Food taxes and their impact on competitiveness in the agri

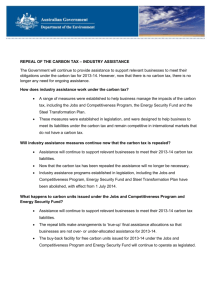

advertisement