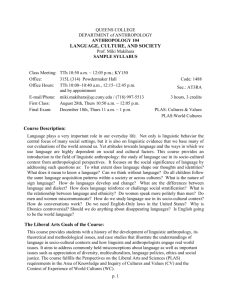

Salute to Scholars

advertisement