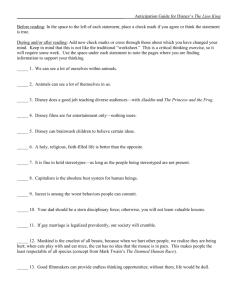

The Portrayal of Gender in the Feature

advertisement