1 CITY UNIVERSITY OF HONG KONG Misrepresentation Refer to

advertisement

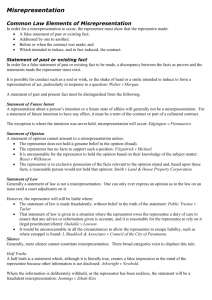

CITY UNIVERSITY OF HONG KONG Misrepresentation Refer to Richards Law of Contract Chapter 9 and Stone The Modern Law of Contract Chapter 10 A INTRODUCTION Historically, there has never been a general duty to disclose information during precontractual negotiations. But misrepresentations of various kinds do attract potential legal consequences. Professor Atyiah: The Rise and Fall of the Freedom of Contract: The older notion that a man could say what he liked to a prospective contracting party, so long as he refrained from positively dishonest assertions of fact seems to have come up against a new morality in the late nineteenth century. The courts began to insist on the duty of a party not to mislead the other party by extravagant or unjustified assertions … in their determination to stamp out laxer business morality. B WHAT IS A MISREPRESENTATION? “A false statement of fact that does not become a term of the contract, made either before or at the time of the making of the contract by one party to the other which induces that other to enter into the contract.” NB (it means to note) If the statement became a term of the contract, then a remedy will lie under the auspices of breach of contract. For example: X sells his house to Y. During the negotiations X deliberately hides the fact that there is a serious defect in the house. If Y discovers this after buying the house, he can have a remedy for misrepresentation. See Gordon v Selico Co Ltd [1986], the deliberate concealment of a defect in the house was a fraud on the part of the seller. 1 Representation Must be in the Form of a Statement A statement can be oral and express or, alternatively, it may be implied through conduct. 1 Gordon v Selico (1986) 278 EG 53 2 Non-Disclosure as Misrepresentation Failure to disclose a fact does not, without more, amount to a misrepresentation. For there is no general duty to disclose. Turner v Green [1895] 2 Ch 205 A half-truth is regarded in law as a misrepresentation. Dimmock v Hallett (1866) 2 Ch App 21 Nottinghamshire Patent Brick & Tile Co v Butler (1886) 16 QBD 778 3 Change of Circumstances as Misrepresentation If there is a change of circumstances between the making of a statement which was (believed to be) true at the time of its making and the time at which the contract was concluded, a failure to tell the representee of the change in circumstances renders the initial statement a misrepresentation. With v O’Flanagan [1936] Ch 575 The same rule applies where A represents something which he believes to be true at the time, but later discovers to be false. Davies v London and Provincial Marine Insurance Company (1878) 8 Ch D 469 4 There Must be a Statement of Fact The statement must be one of past or existing fact, and not one of intention, opinion or law. (a) Opinion versus Fact The general position is that an innocent statement of opinion is not capable of being an actionable misrepresentation. Bisset v Wilkinson [1927] AC 177 By contrast, where the representor has no basis for a statement of his opinion, but is in a position of superior knowledge by comparison with the representee, a statement of opinion is imputed to carry with it a statement of fact (i.e., a factual basis for the opinion expressed). 2 Smith v Land and House Property Corp (1884) 28 Ch D 7 (b) Intention versus Fact If it can be shown that as a matter of fact, the representor does not hold the intention that he expresses himself to hold, the representee can sue on the basis that it is factually untrue that the representor holds the intention he projects himself to hold. Edgington v Fitzmaurice (1885) 29 Ch D 459 The reasoning in this case was based on the notion that a statement of intention carries with it a statement of fact as to the current state of the representor’s mind. (c) Misrepresentation versus `Sales Talk’ Mere ‘sales talk’ has long been recognised not to constitute a representation for the purposes of the law of misrepresentation. Scott v Hanson (1829) 1 Russ & M 128 Cf (it means confer) Lord Brooke v Rounthwaite (1846) 5 Hare 298 C THE NEED FOR INDUCEMENT For the misrepresentation to be actionable, there must have been a material reliance on the misrepresentation by the representee. Thus, there can have been no inducement in three circumstances: 1 Claimant Never Knew of the Misrepresentation The claimant must normally show that he relied on the misrepresentation. If he fails to do so, his action will fail. Horsfall v Thomas (1862) 1 H & C 90 2 Claimant did not Allow the Misrepresentation to Affect his Judgement If the defendant can prove that there was no reliance, no action will lie for misrepresentation. 3 Attwood v Small (1836) 6 Cl & F 232 3 Claimant was Aware of the Falsity of the Representation It is clear that an inducement is to be construed objectively, rather than subjectively. Museprime Properties Ltd v Adhill Properties Ltd [1990] 2 EGLR 196 Redgrave v Hurd (1881) 20 Ch D 1 4 Partial Inducement Sufficient It is well established that the misrepresentation need not be the only reason for the representee contracting. Edgington v Fitzmaurice (1885) 29 Ch D 459 D FOUR KINDS OF MISREPRESENTATION 1 Fraudulent The classic definition of fraud is that supplied by Lord Herschell: [It is a false statement] made (1) knowingly, or (2) without belief in its truth, or (3) recklessly careless whether it be true or false. [Derry v Peek (1889) 14 App Cas 337] The real gist of fraud is dishonesty, the absence of belief in the truth of the statement on the part of the maker of the statement. 2 Negligent Until Hedley Byrne v Heller [1963] 2 All ER 575, all non-fraudulent misrepresentations were classed together as innocent misrepresentations. And there is nothing in the Hedley Byrne principle that prevents its application to a pre-contractual scenario. Esso v Mardon [1976] QB 801 3 A “section 2(1)” Misrepresentation The Misrepresentation Act 1967, s 2(1) states: Where a person has entered into a contract after a misrepresentation has been made to him by another party thereto and as a result thereof he has suffered loss, then, if the person making the misrepresentation would be liable to damages in respect thereof had the misrepresentation been made fraudulently, then the person shall be so liable notwithstanding that the misrepresentation was not made fraudulently, unless he proves 4 that he had reasonable ground to believe and did believe up to the time the contract was made that the facts represented were true. A key difference between section 2(1) and the common law is the reversal of the normal burden of proof. Howard Marine and Dredging Co v Ogden & Sons [1978] QB 574 Notwithstanding the `claimant-friendly’ reversal of the burden of proof, there remain three circumstances in which the claimant may still prefer to sue at common law. • where there is a potential difficulty in demonstrating that there has been a misrepresentation in its strict sense (see above); • where the rules on remoteness of damage favour an action in negligence (see below); • where the statement would also render the contract void for mistake since the Act requires the representation to induce a contract to be entered into (mistake not on the course). Criminal liability: Jail penalty for flat sellers who lie. Despite the reversed burden of proof under section 2(1), conviction on fraudulent misrepresentations in the property market has been rare. Law reformers are now calling for stiffer legislations. Property development staff and directors can face up to seven years’ imprisonment if they were found to have given false or misleading information, verbally or in writing, to boost sales or prices. The legislation is still proceeding which will posit curbs to the unscrupulous practice in the property market. 4 Innocent Misrepresentations Self explanatory: in essence, none of the three foregoing. E WHAT IS NOT A MISREPRESENTATION? The misrepresentation is a statement of existing fact or past event; The following cannot be misrepresentations: statement of law; statement of opinion. F REMEDY There are two remedies for misrepresentation: the right to rescind the contract; damages. Dr Eric Cheng City University of Hong Kong 10 January 2014 5