read essay - ADR Resources

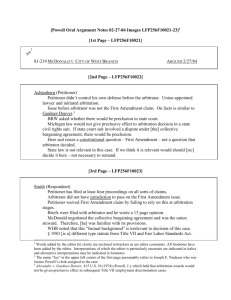

advertisement