Approaches to Textbook Affordability

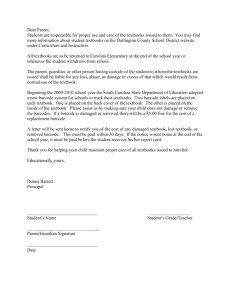

advertisement