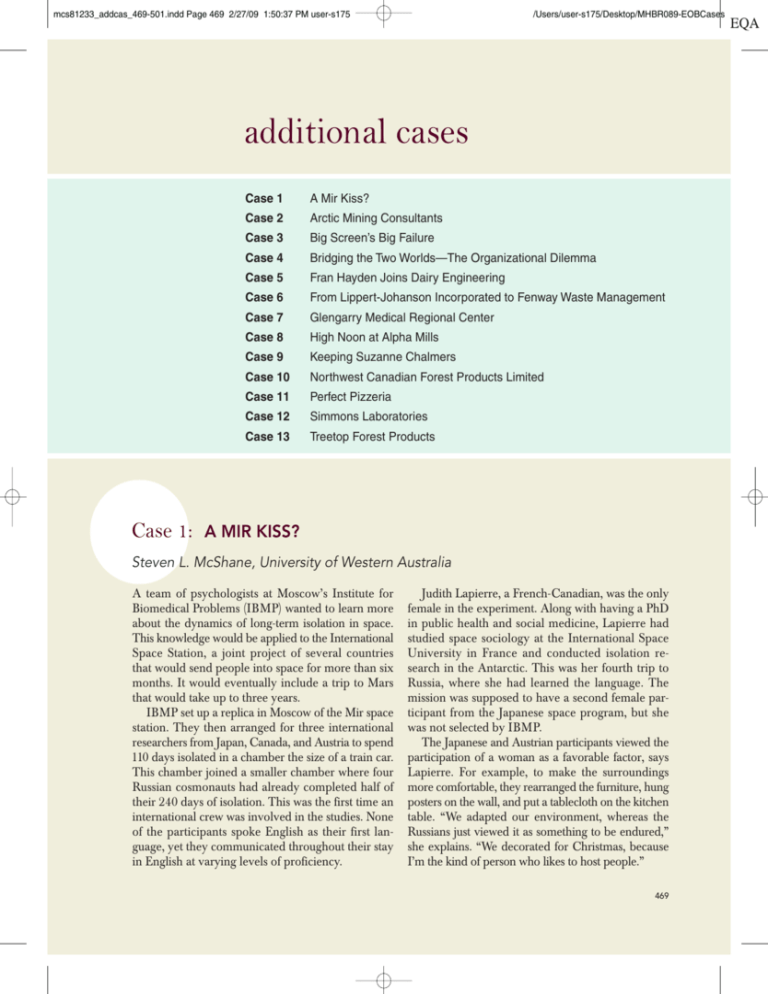

additional cases

advertisement

mcs81233_addcas_469-501.indd Page 469 2/27/09 1:50:37 PM user-s175 /Users/user-s175/Desktop/MHBR089-EOBCases additional cases Case 1: Case 1 A Mir Kiss? Case 2 Arctic Mining Consultants Case 3 Big Screen’s Big Failure Case 4 Bridging the Two Worlds—The Organizational Dilemma Case 5 Fran Hayden Joins Dairy Engineering Case 6 From Lippert-Johanson Incorporated to Fenway Waste Management Case 7 Glengarry Medical Regional Center Case 8 High Noon at Alpha Mills Case 9 Keeping Suzanne Chalmers Case 10 Northwest Canadian Forest Products Limited Case 11 Perfect Pizzeria Case 12 Simmons Laboratories Case 13 Treetop Forest Products A MIR KISS? Steven L. McShane, University of Western Australia A team of psychologists at Moscow’s Institute for Biomedical Problems (IBMP) wanted to learn more about the dynamics of long-term isolation in space. This knowledge would be applied to the International Space Station, a joint project of several countries that would send people into space for more than six months. It would eventually include a trip to Mars that would take up to three years. IBMP set up a replica in Moscow of the Mir space station. They then arranged for three international researchers from Japan, Canada, and Austria to spend 110 days isolated in a chamber the size of a train car. This chamber joined a smaller chamber where four Russian cosmonauts had already completed half of their 240 days of isolation. This was the first time an international crew was involved in the studies. None of the participants spoke English as their first language, yet they communicated throughout their stay in English at varying levels of proficiency. Judith Lapierre, a French-Canadian, was the only female in the experiment. Along with having a PhD in public health and social medicine, Lapierre had studied space sociology at the International Space University in France and conducted isolation research in the Antarctic. This was her fourth trip to Russia, where she had learned the language. The mission was supposed to have a second female participant from the Japanese space program, but she was not selected by IBMP. The Japanese and Austrian participants viewed the participation of a woman as a favorable factor, says Lapierre. For example, to make the surroundings more comfortable, they rearranged the furniture, hung posters on the wall, and put a tablecloth on the kitchen table. “We adapted our environment, whereas the Russians just viewed it as something to be endured,” she explains. “We decorated for Christmas, because I’m the kind of person who likes to host people.” 469 mcs81233_addcas_469-501.indd Page 470 2/27/09 1:50:38 PM user-s175 New Year’s Eve Turmoil Ironically, it was at one of those social events, the New Year’s Eve party, that events took a turn for the worse. After drinking vodka (allowed by the Russian space agency), two of the Russian cosmonauts got into a fistfight that left blood splattered on the chamber walls. At one point, a colleague hid the knives in the station’s kitchen because of fears that the two Russians were about to stab each other. The two cosmonauts, who generally did not get along, had to be restrained by other men. Soon after that brawl, the Russian commander grabbed Lapierre, dragged her out of view of the television monitoring cameras, and kissed her aggressively— twice. Lapierre fought him off, but the message didn’t register. He tried to kiss her again the next morning. The next day, the international crew complained to IBMP about the behavior of the Russian cosmonauts. The Russian institute apparently took no action against any of the aggressors. Instead, the institute’s psychologists replied that the incidents were part of the experiment. They wanted crew members to solve their personal problems with mature discussion, without asking for outside help. “You have to understand that Mir is an autonomous object, far away from anything,” Vadim Gushin, the IBMP psychologist in charge of the project, explained after the experiment ended in March. “If the crew can’t solve problems among themselves, they can’t work together.” Following IBMP’s response, the international crew wrote a scathing letter to the Russian institute and the space agencies involved in the experiment. “We had never expected such events to take place in a highly controlled scientific experiment where individuals go through a multistep selection process,” they wrote. “If we had known . . . we would not have joined it as subjects.” The letter also complained about IBMP’s response to their concerns. Informed of the New Year’s Eve incident, the Japanese space program convened an emergency meeting on January 2 to address the incidents. Soon after, the Japanese team member quit, apparently shocked by IBMP’s inaction. He was replaced with a Russian researcher on the international team. Ten days after the fight—a little over a month after the international team began the mission—the 470 /Users/user-s175/Desktop/MHBR089-EOBCases doors between the Russian and international crew’s chambers were barred at the request of the international research team. Lapierre later emphasized that this action was taken because of concerns about violence, not the incident involving her. A Stolen Kiss or Sexual Harassment? By the end of the experiment in March, news of the fistfight between the cosmonauts and the commander’s attempts to kiss Lapierre had reached the public. Russian scientists attempted to play down the kissing incident by saying that it was one fleeting kiss, a clash of cultures, and a female participant who was too emotional. “In the West, some kinds of kissing are regarded as sexual harassment. In our culture it’s nothing,” said Russian psychologist Vadim Gushin in one interview. In another interview, he explained: “The problem of sexual harassment is given a lot of attention in North America but less in Europe. In Russia it is even less of an issue, not because we are more or less moral than the rest of the world; we just have different priorities.” Judith Lapierre says the kissing incident was tolerable compared to this reaction from the Russian scientists who conducted the experiment. “They don’t get it at all,” she complains. “They don’t think anything is wrong. I’m more frustrated than ever. The worst thing is that they don’t realize it was wrong.” Norbert Kraft, the Austrian scientist on the international team, also disagreed with the Russian interpretation of events. “They’re trying to protect themselves,” he says. “They’re trying to put the fault on others. But this is not a cultural issue. If a woman doesn’t want to be kissed, it is not acceptable.” Sources: G. Sinclair, Jr., “If You Scream in Space, Does Anyone Hear?” Winnipeg Free Press, May 5, 2000, p. A4; S. Martin, “Reining in the Space Cowboys,” Globe & Mail, 19 April 2000, p. R1; M. Gray, “A Space Dream Sours,” Maclean’s, 17 April 2000, p. 26; E. Niiler, “In Search of the Perfect Astronaut,” Boston Globe, 4 April 2000, p. E4; J. Tracy, “110-Day Isolation Ends in Sullen . . . Isolation,” Moscow Times, 30 March 2000, p. 1; M. Warren, “A Mir Kiss?” Daily Telegraph (London), 30 March 2000, p. 22; G. York, “Canadian’s Harassment Complaint Scorned,” Globe & Mail, 25 March 2000, p. A2; and S. Nolen, “Lust in Space,” Globe & Mail, 24 March 2000, p. A3.