Variations in Minnesota Probation Services

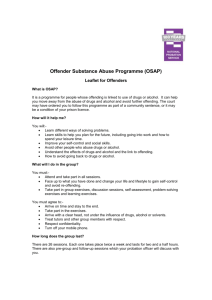

advertisement