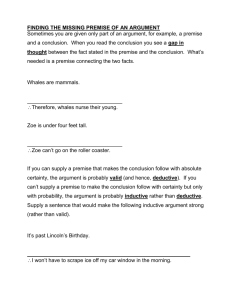

1 Chapter 1 - Premise / Ultimate Conclusion

advertisement