenumeration in the 1960 census has had a marginally more serious effect on birth- rate estimates using age structure. There is a gratifying degree of consistency among these estimates of the 1960 birth rate; differences are small and in expected directions. 178 PHILIPPINE SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW A good deal less consistency is evident on the regional and provincial levels, where there is less opportunity for census enumeration problems to be cross-cancelling, where sampling fluctuations begin to obscure the information on children ever born, and where migration differentials influence the results. Consistency across provinces. Consistency across regions is discussed in the body of the paper. Table 6 presents intercorrelations among the several fertility measures across 50 province units. These associations yield another kind of general indication of the comparability and validity of the estimates under review. Correlations are large but not conspicuously so, suggesting that a fair quantity of "noise" is present in the province-level estimates. The average correlations within A (age structure) and B (parity) type estimates are .80 and .89, respectively, while the average A - B correlation is only 0.52. Table 6 Intercorrelations among selected fertility measures: 50 province units, 1960 Fertility indexf A2 Al .85 A2 A3 A4 81 82 A3 A4 81 82 83 .90 .72 .72 .89 .61 .65 .56 .56 .34 .39 .48 .48 .83 .56 .62 .51 .54 .99 .85 .71 ISee text for definitions. One would have hoped for a greater degree of agreement between age structure and retrospective estimates. Restricting consideration to B2, A3, and A4, the three birth-rate estimates, we have, as an experimental exercise, attempted to improve the consistency between these measures in several ways.. B2 is of course influenced by the age structure of the population to which the age-specific fertility rates are applied - other factors constant, high fertility depresses birthrate estimates. As a consequence, standardiza- tion for age (Philippines ~ 960 as standard) raises the initial B2 - A3 and B2 - A4 correlations (both at 0.48) to 0.56 and 0.58, respectively. One of the age-sex enumeration errors at work is an upward shift across age five (Lorimer 1966 :275ff.). This particular source of error can be nullified somewhat by utilizing as the age-structure estimate of the birth rate the average of A3 and A4. The correlation of this averaged measure with the standardized B2 is 0.62. The most important source of error in the reverse-survival estimates is probably the assumption that there is no differential mortality across provinces. In the absence of provincelevel life tables (or any viable mortality estimates for provinces) we have roughly estimated province-specific 5 Lo values on the assumption that mortality differentials are similar, in degree and direction, to differences in province-level indexes of social and economic condition. Even simple indexes of socioeconomic level are not easily available however. Among those readily available for 1960 are Tioleco's (1970) index of "physical development" and Pascual's (1971) simple index of "modernization." The Tioleco index seems most appropriate for the present purpose. This composite index of physical development arrays provinces with respect to a diffuse notion of "level of development," with which level of mortality is no doubt correlated? 4 On the provisional assumption that provinces are Similarly arrayed on level of mortality and level of physical development, and on the further assumption that provincial mortality levels in 1960 ranged between e:'s of 47.5 and 57.5 (the national estimate for 1960 is e~ = 52.5), interpolated values of 10 L, and 5 Lo were obtalned.i " These province level survival values were used to calculate, via reverse survival, the A3 and A4 rate estimates "adjusted" for mortality. These estimates were then averaged (analogous to averaging A3 and A4) and this final estimate was correlated with the standardized version of B2. The resulting correlation is 0.65. •• ( • • r , , , • I REGIONAL AND PROVINCIAL DIFFERENTIALS IN MARRIAGE AND FAMILY BUILDING Taken together, these simple adjustments produce a notable improvement over the original B2-A3 and B2-A4 correlations of 0.48. However, these manipulations - particularly the attempt to account for mortality differentials - are quite arbitrary. They are presented here only in a spirit of experimentation. At most they suggest that the two types of birth-rate estimate under discussion are largely consistent and that further effort would remove much of the remaining "noise." This further experimentation, though well outside the scope of the present research, would payoff richly by generating age-structure estimates of fertility applicable on the municipal level where parity data and other alternate measures are entirely absent. Notes This study was supported by a research grant (92-154) to the University of the Philippines by the U.S. Agency for International Development. The author received a number of helpful comments from his colleagues at the Population Institute, University of the Philippines, where he is currently a visiting lecturer. Concurrently, he is a research associate, Population Research Center. University of Chicago. His manuscript was received November 19, 1971. 1. The Census of 1948 was not fully tabulated (alphabetically) beyond Cavite. The PSSH (now BCSSH) rounds of May 1956, 1958, 1963, and 1968 do not allow province-level tabulation on most characteristics. 2. The reader will wish to compare the present results with her detailed findings, although some comparisons are made explicitly here. 3. This analysis relies upon parity tabulations from a 0.5 per cent sample of households (a five per cent sample of the households sampled in the census enumeration, made available to the Population Institute by the Bureau of the Census and Statistics). 4. For the basic set of estimates (A3 and A4), a single level of mortality was assumed for all provinces. The life table utilized was U.N. Level 65 (e~ 52.5), the 1960 table which Lorimer (1966) selected after careful deliberation. 5LO and lOL5 are .864560 and .823684, respectively. The inverses of these were applied as reverse-survival factors. This level of mortality probably understates slightly the true force of mortality for the Philippines over the period in question (prior to 1960). = 179 5. The Philippine population expanded by 69.29 per cent over the 21.13 years between the censuses of 1939 and 1960. The apparent instantaneous rate of growth for the period is therefore .025. Using Pt/PO = e(.025) (21.13), Pt was calculated for mid 1952 and 1957. 6. The Brass technique involves the use of a polynomial function to translate cumulative CEB into age-specific fertility rates. The procedure was first applied to the 1960 parity data by Regudo (1965a. 1965b). 7. Ig, Coale argues, is an index of "natural fertility." The term, taken from Henry (1961), refers to a level of fertility within marriage which is unaffected by deliberate control behavior, that is. in which the current fertility behavior of couples is unrelated to the numbers of children they have already produced. In his study of European provinces, for example, Coale is interested to see how changes in If over time - from a pre-transition stable level to a post-transition staole level - are accounted for by changes in component 1m and Ig indexes. 8. Note that Ig reflects marital fertility only if all births are legitimate. Four indexes, including a measure of fertility outside marriage, are presented when illegitimacy is not negligible. 9. See Henry (1961). The rates (5x) for five-year age groups from 15 to 50 are 1.500, 2.750, 2.510, 2.235, 2.030, 1.110, 0.305. The youngest age group is shifted downward from the actual married Hutterite level of 3.500 (see Coale 1965:205). 10. Similar information for 57 countries of the Middle East, Asia and Europe are presented in Dixon (1971). The Philippine pattern stands in contrast to most other nations of the Middle East and Asia (25 countries). The SMAM for females, for example, is exceeded only by that of Hong Kong, Japan, and the Ryukyu Islands.The Philippine proportion never marrying (female) is the highest among the 25 non-western countries shown. See Dixon (1971: 217). 11. Sex ratios for Cagayan and Mindanao (Census Regions III, IX, and X) are considerably higher than the national ratios. 12. There has been a heavy outflow of young adults (pascual 1965). The denominator of the rates is thus diminished and fertility is exaggerated. 13. This statement stands even when we attempt a correction for the effect of the out-movement of single females on proportions single. The long-ter:.n out-flow from Ilocos results in an understatement of per cents singlein 1960 and thus in an overstatement of CEB per woman. If therefore is slightly overstated, as is 1m, while the impact upon Ig is indeterminate and probably small, since If = 1m .I g. For example, when nationallevel per cents single are assumed for Ilocos, 1m is .. l.- 180 PHILIPPINE SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW reduced to 0.65 from 0.69, while Ig is increased to 0.63 from 0.60. have claimed Iloko as mother tongue (see Keesing 1962:181). It should be noted that the indexes assume negligible illegitimacy, so that ~ wifi yields the number of legitimate births. Because the census proportions single used here describe de [acto unions, the assumption is not inappropriate. o to 4 and 5 to 9 are available from Lorimer (1966). 14. There were 55 provinces in 1960, five more than in 1939. So that measures could be obtained on both dates, the 50 1939 units were utilized here, with the 1960 provinces regrouped as necessary. 15. Firm data for heavily Muslim areas are sorely needed. Both the 1939 and 1960 censuses show low Muslimfertility. That this reflects faulty responses and not low fertility is a plausible but unverified assumption (see Taeuber 1960:100-04). 16. As symmetric measures, correlations offer us only information on degree of (linear) association between variables. Though inferences respecting causation are always tenuous, the comments offered here seem to this writer justified as provisional statements. Fertility and marriage information is for 1960, while our independent variables are all taken from information in the 1939 Census. Thus the necessary chronological condition for causal analysis is met. 23. Adjusted estimates of the 1960 populations The reversesurvivalof these adjusted populations yields rates which diverge but nicely bracket the 45.6 per thousand figure. Child-woman ratios (AI and A2) 793 and 902 in unadjusted form - are 870 and 841, respectively, when computed from Lorimer's adjusted populations under age 10. 24. Tioleco's composite index of physical development combines 65 pieces of information describing 10 aspects of development - communications, housing, health, etc. The index has a mean of 1.85 and a standard deviation of 2.5 I. Rizal, the highest scoring province, has an index of 22.1, while Batanes has the lowest score, -5.I. 25. Tioleco's index was adjusted only by arbitrarily setting maximum and minimum values at 5.00 and -5.00, respectively. References Agarwala, S. N. 18. The beta weights here are simply ratios of standard deviations (G Im/G If and G Ig/GIf). See Duncan (1966). The logsof 1m and Ig have approximately equal standard deviations. Brass, William 1960 The graduation of fertility distributions by polynomial functions. Population Studies 14(2): 148-62. 19. Norway is an excellent case in point (see Coale 1965: Table 3). Between 1870 and 1960 its If went from 0.33 to 0.22; marital fertility declined from 0.76 to 0.32, while 1m increased from 0.40 to 0.66. Philippine levelsin 1960 are nearly equal to Norway's marital fertility in 1870 and its marriage pattern in 1960. Consequently, Philippine overall fertility in 1960 exceeds that of even pre-transition Norway by 46 per cent (0.48 vs. 0.33). Christ, Carl F. 1966 Econometric models and methods. New York, John Wiley and Sons, Inc. -2 . R • see Christ (1966:509-510). • , .. 17. Substantively, this log transformation has the desirable effect of deemphasizing the role of extreme values in linear measures of association. 20. All R2s shown have been adjusted for number of predictors (loss of degrees of freedom), and consequently are labeled R:2. Since N in this study is only 50, the unadjusted coefficients are generally much greater than the figures given here. For the formula for • 1962 Age at marriage in India. Bombay, Kitab Mahal Private Ltd. Coale, Ansley, J. 1965 Factors associated with the development of low fertility: an historic summary. Paper presented to the World Population Conference. 1965. 1969 The decline of fertility in Europe from the French revolution to world war II. In Fertility and family planning: a world view.S. J. Behrman, LeslieCorsa, Jr., and Ronald Freedman, eds. Ann Arbor, University of MichiganPress. 21. Marital fertility varied considerably in Europe, for example, with Ig's ranging from .65 to 1.00 even before systematic decline occurred (Coale 1969). Davis, Kingsleyand Judith Blake 1956 Social structure and fertility: an analytic framework. Economic Development and Cultural Change 4:211-35. 22. Ilocanos began colonizing the Cagayan Valley in large numbers in the second half of the 19th century. By 1903 one in five persons in the region was Ilocano. Since 1948, two of every three persons in the region Dixon, Ruth B. 1971 Explainingcross-cultural variations in age at marriage and proportions never marrying. Population Studies 25(2):215-33. • ., ' • REGIONAL AND PROVINCIAL DIFFERENTIALS IN MARRIAGE AND FAMILY BUILDING Duncan, Otis Dudley 1966 Path analysis: sociological examples. American Journal of Sociology 72(1): 116. Fennessey, James 1968 The general linear model: a new perspective on some familiar topics. American Journal of Sociology 74(1): 1-27. Goode, William J. 1963 World revolution and family patterns. New York, The Free Press. Hajnal, John 1953 Age at marriage and proportions marrying. Population Studies 7:111-36. 1965 ,, , • Henry, L. 1961 European marriage patterns in perspective. In Population in history. D. V. Glass and D. E. C. Everseley, eds. Chicago, Aldine Publishing Company. Some Data on Natural Fertility. Eugenics Quarterly 8:81-91. Keesing, Felix M. 1962 The ethnohistory of northern Luzon. Stanford, Stanford University Press. Lorimer, Frank W. 1966 Analysis and projections of the population of the Philippines. In First conference on population, 1965. Quezon City, University of the Philippines Press. Madigan, Francis C. 1965 Some recent vital rates and trends in the Philippines: estimates and evaluation. Demography 2:309-316. 181 Pascual, Elvira M. 1965 Population redistribution in the Philippines. University of the Philippines, Population Institute, Manila. 1971 Differential fertility in the Philippines. Unpublished Ph. D. Dissertation: Department of Sociology, University of Chicago. Regudo, Adriana C. 1965a Fertility patterns of ever-married women in the Ilocos, Central Luzon, and Bicol regions, 1960. Unpublished M. A. Thesis. Statistical Center, University of the Philippines. 1965b The effect of age at marriage on the fertility of ever-married women in the Ilocos, Central Luzon, and Bicol regions, 1960. The Philippine Statistician 4:265-81. Suits, Daniel B. 1957 The use of dummy variables in regression equations. Journal of the American Statistical Association 52:548-51. Taeuber, Irene B. 1960 The bases of a population problem: the Philippines. Population Index 26:97114. Tioleco, Alfonso 1970 A statistical technique for physical planning. Unpublished M. A. Thesis. Statistical Center, University of the Philippines. Vandemeer, Canute 1967 Population patterns on the island of Cebu, the Philippines: 1500 to 1900. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 57:315-37. SMITH, PETER C. 1971. Philippine regional and provincial differentials in marriage and family building: 1960. Philippine Sociological Review 19(3-4):159-81. PHILIPPINE SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW 182 • Percentage Distribution of Annual Household Income t Within Four Major Regions of the Phi1ippines t as of MaYt 1968* ...... ....tll til aJ ~ Annual Income c:; 10< ...... c~ tll~ 0 aJ C tll 10< S,2:i: Less than 125O 499 I 250 999 I 500 1 t999 II tOOO 12 tOOO 2 t999 13 tOOO 3 t999 14 tOOO 4 t999 15 tOOO or more Total Median Income .Cl, aJ tll 1.52% 2.44% 4.05% 17.32% 26.10% 13.60% 10.05% 24.92% ~ ~ ~'.J 6.67% 9.76% 21.88% . 30.14% 13.90% 7.27% 3.13% 7.25% to tll· 0 tll C c ~ 0. ~ ....tll ....0. ~ E-<ll.l 9.63% 15.98% 32.54% 23.93% 8.52% 4.70% 1.32% 3.88% 10.24% 14.86% 21.78% 30.87% 9.04% 4.42%. 1.43% 7.36% 7.69% 11.77% 23.12% 27.37% 12.63% 6.60% 2.95% 7.87% ~ :>.. tll s to ~ > .. ~ ~ o..c: :100.00% 100.00% 100.00% :100.00% 100.00% 1 P2 t950 Pl t400 I 850 lIt 100 PI t250 ~ Ratio of Observed Percentage ~ith a Given Income to that Expected if There Were No Regional Differences in Income.* • ...... ....tll ~ Annual Income 10< ...... c~ <lI~ 0 * Source: til <lI :>.. <lI to 10< tll t.?~ ~ ~ ~'.J > .20 .21 .18 .63 2.07 2.06 3.41 3.17 .87 .83 .95 1.10 1.10 1.10 1.06 .92 1.25 1.36 1.41 .87 .67 .71 .45 .49 aJ C Less than 1250 499 R 250 999 I 500 PltOOO 1 t999 12 tOOO 2 t999 13 tOOO 3 t999 14 tOOO 4 t999 15 tOOO or more C tll aJ <lI ~ 0 <lI C ~ C ~ ~ 1.33 1.26 .94 1.13 .72 .67 .48 .94 MaYt 1968 National Demographic SurveYt Excludes households giving no response to income question. .... ~