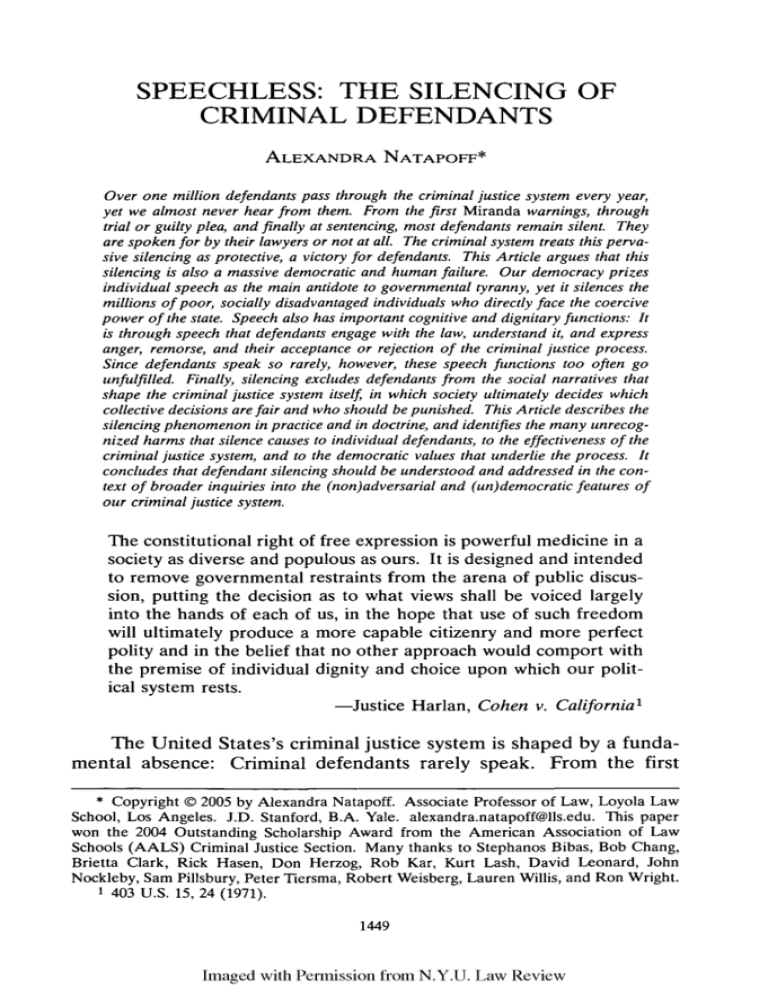

The Silencing of Criminal Defendants

advertisement