Challenges for Career Interventions in Changing Contexts

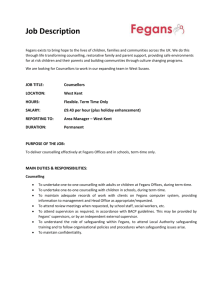

advertisement

International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance (2006) 6: 3–14 DOI 10.1007/s10775-006-0002-4 ÓSpringer 2006 Challenges for Career Interventions in Changing Contexts NORMAN AMUNDSON Faculty of Education, University of British Columbia, 2125 Main Mall, Vancouver, B.C., V6T 1Z4, Canada (E-mail: amundson@interchange.ubc.ca) Received: September 2005; Accepted: November 2005 Abstract. Current social and economic changes have created a challenging context for career counsellors. Within this context counsellors are being asked to view their role from different perspectives. There is recognition of the importance of lifelong guidance and also the need to view guidance from a broader social context with greater emphasis on social responsibility and ethics. New forms of delivery are also emerging. These include an emphasis on client centred and holistic counselling, an affirmation of narrative methods, and a more dynamic counselling approach. Lastly, there is the development of a number of new methods of service delivery. Some examples include one stop counselling centres, virtual counselling services, mentoring, career coaching, and the inclusion of social enterprises as part of the counselling process. The implementation of these changes has implications for training, specialization and for accreditation. Résumé. Défis pour les interventions d’orientation dans des contextes en mouvance. Les changements sociaux et économiques actuels ont créé un contexte qui constitue un défi pour les conseillers d’orientation. Dans ce contexte, on demande aux conseillers de concevoir leur rôle selon différentes perspectives. On reconnaı̂t l’importance de l’orientation tout au long de la vie ainsi que la nécessité de considérer l’orientation à partir d’une perspective sociale plus large avec un accent plus marqué sur la responsabilité et l’éthique sociales. De nouvelles formes de conseil sont aussi en émergence. On insiste sur une approche holistique et centrée sur le client, sur les méthodes narratives et sur un conseil plus dynamique. Enfin, on voit se développer un certain nombre de nouvelles méthodes concernant l’offre de services. A titre d’exemples, on peut citer les centres de conseil plateformeunique les services de consultation virtuels, le tutorat, le coaching de carrière et l’insertion dans des entreprises sociales en tant qu’élément du processus de conseil. La mise en oelig;uvre de ces changements a des implications pour la formation, la spécialisation et pour l’accréditation. Zusammenfassung. Herausforderungen an Hilfen zur Berufsentscheidung in veränderlichen Kontexten. Aktuelle soziale und ökonomische Veränderungen haben einen herausfordernden Kontext für Berufsberater geschaffen: In diesem Kontext sind die Berater aufgefordert, ihre Rolle aus verschiedenen Perspektiven zu betrachten. Die Bedeutung einer lebenslangen Beratung wird erkannt, und ebenso die Notwendigkeit, Beratung in einem erweiterten sozialen Zusammenhang unter größerer Betonung von sozialer Verantwortung und von ethischen Gesichtspunkten zu betrachten. Ebenso entstehen neue Formen der Hilfen zur Berufsentscheidung. Diese schließen eine Betonung der klientenzentrierten und ganzheitlichen Beratung ein, eine Bestätigung narrativer Methoden und einen dynamischeren Beratungsansatz. Schließlich findet auch eine Entwicklung neuer Angebotsformen statt. Einige Beispiele sind ganzheitliche (One-Stop) Beratungszentren, virtuelle Beratungsangebote, Mentoren- und Coachingangebote, sowie die Einbeziehung sozialer Institutionen in den Beratungsprozess. Die Umsetzung dieser Veränderungen hat Auswirkungen auf die Ausbildung, die Spezialisierung und die Berufszulassung von Berufsberatern. Resumen. Desafı́os para la Orientación Profesional en Contextos Cambiantes. Los cambios sociales y económicos actuales han generado un contexto desafiante para los orientadores de la carrera, a quienes se les pide contemplar su rol desde distintas perspectivas. Se reconoce la importancia de la orientación a lo largo de la vida y la necesidad de asumir la orientación desde un contexto social más amplio con mayor énfasis en la responsabilidad social y la ética. También están surgiendo nuevas formas de intervención. Entre éstas podemos destacar el énfasis en la orientación holı́stica y 4 NORMAN AMUNDSON centrada en el cliente, una defensa de métodos narrativos y un enfoque de la orientación más dinámico. Finalmente, se han desarrollado nuevos métodos para la provisión de servicios. Algunos ejemplos son los centros de orientación de ‘‘una parada’’, servicios virtuales, mentores, acompañamiento (coaching) y la inclusión de empresas sociales como parte del proceso de orientación. La realización de estos cambios tiene claras implicaciones para la formación, especialización y la acreditación. The rapid pace of social and economic change has contributed to the creation of a changing context for career counselling. The changes have been fuelled by increasing globalization, advances in technology and information, and significant demographic shifts (Homer-Dixon, 2000). The scale of change is of a magnitude that has forced people to critically reflect upon many underlying assumptions and of course this has relevance for the way in which career counselling practice is developing. Bloch (2005, p. 195) makes the following observation: In the late 20th century many supposedly immutable truths were thrown into question not by those who simply questioned the truths but by those who had gone beyond doubting the individual beliefs to doubting the very system of thought in which the beliefs were constructed. This somewhat chaotic environment has dramatically changed the nature of working life and a number of authors have documented these changes (Amundson, Jang, & To, 2004; Feller, 2003; Herr, 1999). The changes can be summarized as follows (Amundson, 2005): – Greater competition and pressure for productivity. – Less defined and predictable career pathways – both within organizations and in looking for work. – Organizational change being driven by mergers, joint ventures and work alliances. – More opportunities for work in different parts of the world. – Greater reliance on temporary or contract positions. – Greater need to consider self-employment options. – Increased diversity (racial, gender) in the workplace. – Greater emphasis on technological skills. – Increased need for skilled trades workers. – More tasks and greater work/life complexity. – More need for dual career planning/pressure on families. – Increased emphasis on interpersonal skills i.e., teamwork, networking. – Need for continuous learning. – Need for ongoing innovation. – Fewer opportunities for upward mobility. – Greater income disparity between workers and managers. These changes have had a great influence on people at all levels. Within the career counselling field the nature of clients has increased in complexity and in CHALLENGES FOR CAREER INTERVENTIONS 5 resistance levels. The client populations have become more diverse and multibarriered. There are demands for a greater range of services. Career counsellors are also expected to work with many clients who have been mandated to come for counselling. As counsellors attempt to work within this new more challenging environment they find that their funding is being reduced while expectations are rising. In many ways they are living the same reality as their clients. There are cutbacks to services, increasing reliance on short-term project based funding and expectations to do more with less. They are also dealing with a workplace with greater accountability and pressure for certification and ongoing skill development. This parallel process certainly leads to tension in the workplace and in some ways can reduce the level of quality service (Amundson, Borgen, Jordan, & Erlebach, 2004). A response to these types of challenges is required at both the policy and the career intervention level. The OECD has been involved in a major study to examine career counselling policies and practice. Watts (2003) has used the results from this study to comment on public policy development. There also has been the recent establishment of the International Centre for Career Development and Public Policy (ICCDPP). This new centre has developed some important recommendations for career counselling policy and practice. This paper will focus only on the changes in career intervention that are emerging as a response to the contextual challenges. While these changes in practice are important they are closely linked to practical and policy support for effective implementation. New perspectives Lifelong career guidance Given the ongoing nature of change there is a growing recognition that career choice and decision-making is a life long process. The idea of a lifetime job or even a lifetime profession is something that is changing. People can no longer depend on educational and work organizations to direct their career planning. There is an increasing focus on employability and ‘‘self-organizing’’ behaviour in response to career challenges. Career terms such as ‘‘boundaryless’’ (Arthur & Rousseau, 1996), ‘‘portfolio’’ (Handy, 1994), and ‘‘protean’’ (Hall, 1996) have been associated with this self-organizing ideal. This shift in focus implies a need for a different approach to career guidance. This new approach is one in which the functions of career guidance are stretched in several different directions. Firstly, there are many different groups of career guidance counsellors and they each have traditionally worked in isolation from one another. There are counsellors working in the schools, in post-secondary institutions, in employment agencies, with private and public organizations, and so on. Each group 6 NORMAN AMUNDSON has its own professional associations and there is very little overlap among the various groups. What is needed at a very basic level is greater integration and ‘‘fusion’’ of occupational and organizational guidance at both a theoretical and practical level (Amundson, Parker, & Arthur, 2002). Career guidance professionals need to expand their professional borders to include a lifelong career guidance perspective. If guidance is truly lifelong, then the next shift is to developmentally include activities, which build upon one another and can be employed over the life span. There is an old adage that states that if one ‘‘gives a person a fish they won’t be hungry for a day, teach them how to fish and they won’t be hungry for a life time.’’ In our current context we could probably add some further skills in addition to simply catching fish. The fish need to be caught in a sustainable manner and then there are the skills of packaging and marketing that also could be included. As an overview of this developmental process the Blueprint for Life/Work Designs (2005) provides a competency template for children, youth and adults. The Blueprint organizes career competencies into the following three broad areas: personal management, learning and work exploration and life/work building. It also offers information to organizations about the necessary levels of structure, support and commitment. As career counsellors seek to weave together career competencies through the lifespan they need to focus on helping people to identify and apply life/ career patterns. The term ‘‘psychological DNA’’ can be used when referring to these patterns and guidance exercises have been developed such as the pattern identification exercise to focus on the patterns (Amundson, 2003b). The pattern identification exercise involves an in-depth exploration, usually starting with interests and then expanding to include information related to values, skills, personal style and significant others. The analysis is collaborative and the focus is always on the ways in which patterns can be identified and applied across different aspects of life. Most people are surprised by the way in which an in-depth examination of an interest can lead to life/career patterns that play a role across all aspects of life. In addition to specific exercises, a wheel diagram that serves as a guiding framework to help people organize personal and labour market information has been used. This wheel has been adapted and incorporated into four career guidance workbooks: (1) Career Scope – youth (Amundson, Poehnell, & Pattern, 2005); (2) Career Pathways – adults (Amundson & Poehnell, 2003); (3) Career Exploration Handbook – Royal Canadian Mounted Police (Amundson & Poehnell, 2004); and (4) Guiding Circles – aboriginal youth and adults (McCormick, Amundson, & Poehnell, 2002). The wheel has proven itself to be a useful guidance tool for different ages and for different cultural groups. CHALLENGES FOR CAREER INTERVENTIONS 7 Social perspectives Many counsellors are becoming more aware of diversity issues and the fact that career guidance is more than just an individual enterprise. It is a project that calls for moral choices and the recognition that people always need to be understood within their social and cultural context (Thrift & Amundson, 2005). Guichard (2003) suggests that in this broader context the core question of career counselling can ‘‘no longer be centred around helping people achieve their own potential as independent individuals, but rather by helping people achieve their own humanity, through collectively helping others achieve their own humanity, each in his or her own way.’’ (p. 318). Rather than accepting all career choices as equally valid there is recognition of the need to place greater emphasis on the quality of career decisions that are being made (Cochran, 1997). Plant (1999) suggests that career decision-making needs to be framed within the context of ‘‘green guidance’’ where people are encouraged to critically think about the types of decisions that are being made. It is not just about getting a job, it is also a matter of reflecting upon what type of work one is doing. There are many issues to be considered here, Plant is particularly focused on the way in which work supports or undermines the physical environment. Several distinguished researchers in the U.S. have also raised the importance of contextual issues in making career choices. Gardner, Csikszentmihalyi, and Damon (2001) have focused their efforts on the ‘‘Good Work’’ project. The project focuses on ‘‘what it means to carry out ‘good work’ – work that is both excellent in quality and socially responsible – at a time of constant change’’ (p. ix). Good work brings harmony between excellent work and ethics. With this harmony come both personal and social rewards. New methods Client centred and holistic career counselling With all the demands and constraints in the counselling situation it is easy to lose sight of the need to develop and maintain a good counselling relationship. The research on counselling efficacy (Hackney & Cormier, 1996) points to the importance of the counselling relationship and the working alliance. All counselling interventions are dependent on the foundation of a good relationship. Building a relationship in career counselling means making every effort to see the whole person, not just the problems. With this broader view there is a growing awareness of the integration of the personal and the vocational domains (Bedi, 2004). Personal and contextual variables such as family, community, ecology, leisure and spirituality need to be taken into account when considering career issues (Amundson, 2003a; Hansen, 1996; Plant, 1999). 8 NORMAN AMUNDSON One way of addressing these various factors is through an exercise where people are asked to list all the things they enjoy doing (Amundson, 2003b). Once they have listed up to 20 different things there is a discussion of the items with particular reference to issues such as: when they last did the activity, costs, whether an activity was planned or spontaneous, whether they were alone or in a group, and the needs that were being fulfilled (mental, emotional, physical, spiritual). This simple exercise helps broaden the level of enquiry and serves as a good foundation for relationship building. In addition to discussion focused exercises there also is a need to attend to the degree of ‘‘mattering’’ that clients feel within counselling contexts. Mattering is the belief that clients hold about their significance in the counselling process (Connolly & Myers, 2003). Mattering is enhanced through our actions as well as through our words. Mattering is expressed in the way we greet clients, the way in which we relate to them during counselling sessions, and the way in which we follow-up with them afterwards. Narrative focused counselling methods In order to cope with increasing complexity in the workplace there is a need to move away from positivistic ideology toward a view of the person as a selfconceiving and self-organizing system (Cochran, 1997). Rather than trying to dissect and analyse all the pieces it is more prudent to try to capture the full narrative through the eyes of the person involved (Peavy, 2004). The focus here is on how people understand and make sense of their situation as told through their unique career stories. Savickas (2005) indicates that career counsellors using this method should encourage clients to tell stories about their work experiences. These stories help create a certain narrative truth about how people live their lives. In listening to the stories counsellors need to be aware of how the stories reflect various personality dimensions, life themes, and a general capacity for adapatability. Dynamic counselling methods As people try to navigate the many complexities of the current social and economic context they often are perplexed and feel ‘‘stuck,’’ uncertain of how to move forward. In some ways they suffer from a ‘‘crisis of imagination’’ (Amundson, 2003b). Dynamic counselling helps to reinvigorate the imagination by creating new possibilities and structures and by encouraging the use of multiple perspectives. Some of the changes in dynamic counselling focus on the use of different forms of physical space, more visual methods, different time frames, and more flexible interpersonal arrangements. There also is the use of a greater range of counselling methods, some of which include: focused questioning, metaphors, card sorts, mind mapping, values exercises, achievement profiling, walking the problem, task analysis, and so on (Amundson, 2003b). CHALLENGES FOR CAREER INTERVENTIONS 9 These dynamic methods fit well with paradoxical notions such as ‘‘positive uncertainty’’ (Gelatt, 1989) and ‘‘planned happenstance’’ (Mitchell, Levin, & Krumboltz, 1999). Rather than focusing on linear and ‘‘either-or’’ thinking there is the acceptance of ambivalence, intuition and flexibility and the recognition that in many instances problems need to be approached from a ‘‘both-and’’ perspective. Chaos theory also fits with this more dynamic approach. With chaos theory there is an emphasis on understanding how patterns and new forms of order emerge from environments where there is disorder and unpredictability (Bloch, 2005; Pryor & Bright, 2003). Pryor and Bright (2004, p. 2) indicate that ‘‘in human terms this equates ultimately to spiritual values such as purpose, meaning, balance, harmony, mission, commitment, contribution and integrity.’’ New forms of delivery Integrated one stop centres Organizational trends towards greater productivity through mergers, joint ventures and work alliances have also found a place in the delivery of career services. In the United States the Workforce Investment Act of 1998 helped to coordinate most federally funded employment and training services into a single system, called the one stop centre. These centres were designed to streamline services for jobseekers, engage the employer community, and build an infrastructure for service delivery. In a recent impact study, the initial results appeared promising (United States General Accounting Office, 2003). The centres were using cross training, special service training, collaboration and partnerships to offer more integrated services. The recommendation was for further studies focusing more specifically on job placement and job retention data. In discussing the efficacy of these one stop centres with counsellors at a recent conference there was an expression of enthusiasm for the process and the recognition that clients benefited through the more integrated system. At the same time, there was also an indication that there were some real challenges in merging the different services. Virtual career guidance Technology and information systems have become increasingly important in the new economy for productivity and for working with more complex systems. It is not surprising to see that information technology has become an integral part of most career guidance systems. According to Sampson (1999) the use of an integrated web site in a career centre can help to: (1) Provide educational and employment information; (2) Supplement some services such as resume writing, career exploration and assessment; (3) Provide up-to-date operational 10 NORMAN AMUNDSON information about the running of the centre; and (4) Provide links to commercial and non-commercial resources and services. Sampson et al. (2001) go on to illustrate how web-based guidance can be used to build a virtual guidance centre. The four components of such a centre are: links to existing websites, locally developed information, access to web counselling, and an overall monitoring function (Amundson, Harris-Bowlsbey, & Niles, 2005). Illustrations of centres where web based guidance is well integrated include the Florida State University site at http://www.career.fsu.edu and ReadyMinds (http://www.readyminds. com), a commercial site. In the U.K. there is Learn direct (http://www.learndirect.co.uk/home/), a virtual centre focusing on youth and adult learning. The receptivity of career practitioners toward internet based career guidance is something that remains an ongoing issue. Hambley and Magnusson (2001) conducted a study focusing on this question. Their results suggest that while practitioners were generally receptive to the internet they still had concerns about how to use the resource in a time efficient manner. Those practitioners that made the most use of the internet had a higher level of education and tended to use the Internet in their personal lives. They also found that for counsellors in rural setting the Internet was used more frequently. Brief counselling, mentorship and coaching The push towards greater efficiency and productivity has led to a growing interest in breaking down traditional career guidance into shorter and more accessible segments. In brief counselling, for example, there is an attempt to use a more intense and positively focused process with short-term goals. The intent is that small changes can lead to more broadly based results and that strength based guidance can have a significant impact (Friedman, 1993). Other developments have included the use of some career guidance activities under the framework of mentorship or career coaching. Initially this developed as a more facilitative way for managers and seasoned professionals to support the development and career choices of new employees (Randolph, 1981). Mentorship relationships and programs have continued to thrive in many different settings with most of the focus on the benefits of the mentorship relationship (Johnson, 2002). Workers today are being asked to work within organizations where there are less defined and predictable career pathways. They also need to form networks and to work collaboratively with others (teamwork). All of these factors help create a more challenging workplace. Having a good relationship with a mentor can be a valuable asset for integration and for movement within an organization. Career coaching has also enjoyed considerable success, likely for many of the same reasons as mentorship. Career coaches can provide some guidance for both movement within an organization and also for broader career development strategies. Coaches often operate from outside of the system and at times, this can CHALLENGES FOR CAREER INTERVENTIONS 11 be an advantage. The field of career coaching has grown rapidly and it has now developed its own professional group with specific practices and training programs. Career coaches tend to be more problem and task focused, they often operate outside of traditional counselling boundaries, and may assume a more active role in interacting with their clients. The main criticism has been the lack of standards with respect to professional and ethical issues (Chung & Gfroerer, 2003). Social enterprise: Counselling on the ‘‘fringe’’ The increasing number of multi-barriered and mandated clients has led to some real challenges for career counsellors. Many of the traditional intervention strategies are designed for a middle and upper class clientele. In working with a more challenging client group there is need for advocacy, innovation, and a more active stance. For some career counsellors this has meant the blending of a counselling model with a business model. The creation of ‘‘social enterprises’’ has become one of the ways of addressing the needs. Programs that seem to have some success are often small and operate outside the traditional boundaries of government funded agencies. For example, the Just Works program in Vancouver, Canada targets their career service to the needs of homeless people. They have established a drop-in pottery studio in a church basement (pottery is sold at local markets) as well as developed a painting business that pays people for every 15 min of work. At one point the government was interested in offering some funding to the program but program officers were unable to fit the program structure into existing funding formulas. So, the program continues with a ‘‘shoestring’’ budget and private donations. While the lack of government funding is a challenge, there also are some benefits. Many clients are wary of government services and are more receptive to programs where there is not a direct financial connection to the government. Implementation issues While there are many exciting new developments in career guidance with respect to perspectives, methods and forms of service, there also are some very real issues in terms of implementation. In order to operate within this more complex and challenging environment there is a need for training and for career specialization and accreditation. In Canada has been given attention since 1996 on the development of a national framework for career guidelines and standards. At the international level the recent creation of the International Centre for Career Development and Public Policy (ICCDPP) is one mechanism for continuing this effort toward standards and guidelines for career practice. Funding shortages also continue to be a problem and it is becoming increasingly important to answer the questions of some policy makers by 12 NORMAN AMUNDSON linking career practice with economic efficiency, social equity, and sustainability (Herr, 2003; Hiebert, 1994). While much of the existing research points to participant satisfaction there is a need for better research about the efficacy of career guidance methods and programs (Magnusson, 2004). The challenge here is to also develop research paradigms that are consistent with some of the new forms of career guidance practice. This requires innovation and greater collaboration between researchers and practitioners. Summary and conclusions Changing contexts have created challenges for career interventions but also new opportunities. The focus of counselling has broadened and people are now more willing to view guidance as a lifelong activity that has strong social and cultural influences. There is also recognition of the increasing complexity of career counselling. Personal and vocational issues are more integrated and more holistic. Dynamic counselling methods are being employed often within the context of the story. A number of different forms of delivery are being implemented. There are attempts to integrate services through one stop centres and virtual guidance is increasingly becoming a reality. Brief counselling is also becoming accepted and there are also increased utilization of mentorship and career coaching. At the other end of the spectrum, there are increasing number of multi-barriered clients and in some centres social enterprises are being developed to offer greater employment options. All these changes have implications for the training needs of counsellors. With the increase in complexity there is an obvious need for more training and for standards. There is also a need for greater resources to meet the growing demands. Looking ahead, what is emerging are two broad levels of concern. On the one hand, there are increasing demands for skilled labour and with the current demographic trends this should result in some shortages. At the same time, there also are many people who do not have the necessary skills. Thus, there is the emergence of both an employment and an unemployment problem. This presents some interesting challenges for career counsellors as they will need to learn to operate within both domains. To be effective in the 21st century career counsellors will need to expand both their thinking and their intervention repertoire. References Amundson, N.E. (1989). A Model of Individual Career Counseling. Journal of Employment Counseling, 26, 132–138. Amundson, N.E. (2003b). Active engagement: Enhancing the career counselling process. Richmond, B.C.: Ergon Communications. Amundson, N.E. (2005). The potential impact of global changes in work for career theory and practice. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 5, 91–99. CHALLENGES FOR CAREER INTERVENTIONS 13 Amundson, N.E., Borgen, W.A., Jordan, S., & Erlebach, A.C. (2004). Survivors of downsizing: Helpful and hindering experiences. The Career Development Quarterly, 52, 256–271. Amundson, N.E., Harris-Bowlsbey, J., & Niles, S. (2005). Essential elements of career counseling. Columbus, OH: Pearson Merill Prentice Hall. Amundson, N.E., Jang, A., & To, N. (2004). Trends in today’s Canada: Food for thought document number 12. Ottawa: Canadian Career Development Foundation. Amundson, N.E., Parker, P., & Arthur, M.B. (2002). Merging two worlds: Linking occupational and organizational career counselling. Australian Journal of Career Development, 11, 26–35. Amundson, N.E., & Poehnell, G. (2004). Career exploration handbook. Richmond, B.C.: Ergon Communications. Amundson, N.E., & Poehnell, G. (2003). Career pathways. Richmond, B.C.: Ergon Communications. Amundson, N.E., Poehnell, G., & Pattern, M. (2005). Career scope: Looking in, looking out, looking around. Richmond, B.C.: Ergon Communications. Arthur, M.B., & Rousseau, D.M. (1996). The boundaryless career: A new employment principle for a new organizational era. New York: Oxford University Press. Bedi, R.P. (2004). The therapeutic alliance and the interface of career counseling and personal counseling. Journal of Employment Counseling, 41, 126–135. Bloch, D.P. (2005). Complexity, chaos, and nonlinear dynamics: A new perspective on career development theory. The Career Development Quarterly, 53, 194–207. Blueprint for Life/Work Designs. (2005). What is the Blueprint? Retrieved June 11, 2005 from http://www.blueprint4life.ca/. Chung, Y.B., & Gfroerer, M.C.A. (2003). Career coaching: Practice, training, professional, and ethical issues. The Career Development Quarterly, 52, 141–152. Cochran, L. (1997). Career counseling: A narrative approach. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Connolly, K.M., & Myers, J.E. (2003). Wellness and mattering: The role of holistic factors in job satisfaction. Journal of Employment Counseling, 40, 152–160. Feller, R.W. (2003). Aligning school counseling, the changing workplace, and career development assumptions. Professional School Counseling, 6, 262–271. Friedman, S. (1993). The new language of change. New York: The Guilford Press. Gardner, H., Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Damon, W. (2001). Good work: When excellence and ethics meet. New York: Basic Books. Gelatt, H.B. (1989). Positive uncertainty: A new decision-making framework for counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 33, 252–256. Guichard, J. (2003). Career counseling for human development: An international perspective. The Career Development Quarterly, 51, 306–321. Hackney, H.L., & Cormier, L.S. (1996). The professional counselor: A proves guide to helping., (3rd ed.), Boston: Allyn and Bacon. Hall, D.T. (1996). The career is dead: Long live the career. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Hambley, L.A., & Magnusson, K. (2001). The receptivity of career practitioners toward career development resources on the internet. Canadian Journal of Counselling, 35, 288–297. Handy, C. (1994). The age of paradox. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. Hansen, S.L. (1996). Integrative life planning: Critical tasks for career development and changing life patterns. New York: John Wiley & Sons. Herr, E.L. (1999). Counseling in a dynamic society: Contexts and practices for the 21st century. Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association. Herr, E.L. (2003). The future of career counseling as an instrument of public policy. The Career Development Quarterly, 52, 8–17. Hiebert, B. (1994). A framework for quality control, accountability and evaluation: Being clear about the legitimate outcomes of career counselling. Canadian Journal of Counselling, 28, 334– 345. Homer-Dixon, T. (2000). The ingenuity gap. Toronto: Vintage Canada. Johnson, B. (2002). The intentional mentor: Strategies and guidelines for the practice of mentoring. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 33, 88–96. Magnusson, K. (2004). The efficacy of career development interventions: A synthesis of research. Unpublished paper. Ottawa: Human Resources and Skill Development Canada. McCormick, R., Amundson, N., & Poehnell, G. (2002). Guiding circles: An aboriginal guide to finding career paths. Saskatoon, SK: Aboriginal Human Resource Development Council of Canada. 14 NORMAN AMUNDSON Mitchell, K.E., Levin, A.S., & Krumboltz, J.D. (1999). Planned happenstance: Constructing unexpected career opportunities. Journal of Counseling and Development, 77, 115–124. Peavy, V. (2004). SocioDynamic counselling: A practical approach to meaning making. Chagrin Falls, OH: Taos Institute. Plant, P. (1999). Fringe focus: Informal economy and green career development. Journal of Employment Counseling, 36, 131–140. Pryor, R.G.L., & Bright, J.E.H. (2003). The chaos theory of careers. Australian Journal of Career Development, 12, 12–20. Pryor, R.G.L., & Bright, J.E.H. (2004, April). I had seen order and chaos, but had thought they were different. Presentation handout distributed at the Australian Association of Career Development Conference, Brisbane, Australia. Randolph, A.B. (1981). Managerial career coaching. Training and Development Journal, 35, 54–55. Sampson, J.P. (1999). Integrating internet-based distance guidance with services provided in career centers. The Career Development Quarterly, 47, 243–254. Sampson, J.P., Carr, D.L., Panke, J., Arkin, S., Minville, M., & Vernick, S.H. (2001). Design strategies for need-based Internet Web sites in counseling (Technical Report No. 28). Retrieved June 11, 2005 from Florida State University, Center for the Study of Technology in Counseling and Career Development (Web site: http://www.career.fsu.edu). Savickas, M. (2005). The theory and practice of career construction. In S.D. Brown, & R.W. Lent (Eds.), Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (pp. 42–70). Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons. Thrift, E., & Amundson, N. (2005). Hermeneutic-narrative approach to career counseling: An alternative to postmodernism. Perspectives in Education, 23, 9–20. United States General Accounting Office. (2003). Workforce investment act: One-Stop centers implemented strategies to strengthen services and partnerships, but more research and information sharing is needed. Retrieved June 11, 2005 from http://www.gao.gov/cgi-bin/getrpt?GAO-03725. Watts, T. (2003). Working connections: OECD observations. Ottawa: Canadian Career Development, Canada.