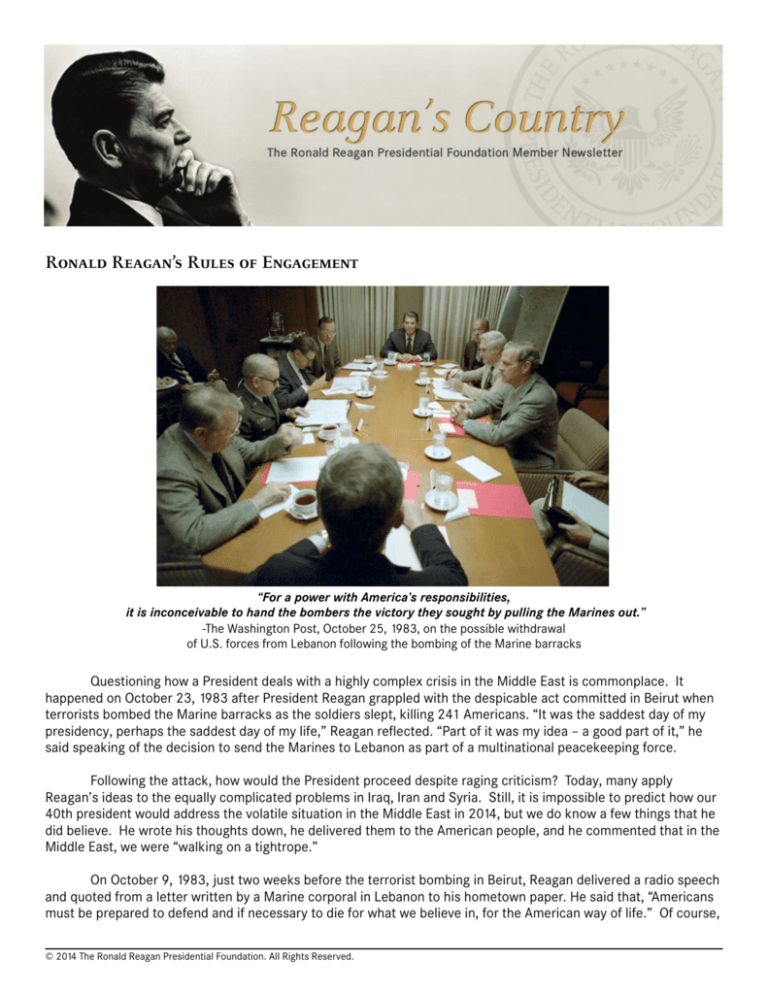

Ronald Reagan’s Rules of Engagement

“For a power with America’s responsibilities,

it is inconceivable to hand the bombers the victory they sought by pulling the Marines out.”

-The Washington Post, October 25, 1983, on the possible withdrawal

of U.S. forces from Lebanon following the bombing of the Marine barracks

Questioning how a President deals with a highly complex crisis in the Middle East is commonplace. It

happened on October 23, 1983 after President Reagan grappled with the despicable act committed in Beirut when

terrorists bombed the Marine barracks as the soldiers slept, killing 241 Americans. “It was the saddest day of my

presidency, perhaps the saddest day of my life,” Reagan reflected. “Part of it was my idea – a good part of it,” he

said speaking of the decision to send the Marines to Lebanon as part of a multinational peacekeeping force.

Following the attack, how would the President proceed despite raging criticism? Today, many apply

Reagan’s ideas to the equally complicated problems in Iraq, Iran and Syria. Still, it is impossible to predict how our

40th president would address the volatile situation in the Middle East in 2014, but we do know a few things that he

did believe. He wrote his thoughts down, he delivered them to the American people, and he commented that in the

Middle East, we were “walking on a tightrope.”

On October 9, 1983, just two weeks before the terrorist bombing in Beirut, Reagan delivered a radio speech

and quoted from a letter written by a Marine corporal in Lebanon to his hometown paper. He said that, “Americans

must be prepared to defend and if necessary to die for what we believe in, for the American way of life.” Of course,

© 2014 The Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation. All Rights Reserved.

when reading the letter, Reagan had no idea what was to occur in Beirut. Once it happened, he did not want

America to surrender to their killers.

Before dawn in Beirut on the morning of October 23, 1983, a truck carrying some 2,000 pounds of

explosives crashed through a series of barriers at the Marine Corps barracks, where our marines were sleeping and

instantly exploded. More than 200 of the sleeping men were killed in that one hideous, insane attack. This was not

the end of the horror. At almost the same instant, another vehicle on a suicide and murder mission crashed into

the headquarters of the French peacekeeping force, killing more than 50 French soldiers.

Upon arriving on the south grounds of the White House, Reagan spoke to the press briefly, saying that there

were no words to “express our sorrow and grief over the loss of those splendid young men and the injury to so

many others.” He paused and concluded, “but I think we should all recognize that these deeds make so evident the

bestial nature of those who would assume power if they could have their way and drive us out of that area, that we

must be more determined than ever that they cannot take over that vital and strategic part of the earth or, for that

matter, any other part of the earth.”

Now what? A great debate ensued because the cause of Lebanon had never been supported by the

President’s generals or by his Secretary of Defense.

Over the next 3 1/2 months, our soldiers in Lebanon withdrew, a process to which Secretary Shultz

vehemently objected. “We are in Lebanon,” he said, “because the outcome in Lebanon will affect our position in the

whole Middle East…to ask why Lebanon is important is to ask why the whole Middle East is important – because

the answer is the same.”

Secretary of Defense Cap Weinberger had a completely different perspective, believing that Lebanon was

hopeless and that the Marines had no useful purpose there. During a conversation Weinberger had with General

Colin Powell, he said, “I wished I had been more persuasive with the President.”

All conflicts aside, finding solutions to Middle East conflicts has never been a unilateral process.

In 1983, President Reagan and his advisors discussed whether to put the surviving Marines on ships or give

them a more defensible perimeter by expanding the territory they held. And if they chose the former and moved

Marines to the Mediterranean, it meant that dreaded word: withdrawal.

From the Oval Office, the president explained the scope of the problem:

“Let me ask those who say we should get out of Lebanon: If we were to leave Lebanon now, what message

would that send to those who foment instability and terrorism? If America were to walk away from Lebanon, what

chance would there be for a negotiated settlement, producing a unified democratic Lebanon?”

He continued, “If we turned our backs on Lebanon now, what would be the future of Israel? At stake is the

fate of only the second Arab country to negotiate a major agreement with Israel...”

While the President initially wanted action after the terrorist bombings in Beirut, Secretary of State Shultz

changed his position and remarked, “If I ever say send in the Marines again, somebody shoot me.” Reluctantly,

the President agreed with his team’s recommendation that the marines be “redeployed” to navy ships offshore.

In Reagan’s heart, he equated this “redeployment” with withdrawal, but ordered a review of policy in National

Security Decision Directive 111 (NSDD 111) which began a new era of strategic cooperation. NSDD 111 has been

declassified and you can read it by clicking here:

He went further. He asked for a set of principles to guide America in the application of military

force abroad and wrote about it in his memoirs. These, then, are the main principles, in his words, which he

recommended for use by future American presidents:

© 2014 The Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation. All Rights Reserved.

1. The United States should not commit its forces to military action overseas unless the cause is

vital to our national interest.

2. If the decision is made to commit our forces to combat abroad, it must be done with the clear

intent and support needed to win. It should not be a halfway or tentative commitment and there

must be clearly defined and realistic objectives.

3. Before we commit our troops to combat, there must be reasonable assurance that the cause

we are fighting for and the actions we take will have the support of the American people and

Congress (We all felt that the Vietnam War had turned into such a tragedy because military

action had been undertaken without sufficient assurances that the American people were

behind it.)

4. Even after all these other tests are met, our troops should be committed to combat abroad only

as a last resort when no other choice is available.

How do we apply these principles today? It’s not easy for any American president. Teddy

Roosevelt charted a more muscular role for the United States, advocating “speak softly but carry a big stick.”

Woodrow Wilson believed the United States could shape an effective peace settlement, outlined in his “Fourteen

Points” as he pursued changing course from isolation toward engagement. FDR issued a stern warning in 1942

regarding the violation of the Geneva Convention of 1925, which effectively produced an international agreement

on the rules of engagement in war. “We shall be prepared to enforce complete retribution,” he said.

In December 1985, once the Marines were safely out of Lebanon, President Reagan said “They are our

brothers…and we owe them our help…” President Reagan told us, “We cannot turn away from them, for the struggle

here is not right versus left; it is right versus wrong.”

© 2014 The Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation. All Rights Reserved.