The Post-Marcos Presidency in “Political Time”

advertisement

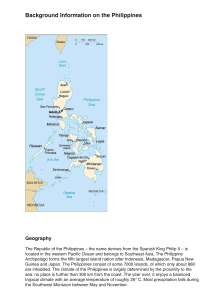

東南亞研究中心 Southeast Asia Research Centre Mark R. THOMPSON Director Southeast Asia Research Centre (SEARC) Professor of Politics Department of Asian and International Studies (AIS) City University of Hong Kong Hong Kong SAR The Post-Marcos Presidency in “Political Time” Working Paper Series No. 142 March 2013 The Southeast Asia Research Centre (SEARC) of the City University of Hong Kong publishes SEARC Working Papers Series electronically © Copyright is held by the author or authors each Working Paper. SEARC Working Papers cannot be republished, reprinted, or reproduced in any format without the permission of the papers author or authors. Note: The views expressed in each paper are those of the author or authors of the paper. They do not represent the views of the Southeast Asia Research Centre, its Management Committee, or the City University of Hong Kong. Southeast Asia Research Centre Management Committee Professor Mark R. Thompson, Director Dr Kyaw Yin Hlaing, Associate Director Dr Chiara Formichi Dr Nicholas Thomas Dr Bill Taylor Editor of the SEARC Working Paper Series Professor Mark R. Thompson Southeast Asia Research Centre The City University of Hong Kong 83 Tat Chee Avenue Kowloon Tong, Hong Kong SAR Tel: (852 3442 6330 Fax: (852) 3442 0103 http://www.cityu.edu.hk/searc The Post-Marcos Presidency in “Political Time” by Mark R Thompson, City University of Hong Kong Paper prepared for presentation at the Philippine Political Studies Association (PPSA) 2013 International Conference, Mariano Marcos State University (MMSU), 11-12 April 2013, Batac, Philippines, Plenary Panel 5 (This paper is part of a book project co-authored with Julio C Teehankee) The Philippine presidency, the oldest in Asia, has been the subject of remarkably little political science analysis. While there have been many biographies and journalistic accounts of Philippine presidents, there have been few studies of the presidency as an institution (among the few exceptions are Cortes, 1966; Bacungan, 1983, Agpalo, 1996a & b, Rebullida, 2006a&b, and Kasuya, 2008). This is surprising because in the Philippines, like in many presidential democracies in developing countries, the presidency is extraordinarily powerful, the keystone of the democratic system.1 But it has also been a system under threat. In the Philippine case, President Ferdinand E. Marcos, declared martial law in 1972: this autogolpe brought about the collapse of an electoral democracy that had been in place since independence in 1946 (and a presidential system begun during the Commonwealth period beginning in 1935). In the postMarcos era, the presidency has seemingly became a force for democratization (Rebullida 2006). But democratic transition in the Philippines has been very rocky, with presidents threatened by military plots, civilian protests, and civilian-initiated coups when facing legitimacy crises (Ronas 2011). By applying Stephen Skrowronek’s (1997; 2008) influential theory of U.S. presidentialism to the Philippines, this paper aims to show the usefulness of analyzing the 1 In fact, the Philippines appears to have one of the most powerful presidential systems anywhere in the world. Emil P. Bolongaita, Jr. (1995, p. 110) argues that “among presidential democracies, the Philippine president virtually has no equal in terms of aggregate executive power.” The president controls the bureaucracy and policy execution (including the use of executive orders) and also has the power of budget making and implementation (de Dios 1999; de Dios and Esfahani 2001). The presidency was marginally stronger under the 1935 Commonwealth than under the 1987 post-Marcos constitution, particularly due to limitations placed on emergency powers and the single term limit under the newer constitution. Both changes can be seen as being driven by fears of presidential abuse of power given the country’s authoritarian experience under martial rule. But surprisingly presidential powers remained otherwise strong, perhaps because legislators had little input into the writing of both constitutions (Kasuya, 2008, p. 86). Southeast Asia Research Centre Working Paper Series, No. 142, 2013 1 Philippine presidency in “political time” while offering insights that aim to advance the comparative study of the presidency. From this perspective, presidential performance is relational, with presidential agency confronting structural constraints and opportunities (Liebermann 2000). To give it a Marxian phrasing, presidents make their own presidencies, but they do not make it as they please. Presidents find themselves facing different obstacles to leadership based on their relation to a dominant “regime” (a stable set of interests, ideologies, and institutions that form around the presidency in a particular time period) established by a “foundationalist” president who usurps the pre-existing presidential order. In the U.S. context, Skowronek argues the current political regime of “small government” began during the Reagan presidency which repudiated the “liberal” New Deal-style regime started by Franklin Roosevelt in the 1930s of which Jimmy Carter was the last representative (Skowronek 2008, p. 19) In the Philippines, Corazon C. Aquino, after replacing the fallen dictator Marcos, “repudiated” Marcos’ failed “developmentalist” regime and installed a “reformist” one instead. Sequentially based challenges are understood by Skowronek as “political” as opposed to normal “secular” time. Applying the concept of “political time” - which is “reset” when a new regime is established – this paper will discuss the cycle of presidential leadership within the context of the post-Marcos “reformist” regime in the Philippines. Specifically, it will delineate the series of discrete political choices made by five post-Marcos presidents – Corazon C. Aquino, Fidel V. Ramos, Joseph E. Estrada, Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, and Benigno S. Aquino III – within the context of political time dictated by the character of this political order. “Reformism” in this context has involved a discursive commitment to combatting corruption in the name of good governance that binds together three key elite strategic groups (big business, the Catholic Church hierarchy, and middle class activists) within weak state institutions. Each post-Marcos president has been sequenced in political time based on this regime: Cory Aquino as regime founder, Ramos carrying the regime forward as an “orthodox innovator,” Joseph Estrada attempting but failing to “pre-empt” the regime with a “populist” platform (he was unconstitutionally removed from office), Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo as an “apostate” of the regime after she was seen as having betrayed her promised commitment to reform, and the current president as of this writing Benigno Simeon Aquino, III (“Nonoy”) who is again seen as a standard bearer of reformism. This brief summary of the post-Marcos presidencies suggest perceptions of presidential Southeast Asia Research Centre Working Paper Series, No. 142, 2013 2 performance are shaped by the sequencing of a particular presidency within the political “regime.” But this is not to say that agency has no role in this structuralist approach. By looking for a pattern of presidential “regimes” and the cycle of presidents within the political time set by these regimes, this perspective allows a fairer judgment of the choices president make because it takes into account structural constraints within which they choose. Consequently, the agentialstructural dichotomy underscores the “antinomies of presidential power recapitulate a more general dilemma in the social sciences, between structure and agency— between more or less deterministic patterns of social reality and the creative potential of individual human actors” (Lieberman, 2000, p. 275). By adopting a “structuration” approach as proposed by Anthony Giddens (1984) in this paper, due attention is given to both perspectives, agential and structural. The nature of presidential power in the Philippines will be analyzed by identifying the strategic moments that lie between the structural (regimes) and the agential (presidents’ choices). Finally, by arguing that a focus on campaign “narratives,” governing “scripts” and legitimacy crises sharpen the understanding of regimes in comparative perspective. Skowronek’s more conventional focus on ideas goes “too far” in the Philippine context in which diffuse campaign narratives and governing scripts lack a systematic, programmatic quality. In the Philippines context a regime can be understood as based not a series of more-or-less systematic ideas but as a diffuse governing “script” (that usually arises out of a campaign “narrative”) which binds together a coalition of interests within a particular institutional context. A Philippine presidential regime is not highly ideological in the sense Reagan and his Bush family dynastic successors in the U.S. have been, but rather is based on a certain set of mentalities that has characterized the reformism of Cory Aquino and her successor “reformist” presidents. On the other hand, in the context of a stable, long consolidated democracy like the U.S. political crises are unlikely to threaten the political system itself. Well established institutions seem capable of withstanding a series of political crises including a stolen election in 2000 and the current deadlock between Obama and the Republican controlled House of Representatives. In the Philippines, by contrast, severe legitimacy crises led to the overthrow of one president (Estrada) and nearly toppled a second (Arroyo). In the Philippine context, the presidency is a fragile institution that is under threat when a president loses legitimation. The consolidation of the U.S. system has concealed this problem to American observers of the presidency: the Southeast Asia Research Centre Working Paper Series, No. 142, 2013 3 institutional fragility of a regime can mean crises can soon cast into doubt the legitimacy of the political system itself. As is common in U.S. presidential studies, many scholars of the Philippine presidency emphasize the so-called “presidential style” of leadership that is understood within a particular cultural context (although in studies of the U.S. presidency the peculiarities of American political culture tend to be taken only implicitly into account rather than systematically analyzed). From an agential approach, presidents draw from an arsenal of political skills and character attributes to persuade others to do their bidding. In the Philippines, two viewpoints can be identified within this school of thought. One, a “decisionist” perspective, suggests that an effective president in the context of hierarchical Philippine culture must be a “strong” leader, which Remigio E. Agpalo - the Richard E. Neustadt (1991) of the study of the Philippine presidency - terms a “pangulo regime,” as will be discussed below. The other viewpoint is that the president must lead by example by being a “good” person within a folk cultural context. Regardless of whether the emphasis is put on “decisiveness” or “morality,” presidents hold their own fate in their hands if they are only “strong” or “good” enough while serving as the country’s chief executive. Other scholars view the Philippine presidency through the lens of political clientelism and patronage.2 In this school, the personal qualities of a president are secondary to her or his “role” (or even “function”) as “patron-in-chief”. Given the extraordinary powers the Philippine president possesses over the budget and the extensiveness of clientelist relations in Philippine politics, it follows from this viewpoint that the Philippine president is little more than a dispenser of patronage, a task that most presidents perform well enough (although there the occasional patronage-distribution-challenged president as we will see below). The next section discusses this patronage politics as a structuralist perspective before turning to agency-centered arguments about the importance of presidential character in understanding the chief executive’s performance in office. It will then be suggested that the political time approach combines a more plausible account of structural constraints and opportunities for presidential agency than either the determinist “patron-in-chief” or the voluntarist “presidential style” perspective. 2 Scholars sometimes try to distinguish clientelism, patron-client ties, and patronage, which they confine to the distribution of government “goodies” (jobs, contracts, etc). For a recent discussion, see Tomsa and Ufen 2012, pp. 4-5. Putting aside the linguistic overlap of the two terms (what do patrons do if not distribute patronage?), government patronage is the keystone of the clientelist system. Political patrons are exchanging “their” clientelist voting networks for something which can be nothing other than governmental patronage (by an incumbent) or promised patronage (by a candidate). Southeast Asia Research Centre Working Paper Series, No. 142, 2013 4 The president as patron-in-chief One important reason for the academic neglect of the Philippine presidency is the continuing dominance of the patron-client framework in the study of country’s politics, which has recently been supplemented by arguments about “bossism” which is not as distinct from clientelism as its proponents often contend.3 From this perspective, politicians are elected through long lines of clientelist ties that pyramid upward from voters to local and then to national politicians (Lande 1966, Kerkvliet 1995). Post-Marcos presidential candidates have generally founded their own parties (and/or party alliances), revealing only too clearly how “parties” are mere vehicles for a president’s election. “Political machinery” is assembled around the country needed for effective national “campaigning”. In short, parties in the Philippines are little more than a means to patronage-building necessary for a successful run for the presidency and then distribution of the perks of office to one’s clientelist allies once in power (Quimpo 2009). Changes in the 1987 constitution accelerated this process. While presidential candidates frequently changed parties in the pre-martial law Philippines, they generally did not found parties for their own presidential campaigns (and when they did they were transient third parties). With the opening of the electoral system to any group that declared itself a political party, a “multiparty” system was created in which most parties had a clear link to a particular presidential candidate and generally withered away or at least sharply decline after electoral victory or defeat (Magno 2006). Presidents may be at the top of the clientelist pyramid, but their ability to exercise power effectively rests on their skill in allocating patronage within this personalistic system. In the US and other developed country presidencies, presidents are said to represent national policies (in the language of rational choice theory, “collective goods”) while the legislature is concerned with local programs (pork barrel is used as a “selective incentive” by 3 “Bossist” (Rocamora 1995, Sidel 1999) analyses emphasize the role of coercion in relations between poor voters and political leaders which was missing from Lande’s original analysis in which the smooth functioning of clientelist ties between consenting poor clients and paternalist leader patrons was stressed. While this critique obviously has some validity (as the Ampatuan and other warlord clans have so violently demonstrated), it does not logically lead to the wholesale rejection of the clientelist framework as Sidel claims (1999), but rather points to the need to expand its scope. It remains unproven how widespread “bossism” really is in the Philippines until a detailed “political mapping “of the country is undertaken. Viewed more broadly, both votes secured through “consensual” ties between patrons and clients and more coercive relationships can viewed as “command” votes (Teehankee 2002). The former are votes controlled by political leaders either through personalized or material (and usually a mixture of both) ties of politicians to voters, the latter are votes “commanded” through the use of force. Southeast Asia Research Centre Working Paper Series, No. 142, 2013 5 legislatures to voters in order to secure re-election4). But in a highly clientelist system such as the Philippines, presidents may also be tempted to distribute “pork” to create majorities on key votes and to insure his or her own re-election. The presidency can even become a “fountain[head] of clientelist linkage building” (Kitschelt 2000, p. 860). Reducible to its “function” within a patronclient system, focus on the presidency as an institution appears to be of little independent interest. Furthermore, as there are no fundamental differences of ideology between the two parties: a party does not have a real “platform” or represent any major policy alternatives. In fact, according to Carl Lande’s “classical” clientelist theory of the Philippines (Lande 1967), “the leaders of each party are united by little more than their common desire to be elected,” thus making it unsurprising that they have no real party platforms. Furthermore, given that parties attempt to construct multi-class, multi-regional clientelist electoral alliances, too much emphasis on divisive political and social issues could potentially undermine a party’s electoral strength. Lande says that each major presidential candidate does have a “personal” platform, but this is also of limited significance.5 A president’s program is of little elite political or public concern. Lande writes: “Each new President, before he assumes office, or sometimes after that event, formulates a program for his administration which may be somewhat different from that of his predecessor. He devises this program in accordance with his personal convictions, and the advice of his principal lieutenants in the Executive branch and in Congress, usually staying within the fairly narrow limits set by the expectations of various organized and unorganized interests which no President can ignore. His ability to enact his program is limited not only by his uncertain control over his party — mates in Congress but also by the occasional indiscipline of the members of his Cabinet and their subordinates, as well as by a lack of public interest in and support for presidential programs as such. Typically, the election of a new President is followed by lively and protracted journalistic speculation concerning the names of possible cabinet appointees and by an almost total 4 “Pork” can be understand as political useful government-funded projects that are often economically inefficient (Kasuya 2008, p. 71). 5 When president do have pet programs still they have to “buy” support by the “distribution of favors” through patronage allocation. Southeast Asia Research Centre Working Paper Series, No. 142, 2013 6 lack of interest in, or discussion of, the President elect's legislative program” (Lande 1967, p. 35). In short, the clientelist perspective suggests that once in office presidents cannot rely on their electoral mandate or ideological commitments to rule effectively. Instead, presidents must use patronage as a tool to influence legislators in order to maintain power. Writing within this framework, Kasuya (2003, 2005 and 2008) argues that Joseph E. Estrada was impeached by the House of Representatives in November 2000 because he lost control of presidential patronage with which the president can normally can control (or at least contain) the lower house. She finds that Estrada lost the support of legislators who had received less patronage in the past and expected to receive less than others in the lower house in the future. Kasuya allows nonclientelist elements into her analysis in that she admits that Estrada’s “serious wrongdoings” were the catalyst for defections. But she emphasizes not everyone defected, just the weakest links in the clientelist chain: those party-switching legislators (known in the Philippines as “political butterflies” or “balimbings” from the many sided starfruit) who received less patronage from Estrada because they joined his camp later and also therefore expected less in the future from him, making their political defection less painful in patronage terms. The bottom line remains that according to this clientelist framework presidential “performance” is largely dependent on president’s effective wielding of patronage. Should s/he not live up to the role as “patron-in-chief” removal from office may be the result, as Estrada’s experience showed. The clientelist paradigm of the Philippine presidency is not so much wrong as it is one sided. It ignores evidence that most votes are now “market” ones open to direct media appeals to voters by candidates, not “commanded” by provincial bosses and/or leaders of clientelist networks (Teehankee 2002). Presidents must have a convincing campaign “narrative” in order to win office. Corazon C. Aquino was clearly “outgunned”, “outgunned” and “outgold” by incumbent Ferdindand E. Marcos in the 1986 “snap” presidential elections, yet some observers believe she actually won the election (even if she lost the counting) (de Guzman and Tancangco, 1986; NAMFREL 1986 and Thompson 1995, chp. 8). Presidential candidates with strong political machinery but with weak direct media appeals have been decisively defeated in almost all post-Marcos presidential elections (Ramon Mitra in 1992, Jose de Vencia in 1998, Manuel Villar in 2010). The exception is Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, who used all the patronage available to an incumbent president to win the 2004 elections. (Incumbents running for re-election was not Southeast Asia Research Centre Working Paper Series, No. 142, 2013 7 foreseen in the 1987 constitution that limited president’s to one term; Arroyo circumvented this by running again after a truncated first term after Estrada was toppled.) While her advantage in government patronage she used to cement clientelist ties clearly strengthened her election effort, the appeal of her “populist” opponent Fernando Poe, Jr., who had limited clientelist support and much less campaign money to spend that Arroyo, was still so strong that Arroyo had to engage in fraudulent electoral tactics that were later exposed that her opponents said she actually “stole” the election and used this to demonize during her remaining time in office (Raquiza 2005). Even “victorious” presidential candidates discovered the limitation of clientelist/bossist electioneering. In a study of the 1992 presidential election, Carl Lande (1996) partially relativized his earlier findings about the clientelist nature of Philippine politics. He pointed out that the candidate with the most money to spend and the strongest political machine (which he measured through the numbers of successful provincial political leaders each candidate had as allies), Ramon Mitra, did not win the 2004 election, and in fact only finished a distant fourth. The winner, Fidel V. Ramos, had less than half as many elected governors, representatives in the lower house, and Senators as Mitra did (60 to Mitra’s 129). Ramos also reportedly spent much less on his campaign than Mitra, although doubts have been raised about this claim given that he had the incumbent Cory Aquino’s endorsement (Lande 2006, pp. 106 and 109). The second placer in the 2004 election, Miriam Defensor-Santiago had almost no political machinery whatsoever measured in these terms. She is said to have spent only a miniscule percentage of what Mitra and Ramos did, yet she was defeated by Ramos by less than four percentage points (Mitra was nearly 10% behind Ramos). Lande then cited interviews with politicians who agreed that the country is no longer as feudal as in the past. Leaders can no longer deliver their constituents blindly. There must be some favorable perception by your constituents about the candidate. The media, especially radio, now provide a means by which voters can evaluate a national candidate (Lande 1996, p. 107). This paper draws on this insight. Successful presidential candidates need strong narratives that appeal directly to voters through media-driven campaigns. While not elaborate ideologies, they are not reducible to instrumental clientelist ties to voters and fellow politicians either. Once in office, presidents attempt to use their narrative as governing “scripts” both to maintain popularity and maintain elite support. The interests behind a presidency are not Southeast Asia Research Centre Working Paper Series, No. 142, 2013 8 reducible to the distribution of political patronage, but involve popular appeals and the support of key “strategic groups” who have not just material but also ideational reasons to support or oppose particular presidents. Institutional arrangements and the degree of their stability are of particular importance given the way “disloyal oppositionists” make extra-constitutional efforts to subvert the presidency. While Kasuya’s clientelist-style analysis provides some insight into Estrada’s impeachment by the lower house, it cannot explain what triggered it (“outrage” at Estrada’s corruption), nor does it tell us how Estrada actually lost power. He was not of course convicted by the Senate (where Estrada’s patronage power was stronger?) but rather was forced out of office by a “people power coup” in which elite demonstrators backed by the military made Estrada give in. In terms of the analysis offered here, Estrada had lost the support of the “(un)holy” trinity of big business, the Catholic Church hierarchy and middle class activists. This also lies outside the clientelist framework, which focuses on clientelist ties of rich patrons to poor voters not on elites angry with a sitting president. Despite being overthrown in an elitist insurrection, Estrada continued to enjoy strong support among the poor. Even after his long house arrest and conviction for corruption, many poor voters continued to back him, as his second place finish in the 2010 presidential election demonstrates. His successor Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo was a clear “master” of clientelist politics, but even that was not enough to stop the “FPJ” populist juggernaut in 2004 which is apparently why she turned to electoral manipulation to insure her “victory” in that election. Arroyo, however, paid for her electoral wrongdoings (and corruption scandals) in terms of popularity. Arroyo was the most hated president since Marcos as opinion polls showed (Wilson 2010). Yet she clung to power because two of the country’s three strategic groups, big business and the Catholic Church hierarchy, supported her despite vehement middle class activist opposition. Estrada was a “failed” president both in clientelist terms and for losing the support of the key elite strategic groups but retained strong support in the masa, among poor Filipinos. A broader form of analysis is needed to capture both the elite and popular dimensions of presidential “performance.” Presidential “style”: character and performance If the clientelist perspective is overly determinist, the chief alternative used by other scholars is highly volunterist. This influential perspective on the Philippine presidency – which is common in the analysis of presidential democracies including the US - is that a president’s Southeast Asia Research Centre Working Paper Series, No. 142, 2013 9 “character” is crucial in determining presidential performance (in the U.S. case Neustadt 1990 has been very influential). The problem of course is deciding which kind of character traits are favorable for good presidential performance, and what traits are seen to undermine such achievements. Given the personalistic nature of this perspective, an unending list of traits could be compiled by which to judge presidential conduct. In the Philippine context, I think it fair to single out two perspectives that are (or at least once were) influential: Remigio Agpalo’s “pangulo regime” (1996) and arguments centered around Catholic folk culture associated with the work of Reynaldo Ileto (1979 and 1985). Agpalo (1996) distinguished the character of Philippine leaders, and presidents in particular, through their ideological commitments and organizational capabilities. Strong Supremo-style presidents (a presidential type Agpalo models on Filipino revolutionary leader Andres Bonifacio) have both strong programmatic beliefs and extensive organizational support. For Agpalo, among recent Philippine presidents, Ferdinand E. Marcos fits this category best. Marcos strongly believed that the Philippine society was weakened by its oligarchical structure and was determined to use all the powers of government to transform it into a “new society”. He controlled, and enjoyed the strong of backing of the country’s bureaucracy. Although Agpalo’s argument may sound a bit like pro-Marcos propaganda, this conservative political scientist’s point of view deserves more serious attention than such a snap judgment would suggest. Even if Agpalo overlooks Marcos’ many character flaws and the fact that as a lawyer politician he not a military man on a mission to transform his country like Park Chung-hee was (Hutchcroft 2011), Marcos was nonetheless the most “developmentalist” president the Philippines has ever had. With the declaration of martial law and the launching of an export-oriented industrialization drive in the early 1970s, Marcos was attempting to put the Philippines on a path of authoritarian development well-trodden in Northeast Asia (in South Korea and Taiwan) but also by that point in Thailand (Sarit beginning in the late 1950s), in Singapore (Lee Kuan Yew and the People’s Action Party) and in Indonesia (Suharto beginning in the last 1960s). Such authoritarian developmentalism was subsequently undertaken by Mahathir in Malaysia as well (Suehiro 2008, chp. 5). It is beyond the scope of this paper to develop this argument in detail, but because of its developmentalist goals Marcos’ presidency has a different quality than his predecessors (and his Southeast Asia Research Centre Working Paper Series, No. 142, 2013 10 successors to date), not simply because of its authoritarianism, but also for its ideological and organizational commitment to transform the country economically and socially.6 It is not surprising that if Marcos was the ultimate Supremo for Agpalo, Corazon C. Aquino, appeared to be exact opposite. For Agpalo, she had neither clear ideological commitments nor strong organizational backing. A last minute compromise when the opposition was divided among several would be candidates to oppose Marcos in the February 1986 “snap” election, she ran under the banner of several opposition political parties and NGO-groups which often were conflict with one another (Agpalo, 1996, p. 261, Thompson, 1995, chp. 8). Aquino’s “rainbow coalition” as it was then called was expended further as assumed the presidency after the “people power” uprising against Marcos. She ruled over an (unruly) coalition that ranged from conservative to radical (or at least one-time radicals). Infighting quickly broke out among her political “allies,” explaining frequent demonstrations and coup attempts directed against her. Her government was largely “reactive,” striving largely survive and anyway having little vision of its own. If Marcos at least had started well (and clearly enjoyed some popular support during the early years of martial law), Aquino’s presidency began disastrously, with the biggest surprise being that she survived until the end of her term. The diametrically opposed view to Agpalo’s is a seemingly “yellow” one which takes into account Filipino folk Catholic traditions. Reynaldo Ileto famously argued that the pasyon (indigenous epic poems written under Spanish colonialism depicting the birth, life, and death of Christ in a didactic manner) by Filipino revolutionaries as powerful political metaphors used 6 This is a seemingly obvious point that too few writers about the Philippines are willing concede, in part because a large literature has been written condemning Marcos as “crony-in-chief” (or “chief of the cronies”) and confining analysis of his presidency to extreme patrimonialism (or ‘sultanism’ to use the term this author employed in his earlier analysis of Marcos, Thompson 1995). Viewed this way, the Marcos presidency can be placed in the clientelist framework, albeit one of authoritarian patronage. This confuses in my (revisionist) view the lamentable outcome of the Marcos presidency – economic and political crisis – with the developmentalist intentions that accompanied the launching of his legal and then later authoritarian presidency. Marcos’s commitment to developmentalism was genuine, even if he did not grasp how extreme cronyism, at which he was also highly skilled, could undermine it, particularly if it did not involve performance criteria to maintain economic efficiency despite close state-business ties as was the case in South Korea under Park Chung-hee (Amsden 1992). One of the few authors who has given Marcos his due as a tragic figure (albeit in a rather cranky manner) is Lewis Gleeck’s 1987 book that is hardly read anymore (if it ever was). Another book worth considering in this regard is the Marcos apologia written by American journalist (and later wife of then Marcos Minister of Foreign Affairs, Carlos P. Romulo) Beth Day: The Philippines: Shattered Showcase of Democracy, 1974. Despite its tendentiousness, the book reminds us of some of the “revolutionary” developmentalist projects that Marcos was undertaking during the early martial law period. Then there are of course Marcos’ own (ghost-written) tracts such as Revolution from the Center (1978). What Philippine president will ever again make a claim as baroquely melodramatic as this? Southeast Asia Research Centre Working Paper Series, No. 142, 2013 11 against Spain and then the Americans. He later applied this analysis to the reaction to the Aquino assassination in 1983 (Ileto 1979 and 1985). Ileto argued that in the context of Philippine folk culture the Aquino assassination seemed “a familiar drama involving familiar themes.” Aquino was often compared to Jose Rizal, whose writings and execution in 1896 helped spark the Philippine revolution against Spain. After his death, many Filipinos even began comparing Aquino’s sufferings to Christ, a comparison earlier made between Rizal and the Christian savior. When Marcos denied responsibility for the Aquino assassination, Ileto reports that a common retort was “Pontius Pilate”. A grief stricken nation imbued folk religious qualities into its newest fallen hero (Thompson, 1995, p. 116). What does this have to do with the Philippine presidency? Folk religious imagery accompanied the campaign of Cory Aquino for the presidency. September 1985 had seen the start of the “Marian celebration” commemorating the two thousandth anniversary of the birth of the Virgin Mary. In his homily at the event’s start Manila Archbishop Jaime Cardinal Sin had warned against a “dying of hope” during the “dark days” facing the country since the Aquino assassination. Hundreds of thousands of Filipino mobbed Sin his is travels around the archipelago with a small statue of the so-called Weeping Madonna. An estimated 1.5 milion gathered for a final mass in Manila in December, probably the largest religious celebration in Philippine history. The same crowds that had mobbed Sin and the Weeping Madonna cam out to see the “Filipina Mary,” Cory Aquino. She based her campaign of the promise of moral renewal: “honesty, sincerity, simplicity and religious faith” as she put it. Her answer to the Philippines’ many problems was simply to restore democracy and establish good governance (Thompson, 1995, pp. 144-45). In such moralistic terms, the tables of presidential performance are turned. The Supremo becomes a demon (Marcos complained that Aquino’s campaign had tagged him as a “combination of Darth Vader, Machiavelli, Nero, Stalin, Pol Pot, and maybe even Satan himself”), and, to mix metaphors further, the lamb defeats the wolf. When framed by a “developmentalist” regime perspective, which Agpalo evidently took, Marcos once seemed a successful, if not the outstanding Philippine president. When this project came crashing down after the Aquino assassination, debt overload, and currency devalution, the reformist narrative’s portrayal of Marcos as a corrupt dictator quickly took hold. Agpalo’s positive analysis reminds us how easy it once seemed to view Marcos as the Philippines “greatest president” (a google Southeast Asia Research Centre Working Paper Series, No. 142, 2013 12 search still yields nearly six million results under this category). Now he is commonly viewed as the worst, and certainly the most corrupt (in 2004 Transparency International ranked him the world’s second most corrupt leader after Suharto). Nearly two decades after Marcos’ fall from power, Arroyo was judged by the “yellow” followers of Aquino to be nearly as evil as Marcos (the Marcos/Arroyo comparison was common). Estrada had earlier been tarred by his elite opponents for feathering his own (love) nests. By contrast, “Noynoy” Aquino, like Fidel V. Ramos, has earned “moral seal of approval” from the yellow crowd. If all the above discussion of presidential “style” seems quite subjective and arbitrary, then the nature of the critique of this perspective has already been advanced. How a president is judged in terms of performance depends very much on the expectations and perceptions of the observer. It can be asked, for example, why the corruption scandals that dogged the Ramos administration (such as the PEA-Amari deal) did not undermine his presidential narrative, while such illicit dealings under Estrada were seen as sufficient justification for overthrowing him extra-constitutionally under the guise of revived “people power”. Similarly, it can be queried why Nonoy Aquino’s popularity has been boosted by rapid economic growth thus far during his presidency (with the president claiming vindication for his slogan “good governance is good economics”), while high growth during the Arroyo era won her no popularity whatsoever (she was the least loved president in terms of opinion polls) and was seen to have occurred despite massive corruption. The point is simply that judgments about a president are not formed in a vacuum but according to a regime narrative and how it is applied to a particular presidency. Ramos’s self-proclaimed reformism made his presidency “teflon-like” in regard to corruption charges while Estrada, already widely tagged by the yellow crowd as a lazy buffoon with movie star appeal to the poor, could easily be tagged as corrupt in elite eyes. Arroyo had earned the scorn of middle class activists (many of whom has supported her extra-constitutional rise to the presidency and her re-election bid in 2004) and thus faced vehement criticism regardless of economic growth. What is needed then is a way to more systematically assessments of the construction and defense of presidential narratives and the ways presidents attempt to use these narrative in new innovative ways or try to pre-empt them with a counter narrative. Arroyo was the most unpopular president - seen to be the most corrupt since Marcos - because she abandoned any pretext to “reformist” intentions, but did so under pressure from the “populist threat” first Southeast Asia Research Centre Working Paper Series, No. 142, 2013 13 represented by Estrada and later by Estrada’s friend, the even more popular actor and politician, Ferdando Poe, Jr. Furthermore, we must distinguish between popular approval of a president (which in the Philippines of course means the backing of the poor) and support within the elite (which can be divided into three key strategic groups, the Church, big business, and middle class activists). Skowronek adapted Stephen Skowronek situates the presidency not according to personal traits and attributes, but rather on “the structural pattern of regime change and the cycle of presidents within regimes—a pattern of ‘political time.’” He traces recurring regime patterns in the presidency, placing individual presidents within the context of regimes or “the commitment of ideology and interest embodied in preexisting institutional arrangements” (Skowronek 2008). Except for rare opportunities in which the regime becomes ripe for reconstruction, a president ascends to power within a prevailing regime that largely shapes the perception of that administration. The political identity of an incumbent president is either affiliated or opposed to the prevailing regime. Moreover, the political opportunity (i.e. success or failure of presidential leadership) available to the incumbent president hinges on how resilient or vulnerable a prevailing regime is (a strong regime is good for affiliates, harsh on would be preemptors, the opposite holds true for a weakened order structured around particular interests, ideologies, and institutions). Skowronek has argued that regime orientations provide structured contexts for presidential leadership that are repeated within political time. Thus, presidential leadership is defined by one’s place in “political time” rather than by personal style or character in facing down a series of challenges. Political time “is the medium through which presidents encounter received commitments of ideology and interest and claim authority to intervene in their development.” Comparing presidents in different historical period according to parallel moments of political time would yield more similarities in leadership challenges than those presidents compared according to the regular sequential period of secular time. Presidents find themselves facing different obstacles to leadership based on their relation to existing “regimes” that may be the same or different from their predecessors or successors. The study of Philippine presidentialism can benefit from such a mode of analysis. But it requires a more nuanced approach to the relationship between presidential actors and regime structures in the spirit of Giddensonian structuration. Also, Skowronek’s specification of regime Southeast Asia Research Centre Working Paper Series, No. 142, 2013 14 “ideology” is vague and profits from greater attention to the details of media-driven campaign “narratives” and the governing “scripts” that develop out of them. If a dominant regime “script” is seen to be challenged or worse abandoned by a president, the result is a legitimacy crisis, an aspect of presidential which Skowronek, focused on the institutionally stable US case, overlooks. Robert Lieberman attempts to combine structural and agency approaches in his analysis of US presidentialism. He argues for an emphasis on “moments of structured choice, opportunities for strategic presidential action within structurally defined and delimited situations” (Lieberman, p. 275). In paper an attempt is to adopt such an approach that balance agential perspectives and structural limitations or opportunities. A “timely” approach How can the concept of “political time,” reset when a new regime is established and “ticking” according to each president’s relationship to it, be applied from the study of the oldest and one of the best institutionalized presidential systems in an industrialized country, the U.S., to a “third world” context of chronic instability and widespread poverty such as the Philippines? It is often argued in the literature that the logic (but not the systemic performance) of presidential systems is similar, in industrialized and developing countries alike (Cheibub 2006, Mainwaring and Shugart 1997). Usually this argument is made negatively: the result of the competing electoral legitimacy of the president and the legislature is gridlock, political crisis or, at worse, democratic breakdown during inflexible, fixed presidential terms (Linz 1990). Yet the presidentialism literature provides a methodological justification for trying to understand better how the presidency works in a comparative context. But comparison between the U.S. and Philippine case is not an “independent” one, given that the Philippine presidency was adapted during “colonial democracy” (Paredes 1989), making it in many ways, in terms of institutional design, a system, from the American perspective, made “in our image” (Karnow 1990), although as noted above with greater powers than its US counterpart. The way the presidency in the Philippines and the US work shed insight into how far key concepts developed to analyze the US presidency can “travel” in social science terms (Sartori 1970). But if we accept presidential systems have a similar political logic across cultures and levels of development, we can confront the determinism of the clientelist view of the Philippine presidency as well as the voluntarist perspective of those scholars that stress the importance of presidential style by adapting a relational approach to the presidency in the Philippines. Instead Southeast Asia Research Centre Working Paper Series, No. 142, 2013 15 of stressing party ideologies which are unquestionably weak in the Philippines (Manasca and Tan, 2005 and Hicken, 2009), the narratives of presidential campaigns come into focus. These narratives, which become presidential “scripts” when a president takes power, are either portrayed as compatible with the overall regime narrative, or are an effort to “pre-empt” it. In the post-Marcos Philippines, “reformism”, the claim that fighting corruption and improving the efficiency of governance is the chief executive’s most important mission, has been the dominant regime mentality (Thompson 2010). Cory Aquino was the first and “foundationalist” postMarcos president with this narrative and her successor Ramos, strengthened this narrative further in his role as “orthodox innovator” in Skowronek’s terms. Estrada, by contrast, tried to pre-empt reformism with his populist narrative – that the “people” were oppressed by a greedy elite. After Estrada’s unconstitutional overthrow in a “people power” coup, his vice president and successor, Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo reclaimed the reformist script, promising a return to good governance after Estrada’s debauched and iniquitious presidency in the eyes of the activist middle class, the Catholic Church hierarchy and big business. But discovery of electoral manipulation and a number of high profile scandals made Arroyo an “apostate” of reform, setting the stage for the renewed reformism of candidate and then president, Benigno Aquino, III. While skeptics will doubt the importance of such narratives, they are crucial “marketing tools” in understanding why certain candidates were successfully elected and why their presidencies were considered “successes” or “failures”. “Interests”, a second component of Skowronek’s understanding of a presidential regime, also need to be understood differently in the Philippines than the US. Given the fact that most of the population is poor and relatively powerless, “strategic groups” in the Philippines stand out more starkly than what C. Wright Mills once called “the power elite” in the US (Mills 1956). The focus on the Philippine presidency three strategic groups (big business, the Catholic Church hierarchy, middle class activists) or four if the military is counted. Three of these groups are officially outside the government, though they have close ties to the state and often the representatives of the first and third groups take high ranking positions in presidential cabinets. Business holds the key to successful economic development and its support is of obvious significance to a successful presidency. But major business leaders have usually proved “laggards” in political activism related to the presidency, for example being slow to turn against Estrada and only “abandoning” Arroyo for candidate Aquino when her presidency was nearing Southeast Asia Research Centre Working Paper Series, No. 142, 2013 16 its end. The Catholic Church hierarchy, politicized during the anti-Marcos struggle (Youngblood 1991; Barry 2006), has continued to exercise great influence in the post-Marcos period. It was a crucial ally in the anti-Estrada coalition, but did not abandon Arroyo when she faced growing middle class-led opposition, helping save her presidency (here a clientelist-style analysis may prove useful given allegations of Arroyo giving cash bribes and luxury vehicles to key bishops). In the second Aquino presidency the Catholic Church hierarchy has led a high profile campaign against a relatively tame “reproductive health” bill (which does not touch the absolute ban on abortion, only promoting sex education and contraceptive availability). While the church hierarchy has threatened Aquino for pushing and passing the bill with a withdrawal of support over this issue it has not really abandoned his presidency as it once did Estrada’s, despite some weak attempts to support “pro-life” candidates during the current mid-term congressional elections and more successful efforts to influence the Supreme Court. Middle class activists are the most volatile and easily mobilizable strategic group in the Philippines. Strong supporters of Cory Aquino and Ramos, they turned against Estrada after several major corruption scandals. After a brief political romance with Arroyo, they turned on her following scandals regarding electoral manipulation and major government projects like lovers scorned. But without major business, church, or military allies, their weakness was revealed as Arroyo was able to survive in power to the end of her term. But under the second Aquino administration they again have found (as of this writing) a president middle class activists strongly support. The military seems to be another key strategic group, particularly given its “fire power” and ability to overthrow a government single handedly, but this is often misleading. In the postMarcos period this has sometimes occurred through the military hierarchy (the withdrawal of top generals’ support for Estrada) or against the hierarchy (lower officer-led coup attempts against Cory Aquino or Gloria Macapagal Arroyo). But in the Philippine case, the military (and in many other cases as well) “military rebels” have worked closely with other groups to challenge unpopular regimes. For example, military rebel leaders were linked with Marcos loyalists or proEnrile forces during coup attempts against Cory Aquino (Tiglao et al 1990). The previously mentioned (unholy) trinity of the Church, business, and middle class activists took the initiative in “people power II” which the military hierarchy only gradually came to support (Lande 2001). Middle class activists worked with military rebels in the coup attempts against Arroyo (Walsh 2006). But when the three major strategic groups – big business, the Church, and activists – have Southeast Asia Research Centre Working Paper Series, No. 142, 2013 17 been lined up in favor of a regime, such as during Ramos’ presidency and now during the second Aquino presidency – all has been quiet on the military front. The final element of Skowronek’s presidential regime, political institutions, is hardest to conceptualize clearly in the Philippine case. While the US has a constitutional arrangement that, with minor modifications, spans over two centuries, the Philippines is a recently democratizing country. Though it has a long institutional record of presidentialism that can be traced backed to the Commonwealth era (and before that to the short-live Philippine Republic that began in 1899), the current national institutional set up of which the presidency is the cornerstone has been quite unstable, as coup attempts and “people power” coups suggest. Another important difference to the US system is the rarity of a conflict in the Philippines between the presidency and the legislature due to the prevalence of patronage (the failure of such patronage toward the end of Estrada’s presidency being a key exception). But courts, and particularly the Supreme Court, have increasingly stood in the way of presidential ambition. One notable case was the striking down of a president Arroyo’s initiative to negotiate peace with armed Muslim secessionists in Mindanao in 2008. More recently, the second Aquino administration has waged institutional war against the chief justice of the Supreme Court, who was a midnight appointee of his hated predecessor and who led the court in blocking key early Aquino administration initiatives. His removal by House impeachment and conviction at a Senate trial was precedent setting in Philippine politics. Recently the court has delayed the implementation of the Reproductive Health act, suggesting it remains the only significant institutional obstacles to Aquino’s presidency. In short, the Philippine presidency faces few institutional constraints under most circumstances (it is telling that even Estrada though demonized by his elite detractors could not be removed constitutionally from power). Conclusion This paper has argued that a president’s relationship to the existing presidential “regime” is crucial in understanding the perception of a particular presidency. The following categorization of the post-Marcos presidents according to this “timing” of their presidencies was offered: the clock was started by Cory Aquino as the regime founder; Estrada tried to pre-empt reformism with a populist narrative (and was driven from power by a “yellow mob” for his efforts); Arroyo was meant to be another reformist president, but turned out to be an “apostate” (largely due to the manipulations she undertook to defeat the populist challenge of Estrada and Southeast Asia Research Centre Working Paper Series, No. 142, 2013 18 then FPJ); the “orthodox innovators” of the reformist regime, to use Skowronek’s terminology, were Ramos and Nonoy Aquino - both made reformism the centerpiece of their narrative and established a reputation as “clean” presidents (even if it is probably undeserved). This kind of relational analysis helps solve some of the riddles of the post-Marcos presidency. In terms of the economy’s performance, Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo was perhaps the most successful president as economic growth and other indicators were highest during her presidency (BizNews 2009). Yet polls show she could not literally buy popularity – on the contrary, she was the most unpopular president since Marcos. Of course, advocates of the “presidential style” school would claim that she had made major errors in the political realm, which she surely did. But those errors were not necessarily greater than some of her predecessors or even her successors (corruption scandals, for example, have plagued all post-Marcos presidential administrations). But the perception of her presidency as measured by opinion polls was highly negative. Conversely, the presidential performance of Corazon C. Aquino both in economic terms (the lowest growth of any post-Marcos presidency) and politically (the greatest instability) was, in any reasonably objective terms, quite poor. Her popularity did sink during her presidency, but remained always remained positive, putting her performance slightly above Ramos’s and far above Arroyo’s (SWS 2009). In both the negative case of Arroyo (and one should add Estrada here who was one of the most widely attacked presidents for corruption), and the positive one of Cory Aquino, suggest “success” is less related to presidential style than it is to a presidency’s point in “political time.” “Cory” founded a new reformist political regime and enjoyed legitimation from being seen as the “Marcos slayer” and having started a new political order. Even though she was often a weak and indecisive leader, economic growth was slow or sometimes negative during her administration, there were corruption scandals involving her relatives and friends, and numerous coup attempts against her rule were launched, her taking power at the “beginning” of the current “reformist time” in the Philippines goes far to explaining her popularity throughout her time in office. Arroyo, by contrast, was an apostate to this reformist regime as she had resorted too much to patronage, bossism, and outright electoral manipulation to “win” re-election in 2004 (exposed in the “hello Garci” tapes that appeared to approve the administration’s collusion with notorious Mindanao warlords, the Ampatuans, in fixing voting in parts of Mindanao that may have proved decisive in her re-election). Although clearly an intelligent and decisive leader who presided over nearly 10 years of continuous high Southeast Asia Research Centre Working Paper Series, No. 142, 2013 19 economic growth, Arroyo was the most unpopular president because she was seen as “betraying” the reformist regime. This leads back to the clientelist view of the Philippine presidency. Being seen as too closely part of the (inherently corrupt by moralist standards), clientelist system can be very harmful to a president’s popularity, as we have seen in the case of Arroyo’s presidency. Presidential candidates perceived as “machine” politicians (Mitra, de Venecia, etc) also suffered severe electoral harm from it. While Arroyo may have been able to sufficiently manipulate the clientelist/bossist system to insure her “re-election” it was at the cost of her popularity. Political “machinery” was however not enough for candidates who had a better “image” with voters. Political marketing has no place in clientelist theory. But it is used by candidates when making their “narrative appeals” to voters. In the post-Marcos Philippines, an anti-corruption, “reformist” narrative and “populist,” pro-poor appeals have been the most effective ones. A strong narrative is the key to being elected president. Once in the presidency however, a president with a populist narrative that runs up against the established “reformist regime” faces great difficulties. It is in this structural context that the “failure” of the Estrada presidency can best be explained - Estrada was removed from office after mass middle class-led demonstrations, a military withdrawal of support and the Supreme Court’s legitimation of this unconstitutional transfer of power. The problem that the Estrada faced was not primarily his loss of control over the patronage system in Congress as has been argued; rather it was that his “populist” narrative aroused virulent opposition from the key strategic groups behind the reformist regime (big business, the Catholic Church hierarchy, and parts of the military). Using corruption as an excuse (corruption which was widespread in administrations before and after Estrada), a middleclass led “people power coup” removed Estrada from office and attempted to restore the reformist narrative to the presidency. But when Arroyo was seen to have betrayed this reformist legacy, Nonoy Aquino effectively used it as a foil to restore this good governance narrative. His thus far “popular” presidency (measured in opinion polling) has been “successful” not primarily because of the economy’s performance (which initially lagged behind Arroyo’s impressive macro-economic record) but because it has adopted the symbolism of “good governance” and demonstrated “good intentions” of undertaking political reform widely seen as appropriate to this existing regime formation. Southeast Asia Research Centre Working Paper Series, No. 142, 2013 20 Literature Agpalo, Remigio, 1996a, “The Philippine Executive,” in Remigio Agpalo, Adventures in Political Science (Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press), pp. 1-18 Agpalo, Regigio, 1996b, “Leadership and Types of Filipino Leaders: Focus on Ferdinand E. Marcos and Corazon C. Aquino,” in Remigio Agpalo, Adventures in Political Science (Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press), pp. 251-269. Amsden, Alice H., 1992, Asia’s Next Giant: South Korea and Late Industrialization (Oxford: Oxford University Press). Bacungan, Froilan, 1983. The Powers of the Philippine president. Quezon City: U.P Law Center. Barry, Coeli, 2006, “The Limits of Conservative Church Reformism in the Democratic Philippines,” in Tun-Jen Cheng and Deborah A. Brown, eds., Religious Organizations and Democratizations: Cases Studies from Contemporary Asia (Armonk: M.E. Sharpe). BizNews- Asia, “GMA’s Legacy: Economy, Infra, Integration,” no. 19 (2009). Bolongaita, Emil P., Jr., 1995, “Presidential versus Parliamentary Democracy,” Philippine Studies vol. 43, no. 1 (1995): 105–123. Cheibub, Jose Antonio, 2006, Presidentialism, Parliamentarism, and Democracy (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press). Cortes, Irene R., 1966, The Philippine presidency: A study of executive power (PhD thesis, College o Law, University of the Philippines). de Dios, Emanuel (1999) ‘Executive–legislative relations in the Philippines: continuity and change’, in Colin Barlow (ed.), Institutions and Economic Change in Southeast Asia, Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, pp. 132–49. de Dios, Emmanuel S and Esfahani, Hadi Slehi, 2001. “Centralization, Political Turnover, and Investment in the Philippines,” in J Edgardo Campos, ed., Corruption: the Boom and Bust of East Asia since the Asian Financial Crisis (Quezon City: University of Ateneo Press) De Guzman, Raul P and Tancangco, Luzviminda, An Assessment of the 1986 Special Presidential Elections: A Study of Political Change through People Power, vols. 1 and 2 (Manila: College of Public Administration, University of the Philippines). Southeast Asia Research Centre Working Paper Series, No. 142, 2013 21 Giddens, Anthony, 1984, The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration (Cambridge: Polity Press). Gleeck, Lewis E., Jr., 1987, President Marcos and Philippine Political Culture (Manila: published by the author). Hicken, Allen, 2009, Building Party Systems in Developing Democracies (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), p. 16. Hutchcroft, Paul D. and Rocamora, Joel, 2003, “Strong Demands and Weak Institutions: The Origins and Evolution of the Democratic Deficit in the Philippines,” Journal of East Asian Studies, vol. 3, no. 2 (May-August), pp. 259-292. Hutchcroft, Paul D., 2011, “Reflections on a Reverse image: South Korea under Park Jung Hee and the Philippines under Ferdinad Marcos,” in Byung-Kook Kim and Ezra F. Vogel, eds., The Park Chung Hee Era: The Transformation of South Korea (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press). Ileto, Reynaldo Clemeña, 1979, Pasyon and Revolution: Popular Movements in the Philippines, 1840-1910 (Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila) Ileto, Reynaldo, 1985 “The Past in the Present Crisis,” in R.J. May and Francisco Nemenzo, eds., The Philippines after Marcos (Sydney: Croom Helm) Karnow, Stanley, 1990, In Our Image: The American Empire in the Philippines (New York: Ballantine Books) Kasuya, Yuko, 2005, “Patronage of the past and future: Legislators' decision to impeach President Estrada of the Philippines,” The Pacific Review, 18:4, pp. 521-540 Kasuya, Yuko, 2008 Presidential Bandwagon: Parties and Party System in the Philippines (Tokyo: Keio University Press) Kasuya, Yuko, 2003, “Weak institutions and strong movements: the case of President Estrada’s impeachment and removal in the Philippines,’ in Jody Baumgartner and Naoko Kada (eds), Checking Executive Power: Presidential Impeachment in Comparative Perspective, Connecticut: Praeger, pp. 45–63. Kerkvliet, Benedict J. Tria,1995, “Toward a More Comprehensive Analysis of Philippine Politics: Beyond the Patron-Client, Factional Framework,” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 26 (2), pp. 401-419. Southeast Asia Research Centre Working Paper Series, No. 142, 2013 22 Kitschelt, Herbert, 2000, “Linkages between Citizens and Politicians in Democratic Polities,” Comparative Political Studies 2000 33: 845-879. Landé, Carl (1966) Leaders, Factions and Parties: The Structure of Philippine politics (New Haven: Southeast Asia Studies). Lande, Carl H., 1967, “The Philippine Political Party System,” Journal of Southeast Asian History, Volume 8, Issue 01 (March), pp 19-39 Lande, Carl H. 2001, “The Return of ‘People Power’ in the Philippines,” Journal of Democracy, 12, no. 2 (April) pp. 88-102. Lieberman, Robert C., 2000, “Political Time and Policy Coalitions: Structure and Agency in Presidential Power,” in Robert Y. Shapiro, Martha Joynt Kumar, and Lawrence R. Jacobs, Presidential Power: Forging the Presidency for the Twenty-First Century (New York: Columbia University Press) Linz, Juan J., 1990, “The Perils of Presidentialism,” The Journal of Democracy (Winter), pp. 51-69. Manasca, Rodelio Cruz Manacsa and Tan, Alexander, 2005, “Manufacturing Parties: Reexamining the Transient Nature of Philippine Political Parties,” Party Politics 11:6 (November), pp. 748–765. Mainwaring, Scott and Shugart, Matthew Soberg, 1997, Presidentialism and Democracy in Latin America (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press) Marcos, Ferdinand E, 1978, Revolution from the Center (Hong Kong: Raya Books). Malaya, J. Eduardo and Jonathan E. Malaya, 2005, So Help Us God; The Presidents of The Philippines and Their Inaugural Addresses (Manila: Anvil). Magno, Alex R., 2006, “Elections in a Depreciated Democracy,” I-Report, Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism, 6 December (http://pcij.org/stories/elections-in-adepreciated-democracy/; accessed 27 February 2013). Mills, C. Wright, 1956, The Power Elite (Oxford: Oxford University Press). NAMFREL (The National Citizens Movement for Free Elections), 1986, The NAMFREL Report on the February 7, 1986 Presidential Elections (Manila: no publisher). Neustadt, Richard E. 1991, Presidential Power and the Modern Presidents: The Politics of Leadership from Roosevelt to Reagan (New York: Free Press) Southeast Asia Research Centre Working Paper Series, No. 142, 2013 23 Paredes, Ruby R., 1989, Philippine Colonial Democracy (New Haven: Yale University Southeast Asian Studies). Quimpo, Nathan Gilbert, 2009, “The Philippines: Predatory Regime, Growing Authoritarian Features,” The Pacific Review, Vol. 22, Issue 3, 2009 Raquiza, Antoinette, 2004, “The proprietary presidency and the limits to Philippine democracy,” Kasarinlan: Philippine Journal of Third World Studies, volume 19 number 2, 2004 (http://fil-globalfellows.org/proprietaryprez.html, accessed 20 February 2013). Rebullida, Ma. Lourdes G. Genato, 2006a “Executive Power and Presidential Leadership: Philippine Revolution to Indepence,“ in Noel M. Morada and Teresa S. Encarnacion Tadem, eds, Philippine Politics and Governance: An Introduction (Quezon City: Department of Political Science, University of the Philippines), pp. 117-152. Rebullida, Ma. Lourdes G. Genato, 2006b “The Philippine Executive and Redemocratization,”in Noel M. Morada and Teresa S. Encarnacion Tadem, eds, Philippine Politics and Governance: An Introduction (Quezon City: Department of Political Science, University of the Philippines), pp. 179-216. Rocamora, Joel, 1995, “Classes, Bosses, Goons, and Guns: Re-lmagining Pbilippine Political Culture,” in Jose F Lacaba, ed., Boss: Five Studies of Local Politics in the Philippines (Quezon City: Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism, Institute for Popular Democracy). Ronas, Malaya C., 2011, “The Never Ending Democratization of the Philippines,” in Felipe B. Miranda, Temario C Rivera, Malay C. Ronas, and Ronald D. Holmes, Chasing the Wind: Assessing Philippine Democracy (Quezon City: Commission on Human Rights, Philippines), 99, 95-138 Sartori, Giovanni, 1970, “Concept Misformation in Comparative Politics,” The American Political Science Review, Vol. 64, No. 4 (Dec.), pp. 1033-1053. Sidel, John T., 1999, Capital, Coercion, Crime: Bossism in the Philippines (Stanford: Stanford University Press). Skowronek, Stephen, 1997, The Politics Presidents Make: Leadership from John Adams to Bill Clinton (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997) Skowronek, Stephen, 2008, Presidential Leadership in Political Time: Reprise and Reappraisal (Lawrence: Univ Suehiro, Akira. 2008. Catch-Up Industrialization: The Southeast Asia Research Centre Working Paper Series, No. 142, 2013 24 Trajectory and Prospects of East Asian Economics (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press), chp 5.ersity of Kansas Press) Social Weather Stations, 2009, “Net Satisfaction Ratings of Presidents from May 1986 to September 2009” (PolitEkon: October 2009politekon.blogspot.com, accessed 24 March 2013). Teehankee, Julio C., 2002, “Electoral Politics in the Philippines,” in Aurel Croissant, Gabriele Bruns and Merei John, eds., Electoral Politics in Southeast and East Asia (Singapore: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung), pp. 149-202. Thompson, Mark R., 1995, The Anti-Marcos Struggle: Personalistic Rule and Democratic Transition in the Philippines (New Haven: Yale University Press). Thompson, Mark R., 2010, “Reformism versus Populism in the Philippines,” Journal of Democracy, 21, no. 4 (October), pp. 154-168. Tiglao, Rigoberto, et al, 1990, Kudeta: The Challenge to Philippine Democracy (Quezon City: Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism). Tomsa, Dirk and Ufen, Andreas, 2012, “Introduction: Party Politics and Clientelism in Southeast Asia,” in Tomsa and Ufen, eds., Party Politics in Southeast Asia: Clientelism and Electoral Competition in Indonesia, Thailand and the Philippines (London: Routledge), pp, 1-19. Walsh, Bryan, 2006, “Inside the Philippines Coup Plot,” Time (Feb. 24) (http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1167191,00.html, accessed 23 March 2013). Youngblood, Robert, 1991, Marcos against the Church: Economic Development and Political Repression in the Philippines (Ithaca: Cornell University Press). Southeast Asia Research Centre Working Paper Series, No. 142, 2013 25