Differences between police and military

advertisement

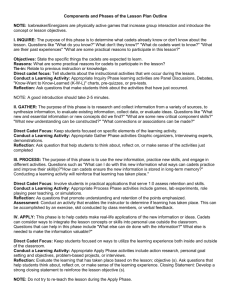

01-28-FOU 1-2011.fm Page 9 Wednesday, March 30, 2011 8:27 AM Identity in situation: Differences between police and military Kristian Firing, Ragnheidur Karlsdottir and Jon Christian Laberg This paper examines a case study of a military exercise conducted among cadets at four academies: the Norwegian Air Force, Navy, Army, and Police Academies (n = 128). When the cadets were presented with a case-study situation, we induced reflection as a mediating process for the actions they chose to take. While standing half-naked and blindfolded on a wharf, the cadets were given the option (offer) of either jumping or not jumping into the icy water, and were then also given the opportunity to reflect on the process before jumping or not jumping. The reflection process transformed the exercise from one of dealing with given options into dealing with a question of identity: Who am I in this situation? Exploration of the cadets’ reflection process disclosed different identities related to their academy affiliation. These differences were reflected in the cadets’ jumping rates, which ranged from 43% to 79% among the academies. One important implication of these findings is that identity in a given situation varies according to academy affiliation. Another important implication is how the reflection process transformed the situation from an offer of jumping into a question of identity, and thus may be a promising way of improving military education. Keywords: education, identity, situation, action, reflection Introduction We argue in this paper that self-awareness of identity is related to behavior in stress-related situations, and propose that reflection in situation is the process through which to explore such an identity. The significance of this work for officer cadets is that reflection develops knowledge with regard to the question of «Who am I?» in close relation to stress-related situations. Firing, K., Karlsdottir, R., & Laberg, J.C. (2011). Identity in a situation: Differences between police and military. Tidsskriftet FoU i praksis, 5(1), 9–28. 9 Kristian Firing Department of Education, NTNU kristian.firing@ lksk.mil.no Ragnheidur Karlsdottir Department of Education, NTNU ragnheidur.karlsdottir@ svt.ntnu.no Jon Christian Laberg Department of Psychosocial Science, UiB jon.laberg@psysp.uib.no 01-28-FOU 1-2011.fm Page 10 Wednesday, March 30, 2011 8:27 AM FoU i praksis nr. 1 2011 There has been very little research on identity in military situations. Identity has been addressed through large survey studies within military sociology (Battistelli, 1997; Franke, 2000; Franke & Heinecken, 2001) and military psychology (Bartone, Snook, Forsythe, Lewis, & Bullis, 2007) without tapping directly into military situations. Knowledge of identity in such situations is mostly provided post-action through investigation of real incidents (Snook, 2000; Zimbardo, 2007). Thus, the amount of research on identity in military situations is limited. However, Larsen’s (2001) study of military cadets firing their guns at people with what they thought was live ammunition is such an example. The research presented in this paper, which pays close attention to officer cadets’ reflections, is a unique contribution to such a line of research. Our point of departure was traditional, at least in a military context: half-naked, blindfolded officer cadets were led into a situation in which they were expected to perform an action. However, we interrupted their expected action by inducing a reflection process. We offered an action option and invited each cadet to participate in a reflective dialogue, disclosing personal arguments such as «mastering of stress and coping» and social arguments such as «I don’t want to be the only one not doing it.» The reflection process transformed the situation from a matter of action into a question of identity: «Who am I»? At an individual level, this process was unique. However, we asked whether there were aggregated differences based on academy affiliation. With this in mind, the aim of the study was to explore differences between the academies with respect to identity in a given situation. Sociocultural context During the Cold War, military doctrines regulated how and when military force should be used down to the final detail, and the armed forces had to follow fixed «standard operating procedures» (Flin, 1996, p. 35). Currently, however, officers must be prepared to switch between full-scale military actions, peacekeeping operations, and humanitarian relief missions (Forsvarsstaben, 2007). The parties involved can be a mix of civilians, paramilitary personnel, and/or military personnel, armed or otherwise. Thus, today’s officers need the capacity for divergent thinking in ambiguous situations (Segal, Moskos, & Williams, 2000). Such complexity presents certain pedagogical challenges. Military pedagogy is a process full of conflicts. On the one hand, soldiers are exposed to the process of socialization and need to take on a social identity (Arkin & Dobrofsky, 1978). On the other hand, they are supposed to undertake hermeneutic reflection and maintain their individual identity 10 01-28-FOU 1-2011.fm Page 11 Wednesday, March 30, 2011 8:27 AM Kristian Firing, Ragnheidur Karlsdottir and Jon Christian Laberg: Identity in situation: Differences between police and military (Toiskallio, 2008). The challenge to officer education is to cover this wide span in identity as it unfolds in the operative context. Military officer education is a full three-year program of studies that leads to a bachelor’s degree in military studies. The education is supported by an extensive mentoring system to enhance personal development. However, this mentoring, together with mentoring by the class commander, is also part of the evaluation process that culminates in the awarding of a grade in military conduct. This grade is important for further assignments within the service to such a degree that it can be assumed that it can promote or impede personal development (Steiro & Firing, 2009). The requirement to provide education for leaders that «combines practice and theory to develop reflective officers» (Luftkrigsskolen, 2005, p. 24) has led the Air Force Academy to base its education on the concept of learning from experience (Dewey, 1961; Skjevdal, Solheim, & Henriksen, 1995). The Academy has chosen to found its educational philosophy on three pillars: theory, reflection, and practical training (Firing & Laberg, 2010). Regarding theory within leadership, important themes are psychology, organizations, educational science, ethics, and theories of leadership. Reflection stands out as a key process. Based on the humanistic psychology of Rogers (1961), group guidance is the main process of reflection. Log writing has been developed into a method of reflection which both supports and is intertwined with group guidance (Firing, 2004). Practical training takes place within military exercises. During the Cold War the exercises were long endurance tests, where the drilling of fundamental military skills such as marching, shooting, donning gas protection, and practicing first aid was the primary focus. Exercises have followed a traditional design in which the reflection process has been accomplished post-action and has been undervalued. The traditional design of military exercises is shown in Figure 1. Figure 1: A model for traditional military exercises Within «Sociocultural Context,» people bring their «Identity» into a «Situation» in which «Action» is expected. Being part of such a sociocultural context may have impact on their identity. 11 01-28-FOU 1-2011.fm Page 12 Wednesday, March 30, 2011 8:27 AM FoU i praksis nr. 1 2011 Identity The essence and the organizing construct of the study presented here is the concept of «self». The self is organized into different identities, each related to different aspects of the social structure (Stets & Burke, 2003). Identity can be derived from several within-person sources, such as the individual, relational, family, and collective self (Sedikides & Gaertner, 2001). Self is closely connected to identity: while the self is the inner core, identity is what relates to the outside. Within authentic leadership, self-awareness is a process in which a person reflects on his or her identity, and in that way develops self-regulation where his or her behavior is made more autonomous (Gardner, Avolio, Luthans, May, & Walumbwa, 2005). Against the backdrop of authentic leadership, we propose the following three levels of identity as the basis of our study: personal, relational, and collective identity (Brewer & Gardner, 1996). Personal self focuses on the unique characteristics, including attributes, which specify how one differs from others, an approach that is basic in Western psychology (Brewer & Gardner, 1996). Working from this premise, Higgins developed the self-discrepancy theory, a systematic framework for revealing interrelations between three self-states: (1) the actual self, (2) the ideal self, and (3) the ought self (Higgins, 1987). Bearing this in mind, Higgins described two major types of discrepancy: the first type is between actual self and ideal self as associated with appraising a person’s hopes, wishes, or aspirations, and the second type is between the actual self and ought self, which is associated with appraising someone’s duties, obligations, or responsibilities. The theory of relational self holds that the self-concept is derived from connections and role relationships with significant others (Brewer & Gardner, 1996). This corresponds closely with social comparison theory as described by Festinger: «to the extent that objective, or non-social means are not available, people evaluate their options and abilities by comparison respectively with the options and abilities of others» (Festinger, 1954, p. 118). Moreover, the process of social comparison takes place between discrete individuals. Comparison with typical group members and aggregated standards, such as norms, also falls within social comparison’s purview (Alicke, 2007). The collective self corresponds to the concept of social identity theory evolving as a process. Initially, people quickly categorize between «ingroups» and «out-groups». Moreover, the intra-group change is made possible by people adjusting themselves in the direction of the accentuation of a perceived prototype of an in-group member. Finally, on an individual level, people are essentially depersonalized in the direction of an in-group prototype rather than a unique individual (Turner & Reynolds, 2004). 12 01-28-FOU 1-2011.fm Page 13 Wednesday, March 30, 2011 8:27 AM Kristian Firing, Ragnheidur Karlsdottir and Jon Christian Laberg: Identity in situation: Differences between police and military Bearing in mind that the role of a military officer is practiced in a stressful context (Forsvarsstaben, 2007), our point of departure is that identity is malleable to contextual variations (Sedikides & Gaertner, 2001). Using the three levels of identity, we will explore identity as a process of participation or non-participation (Wenger, 1998) in a situation where cadets face a matter of action. Situation Military operations place combatants in extreme situations where they may face the threat of losing their life or the responsibility for killing another human being. Military exercises cannot mirror such extreme reality; they are only a game to be played. However, what the player may not be aware of is that the game has its own seriousness as it is a process that takes place «in between» (Gadamer, 1989, p. 109). The game’s back-and-forth movement taps into the playful nature of the contest. Bearing this in mind, all playing is about being played. «Play fulfills its purpose only if the player loses himself in play» (Gadamer, p. 103). It is in this process of playing that the player can discover himself. Vygotsky adds to this when stating that meaning becomes the important process through which play is connected to pleasure but also to rules for renouncing impulsive action. The paradox is dealt with through the process of self-control in which rules are given privilege (Vygotsky, 1978). In our case, we intended to explore this process within a military exercise. Given that military exercises mirror modern operations, one can imagine that physical stress would be present in such situations. Such stress may move the players into the traditional stress and coping mode (Lazarus, 1999). Moreover, we argue that ambiguity and uncertainty should be facilitated (Bartone, 2008), encompassing social uncertainty (Hogg, 2007, p. 77). Finally, the situation should utilize various possible behavioral responses, forcing the players to take a course of action and reveal themselves to the other players. Action Initially, action may be thought of as a physical act; one performs a drill and follows a procedure. However, it is more than that. Following a sociocultural approach, action is the entry into an analysis of the mind: «Human beings are viewed as coming into contact with, and creating, their surroundings as well as themselves through the actions in which they engage» (Wertsch, 1991, p. 8). Moreover, the concept of «mediated action» points to the fact that «human action typically employs meditational means such as tools and language, and that these meditational means shape the action 13 01-28-FOU 1-2011.fm Page 14 Wednesday, March 30, 2011 8:27 AM FoU i praksis nr. 1 2011 in essential ways» (Wertsch, p. 12). Finally, action can be seen as a social act—an action performed in interaction with «the other» (Mead, 1934). Such a wide view of action is also visible in the definition of social psychology as «the thought, feeling, and behavior of individuals as shaped by the actual, imagined, or implied presence of others» (Allport, 1935, p. 3). Exploring such an extended view of action requires that the reflection process is in the foreground. The study Reflection is a key process in the current study.. Mead’s point of departure is that reflection makes possible positive control by the individual «with reference to the various social and physical situations in which it becomes involved and to which it reacts» (Mead, 1934, p. 91). Vygotsky elaborates on the reflection process further by emphasizing humans’ language as a major mediating tool in their thinking: «thought is not merely expressed in words; it comes into existence through them» (Vygotsky, 1986, p. 218). Such a use of a mediating tool cannot be understood in isolation, but has repercussions for the person using this tool: it mediates action or thinking (Vygotsky, 1978). Schön’s concept of «reflection in action» (Schön, 1983) indicates a close relation to a given situation and also that reflection might take place subconsciously as part of professional work. The concept of «reflection on action» indicates a more conscious reflection process in which language is used to make a distinction. Facing a new situation, the practitioner can acquire language to «make sense of an uncertain situation that initially makes no sense» (Schön, p. 40). Given that military personnel operate under conditions of great uncertainty, reflection is a key process in constructing experiences from which to learn (Dewey, 1961). The backdrop to our study was the traditional design of the exercise known as the «the water jump,» which was developed in police training and later adopted by military academies in Norway (Røkke, 2009). The study focused on merging the traditional design of military exercises with a reflection process, as shown in Figure 2. 14 01-28-FOU 1-2011.fm Page 15 Wednesday, March 30, 2011 8:27 AM Kristian Firing, Ragnheidur Karlsdottir and Jon Christian Laberg: Identity in situation: Differences between police and military Figure 2: A model of the water jump as a military exercise Figure 2 shows how the traditional design of military exercises (see Figure 1) is mirrored by the bar labeled «Sociocultural Context» and the three underlying boxes: «Identity,» «Situation,» and «Action». From there, the reflection process is illustrated by the triad «Situation,» «Action,» and «Reflection». The offer of jumping and the reflection process breaks the stimuli-response relation, making the action the background and the reflection dialogue the foreground. Given the above-described design of military exercises, the matter of identity in a given situation was explored based on «reflection in situation» and subsequent action. As our study involved people from different academies, the research question was: How can we understand differences between police and military academies regarding identity in a given situation? Methods The case study research approach was used. Creswell’s definition of case studies emphasizes exploration of a case through detailed in-depth data collection involving multiple sources of information (Creswell, 1998). The details of this process are outlined below. Participants The study participants came from the available population of first-year students at the Norwegian Air Force (n = 29), Navy (n = 37), Army (n = 42), and Police Academies (n = 20), in total 128 participants. The sample included 13 females and 115 males, of which 90% were between the ages of 21 and 30 years. The participants were attending studies as part of a three-year bachelor’s degree course. Participation in the research project was based on informed consent. All participants were thoroughly debriefed to ensure that the exercise was a 15 01-28-FOU 1-2011.fm Page 16 Wednesday, March 30, 2011 8:27 AM FoU i praksis nr. 1 2011 learning experience for them and to ensure that their integrity was preserved. Ethical approval of the study was granted by the Regional Ethics Committee of Mid-Norway in 2007. Procedure The military exercise took place during March and April in 2007. The water jump was part of the training programs at all four academies, and lasted between one and two days together with other similar exercises. The water jump started out as a regular exercise, with the cadets operating in their regular teams from a military field vehicle. At a checkpoint, they were met by a staff member from their academy, ordered to step out of the car and strip down to their underwear. A hood was then pulled over their heads to cover their eyes and they got back into the car; the cadets had no visibility outside the vehicle. After a five-minute drive to disorientate the cadets as to their position, the car stopped approximately 30 meters from a wharf. One by one, the cadets were taken out of the car, led over the icy ground, dressed in a life-jacket, given a safety line, and placed on the wharf. They were addressed as follows: «[…] you are now standing on a wharf and you are being given the option of jumping into the sea.» The dialogue evolved from that starting point. Initially, the cadets’ questions about the physical environment were answered briefly through utterances such as «three meters to the water» and «safety is well taken care of». Moreover, the basis for the decision was explored by the staff member, asking open questions such as «What is your reason for your decision?» and «Could there be further reasons?» Finally, the decision was executed by the cadets, either by jumping into the icy water or stepping back, taking off the hood, and being given their clothes. In both cases, the exercise participants were thoroughly debriefed to ensure that their integrity was preserved and to ensure that the water jump was a learning experience. Data collection In all cases the dialogue with the officers took place on the wharf. Interpretive listening and follow-up questioning were used to provide each cadet with the opportunity to reflect over the reasons behind the decision he or she had made. Openness and honesty were essential to make the cadets reveal his/her experience of the situation. Hence, the dialogues functioned as short field interviews, capturing the cadets’ thoughts and emotions in the process of making their decision about action in the situation that had been presented to them. All of the officer cadets were observed during the process on the wharf, and their behavioral response regarding whether or not to jump into the icy water was registered. 16 01-28-FOU 1-2011.fm Page 17 Wednesday, March 30, 2011 8:27 AM Kristian Firing, Ragnheidur Karlsdottir and Jon Christian Laberg: Identity in situation: Differences between police and military Data analysis Firstly, the dialogues from the wharf were audio-taped, transcribed, and analyzed to develop structures and categories for the cadets’ experience. This was based on the finding that the officer cadets commonly started off with a personal explanation for their decision, and that later most of them developed their explanation on a social level. Thus, personal level and social level became preliminary categories. Axial coding was used to interpret the material in close relation to theory on a personal and social level. Through the constant comparative method (Corbin & Strauss, 2008) these categories were then analyzed in more detail. Thus, the personal level was interpreted in connection with self-identity theory (Higgins, 2001). Moreover, the social level was developed into two sub-categories: the relational level (Festinger, 1954) and the collective level (Hogg, 2004). To summarize, the coding led to the following three categories: personal, relational, and collective identity. Secondly, observations of the cadets’ behavioral responses were analyzed using chi-square analyses. In particular each cadet’s decision, i.e., whether to jump or not, was analyzed in relation to the cadet’s academy affiliation. Results Even though there was an extreme and exotic context on the wharf, the reflection dialogue was the key process in our study. The identity of the cadets was disclosed through different lines of reflection and action, as shown in Table 1. Table 1: Identity in situation Reflection Action Navy Air Force/Police Army Personal No-jump Relational Jump Collective Jump Note: The Air Force and the Police are combined in one column due to similarities; a finding that will be further explored during the upcoming results. Reflection As shown in Table 1, the cadets’ reflections over the choice offered during the military exercise varied according to the four academies. While the navy cadets gave personal reasons to justify not jumping, the cadets from 17 01-28-FOU 1-2011.fm Page 18 Wednesday, March 30, 2011 8:27 AM FoU i praksis nr. 1 2011 the three other academies proposed social reasons for jumping, for example not wanting to be seen as «chicken». The three categories are outlined as follows. Navy: Personal. The main approach among the navy cadets was connected to meaningful adaptability (Benton, 2005) to the ambiguous situation. Typical of the reflections made in the dialogues on the wharf are the following: 1 Testing how I react when I get a little shock in cold water, maybe check it in connection with a shipwreck. (Navy, p. 12) 2 If there were people in the sea who needed to be rescued, then there could be a reason to jump into the water. Beyond that, I don’t see any reason to jump into the sea of my own free will. (Navy, p. 29) In the first quotation we can see how the cadet wanted to test how he would react if he were to «get a little shock in cold water». Thus, jumping into the icy water would presumably give the cadet first-hand experience in dealing with extreme conditions. The relevance is «in connection with a shipwreck,» which is within the operative range of being a naval officer. However, the cadet still puts himself in the center of the adaptation process (Benton, 2005). From part of the second quotation, «if there were people in the sea who needed to be rescued,» we can see how the cadet adapted to the situation by using an operative appraisal. Such adaptation was probably influenced by the Navy Academy’s focus on Boyd’s decision cycle (Boyd, 1995). The observe-orient-decide-act process encourages the cadets to employ operative reasoning. As no operative context or mission is given, the cadets do not see any reason to jump into the ocean of their «own free will». The latter mirrors a common tendency at the Naval Academy; the situation was adapted to on a personal and independent basis. Personal adaptation makes sense in light of self-discrepancy theory (Higgins, 1987). The underpinning could be the three different self-states: (1) the actual self, (2) the ideal self, and (3) the ought self. The choice, or offer, on the wharf addressed the cadets’ actual self—what would be sound adaptation for them in this situation. To some extent the offer also triggered the ideal self, a need to test or check oneself by jumping into the icy water. However, the offer did not trigger the ought self, expectations from oneself or others about jumping. Thus, our interpretation was that the navy cadets did not experience major self-discrepancies. They maintained their actual self and thus responded to their own lack of a need to jump into the icy water. Air Force/Police: Relational. The main approach among both air force and police cadets was connected to relational aspects of jumping versus not jumping. Typical of the reflections were the following: 18 01-28-FOU 1-2011.fm Page 19 Wednesday, March 30, 2011 8:27 AM Kristian Firing, Ragnheidur Karlsdottir and Jon Christian Laberg: Identity in situation: Differences between police and military 1 It’s a little embarrassing to be the only one not jumping (Police, p. 126). It might just be that I don’t want to be a non-jumper then. I can feel that it will be annoying if I’m the only one not jumping (Air Force, p. 39). 2 I don’t want to chicken out. That’s a major part of it, of course (Police, p. 128). I don’t want to be the one who hasn’t done it, because then you lose face. You probably understand what I mean by that (Air Force, p. 65). 3 If you have chosen a profession which demands that you eventually have to jump, then it may have been okay to have done it during an exercise beforehand (Police, p. 128). In the first set of quotations, the cadets mentally moved the water jump beyond the physical environment. They said that it would be «embarrassing» or «annoying» to be «the only one not jumping,» thus moving the water jump into a process of officers’ identity. These utterances reflect a relational identity: the cadet is exposed to a social comparison process in relation to an imagined presence of the other cadets (Festinger, 1954). People evaluate their performance in relation to the attainments of others, for instance to classmates in a similar situation (Bandura, 1991). Moreover, the utterances that expressed «I don’t want to be a non-jumper» addressed the relational identity as a matter of participation and non-participation (Wenger, 1998)—the former associated with the physical pain of the cold water, the latter with relational pain of being rejected from the group, being the «odd one out» (Brown, 2000, p. 135). The second set of quotations, «I don’t want to chicken out» brings the social comparison process beyond discrete individuals to aggregated standards, such as social norms (Alicke, 2007). In the military, values such as discipline, obedience, and courage appear in the culture and are internalized through the process of enculturation (Benton, 2005). In this context, not wanting to «chicken out» seems to reflect the social norm of courage. Thus, courage is associated with coping with the physical environment, in this case jumping into icy water. The consequence was that the cadets did not want to be the ones not jumping because «then you lose face». In the case of the single quotation above, the cadet referred to a «profession» that may demand activities such as jumping, and hence it may have been okay to «have done it» beforehand. Thus, through these utterances the cadet addressed another aggregate standard (Alicke, 2007). However, while obtaining first-hand experience of stress and coping was a common reason given by the cadets, such willingness may be difficult to separate from perceived social expectations and the potential social sanctions of not jumping. In other words, the police cadet’s willingness to jump based on his future «profession» as a decisive argument for jumping may have hidden the relational fear associated with not jumping. 19 01-28-FOU 1-2011.fm Page 20 Wednesday, March 30, 2011 8:27 AM FoU i praksis nr. 1 2011 Army: Collective. The main approach among the army cadets was connected to social aspects of not jumping and perceived consequences in relation to the academy teaching staff. Typical reflections were as follows: 1 I don’t want to chicken out either, because doing it doesn’t really worry me, but I would look at it as a major personal setback if I didn’t do it. (Army, p. 92) 2 I feel there’s an expectation that you should do it. Like a kind of group conformity, I don’t want to be the only one not jumping. (Army, p. 81) 3 I don’t have any immediate wish to jump into icy water, but if that’s something I have to do to attend the school here, then why not? (Army, p. 75) 4 I reckon that this is something the instructors and the academy staff have said will make me more of a man, so I probably have to do it. (Army, p. 84) The first utterance, «I don’t want to chicken out either,» taps into the relational self and the process of social comparison (Festinger, 1954). In the process of uncertainty, the cadet compared himself to an aggregated norm (Alicke, 2007). Moreover, we see the imaginary presence of the norm in the utterance «there’s an expectation that you should do it». Such expectations would truly influence the cadet’s own self-efficacy or at least his outcome efficacy (Bandura, 1997). All in all, this became a matter of «group conformity» (Brown, 2000), and the result was that he did not want to be «the only one not jumping». The utterance, «if that [jumping] is something I have to do to attend the school here», illustrates the army cadets’ social identity. Viewed from the position of a male army cadet, exercises such as the water jump will make him «more of a man». Such a social identity is best described through a process. Initially, being an army cadet and a man has an inter-group function. One discriminates against being a «random» student or being a woman by accentuating the differences in these categories. Moreover, the intra-group climate is accentuated in the direction of a perceived prototype of the ingroup member (Hogg, 2004). Finally, being a man, he «probably [has] to do it». He speaks from a collective identity; he is depersonalized. Looking back at the various categories, in the following we will follow the participants’ progress from the dialogue to their actual behavioral response on the wharf. Action In the ambiguous situation in the military exercise, the offer given was a point of departure for a reflective dialogue. However, the situation also demanded an action: the cadets either had to jump or not jump. The pro- 20 01-28-FOU 1-2011.fm Page 21 Wednesday, March 30, 2011 8:27 AM Kristian Firing, Ragnheidur Karlsdottir and Jon Christian Laberg: Identity in situation: Differences between police and military portion of those who jumped according to their academy affiliation is shown in Figure 3. Figure 3: Jumping rates by Academy affiliation (%) As illustrated, the jumping rate varied within the range 43.2% to 78.6%. Table 2: Academy affiliation and decision to jump or not: cross-tabulation No Jump Academy Navy Jump Total Count/Exp Count 21/12.7 16/24.3 37 Std. Residual 1.7 2.3 Air For- Count/Exp Count 9/10 ce Std. Residual Police Army Total .3 20/19 .2 Count/Exp Count 5/6.9 15/13.1 Std. Residual .5 .7 Count/Exp Count 9/14.4 33/27.6 Std. Residual 1.0 1.4 Count/Exp Count 44/44 29 84/84 20 42 128 Note: Pearson’s chi-square, c2 (3, N = 128) = 12.26, p <.007. No cells have an expected count less than 5. As can be seen in Table 2, the different proportions of jumping sorted by academy affiliation are statistically significant (chi-square (3, N = 128) = 12.26; p =.007). A closer look at the results of the chi-square analyses shows that only the cell Navy ‘No Jump’ contributes significantly (Std Residual = 2.3) to the chi-square result. However, the cell Army ‘No Jump’ has a Standardized Residual of 1.4. Even though it is not a significant contribution, it may reveal a tendency for army cadets to not prefer the ‘No jump’ option. The question is how these differences can be understood. 21 01-28-FOU 1-2011.fm Page 22 Wednesday, March 30, 2011 8:27 AM FoU i praksis nr. 1 2011 Discussion Our study explored differences between military academies regarding identity in a given situation, and the following discussion evolves in two directions: (1) «what» was found, i.e., the different identities in situation, and (2) «how» these empirical findings were revealed, i.e., the reflection as a key process. Identity in situation Our point of departure for identity was that it is contextually determined (Sedikides & Gaertner, 2001), and in this regard we applied different levels of identity: personal, relational and collective (Brewer & Gardner, 1996). What we found was the emergence of a preferred identity in the situation that the cadets were presented with. At the individual level, the negotiation of doing and not-doing was a genuine process. However, when looking at identity made salient at an aggregated level, differences were revealed. It may be questioned whether such differences could be understood from a physical perspective. Regarding the physical environment, the icy water, height, and hood functioned as important elements in activating the cadets’ thinking and emotions in connection with the offer to take action. On the one hand, such elements are common during stress and coping exercises in all the academies. On the other hand, the element of icy water may have especially influenced the navy cadets by triggering an operative reasoning along with Boyd’s decision cycle (Boyd, 1995). In such cases, the lack of any operative reason may have led to the tendency to not jump. However, looking beyond the physical environment, one major distinction is apparent. The navy cadets showed a sense of personal identity when they paid less attention to what they thought the other cadets would do. Having no operative reason, the typical cadet did not see any reason to jump into the ocean of his or her «own free will». The question is whether this was an act of independent thinking, or whether it simply was expected operative reasoning, along with Boyd’s decision cycle (Boyd, 1995), within the naval profession. Social identities were observed among the cadets from the Air Force, Police and Army Academies. Relational identity was reflected in a fear of being «the only one not jumping». The latter utterance mirrors the social comparison theory process (Festinger, 1954), in which the cadets evaluated the options by comparison to the other cadets. Assuming that the others would have a tendency to jump, the cadets may have been left with a fear of being «the only one» associated with negative social consequences, such as being rejected by the group and being the «odd one out» (Brown, 2000, p. 135). A collective identity was revealed among cadets in their reflections on their status as cadets and, in the case of male cadets, being «a man». Within 22 01-28-FOU 1-2011.fm Page 23 Wednesday, March 30, 2011 8:27 AM Kristian Firing, Ragnheidur Karlsdottir and Jon Christian Laberg: Identity in situation: Differences between police and military social identity theory (Turner & Reynolds, 2004), this may point to a categorization between in-groups and out-groups, where a perceived prototype of the in-group member is a «man» who chooses to jump. From this depersonalized position of conforming to the perceived prototype, the result was to jump into the icy water. The different levels of identity, personal, relational, and collective, are not an «either/or» situation. The levels of identity most certainly coexist (Brewer & Gardner, 1996). However, what we have seen is the preferred identity as it played out in the studied situation. The process of disclosing this identity was helped by the process of reflection. Reflection as a key process Reflection in situation was the key process for revealing the empirical findings in our study. Bearing this in mind, we now question whether reflection in situation could make a positive contribution to military education. Viewed in these terms, the reflection process can be envisioned as taking place in three different ways. The first form of reflection is an activity-based perspective where one focuses on the activity itself and overcome obstacles according to one’s abilities (Dewey, 1980). Traditionally, activity-based training has had a central role in officer training based on behavioristic pedagogy (Skinner, 1953). The immediate interpretation of the water jump exercise is probably focused on the physical environment: coldness, height, safety, and so forth. Utterances such as «own free will» confirm such a limited perspective of reflection. The second form of reflection is a synthetic perspective: thinking about the activity without carrying it out. This perspective touches on the same issues, and perhaps also addresses some social issues. However, the missing part in the analogy is the construction of knowledge. Hence, the quality in such a reflection remains incomplete because the mind cannot construct the connection between the conducted activity and the felt consequence (Dewey, 1980). The third, and final, form of reflection occurs between mechanical doing and pure thinking. Here, the thinking is focused on the activity and the consequences in order to construct the relationship between the two and fulfill the experience (Dewey, 1980). Within the water jump context, the following questions were considered: (1) What would the cadets do? (2) What were the perceived consequences? (3) What was the connection between jumping as opposed to not jumping and the perceived consequences? Viewed in terms of this experience-based reflection, different identities, but also different educational practices may be revealed. 23 01-28-FOU 1-2011.fm Page 24 Wednesday, March 30, 2011 8:27 AM FoU i praksis nr. 1 2011 The individual orientation was connected to the harsh physical environment and the lack of an intended mission. Even the cadets who wanted to jump provided us with individual reasons, namely wanting to test their ability to cope with icy water. These reflections mirrored an adaptation towards the environment, as described by Piaget’s process of assimilation and accommodation (Piaget, 1977). Following this perspective, the cadets did not reflect on peer pressure or social expectations in the situation they were presented with. The social orientations appeared in the range from behaviorism to sociocultural perspective. On the one hand, the build-up to the water jump, ordering officer cadets to undress, wear a hood, and step on to the wharf, may reflect a behaviorist perspective (Skinner, 1953). Following this line further, the solution was to jump into the icy water. On the other hand, the water jump could be seen from a sociocultural perspective (Vygotsky, 1978). The exercises would give opportunities to learn about one’s stress reactions and coping ability with challenging operative situations. However, cultural force may have encouraged the cadets to conform to peer pressure and organizational expectations to act courageously. The expectation to show courage by jumping may thus be a bridge back to a behavioral perspective whereby cadets perform to gain a reward or avoid punishment (Skinner, 1953). Thus, in an applied context, there may be little difference between a behavioral perspective where we find more explicit guidelines for reward and punishment and sociocultural perspectives where the cultural forces implicitly give one limited room for choice. Implications In accordance with the line of authentic leadership (Gardner et al., 2005), exploration of identity provided the cadets with self-awareness connected to the identity made salient in the context. The revealed differences have implications in different directions. Self-awareness of one’s tendency to take on a collective identity can imply a high level of conformity (Brown, 2000). This can be used as an advantage in some operations, although it may well also be the first step on the way to selfregulating in the direction of a personal identity, protecting cadets from exaggerated macho action in cases where the consequences of such behavior might be devastating. The paradox is that this could just as easily be turned around. Self-awareness of personal identity, implying diversity and anti-conformist behavior, could be a point of departure for self-regulation towards a collective identity in cases where this would be required. Making military personnel aware of the potential of self-awareness and self-regulation could be a promising way of bridging soldiers’ social identity and individual character, and could thus enhance performance. 24 01-28-FOU 1-2011.fm Page 25 Wednesday, March 30, 2011 8:27 AM Kristian Firing, Ragnheidur Karlsdottir and Jon Christian Laberg: Identity in situation: Differences between police and military Limitations The study presented in this paper was based on officer cadets in the Police and the Armed Forces who were studying for a bachelor’s degree. The findings might not be readily generalized to the target population of all officer cadets, or other civilian students. Moreover, the context of the water jump exercise could be difficult to apply to other military or civilian situations. However, if one is willing to look at the situation as providing an opportunity for reflective dialogue which taps into the range of identity, from personal identity to collective identity, generalization may be possible. Conclusion The findings in our study were derived from a special research design: stopping an expected action and opening for a reflection process that transformed a given situation from a matter of action into a matter of identity. Bearing in mind our process of constructing knowledge of identity in situation, we argue that our research design might be a promising way of improving military education. Having explored identity as it played out in a specific situation, we found that it was a unique process on the individual level, but there were differences on the group level. However, we do not argue that a collective identity is bad and that a personal approach is good, or that one leads to problems and the other to solutions. Rather, we propose that an enhanced level of selfawareness of identity, on both an individual level and a group level, could be a vehicle into self-regulation for authentic leaders in (at times) extreme situations. Literature Alicke, M. D. (2007). In defence of social comparison. Revue Internationale de Psychologie Social, 20(1), 11–30. Allport, G. W. (1935). The historical background of social psychology. In G. Lindzey & E. Aronson (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (vol. 1, pp. 1– 46). Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. Arkin, W., & Dobrofsky, L. R. (1978). Military socialization and masculinity. Journal of Social Issues, 34(1), 151–168. Bandura, A. (1991). Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 248–287. Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy. The exercise of control. New York: Freeman. Bartone, P. T. (2008). Lessons of Abu Ghraib: Understanding and preventing prisoner abuse in military operations. Defense Horizons, 8(64), 1–8. 25 01-28-FOU 1-2011.fm Page 26 Wednesday, March 30, 2011 8:27 AM FoU i praksis nr. 1 2011 Bartone, P. T., Snook, S. A., Forsythe, G. B., Lewis, P., & Bullis, R. C. (2007). Psychosocial development and leader performance of military officer cadets. Leadership Quarterly, 18(5), 490–504. Battistelli, F. (1997). Peacekeeping and the postmodern soldier. Armed Forces & Society, 23(3), 467–484. Benton, J. C. (2005). Air Force officer’s guide (34th ed.). Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. Boyd, J. R. (1995). The essence of winning and losing. A five slide set by Boyd, 28 June 1995. Brewer, M. B., & Gardner, W. (1996). Who is this «we»? Levels of collective identity and self representations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 17(1), 83– 93. Brown, R. (2000). Group processes. Dynamics within and between groups. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (3rd ed.). Los Angeles: Sage. Creswell, J. W. (1998). Qualitative inquiry and research design. Choosing among five traditions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Dewey, J. (1961). Democracy and education. An introduction to the philosophy of education. New York: The Macmillan Company. Dewey, J. (1980). Art as experience. New York: Berkley Publishing Group. Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7(2), 117–140. Firing, K. (2004). «Prøver å forstå litt mer i stedet for å være så sinna». En kasusstudie om skriving som refleksjonsform ved Luftkrigsskolen. [«Trying to understand a little more instead of being so angry». A case study of writing as a form of reflection at the Air Force Academy]. Trondheim: Tapir Akademisk Forlag. Firing, K., & Laberg, J. C. (2010). Training for the unexpected: How reflection transforms hard action into learning experiences. In P. T. Bartone, B. H. Johnsen, J. Eid, J. Violanti, & J. C. Laberg (Eds.), Enhancing human performance in security operations: International and law enforcement perspectives (pp. 229– 244). Washington, DC: Charles C. Thomas. Flin, R. (1996). Sitting in the hot seat. Leaders and teams for critical incident management. Chichester: Wiley. Forsvarsstaben. (2007). Forsvarets fellesoperative doktrine [The Norwegian Armed Joint Operational Doctrine]. Oslo: Author. Franke, V. C. (2000). Duty, honor, country: The social identity of West Point cadets. Armed Forces & Society, 26(2), 175–202. Franke, V. C., & Heinecken, L. (2001). Adjusting to peace: Military values in a cross-national comparison. Armed Forces & Society, 27(4), 567–595. Gadamer, H. G. (1989). Truth and method (2nd rev. ed.). London: Sheed & Ward. Gardner, W. L., Avolio, B. J., Luthans, F., May, D. R., & Walumbwa, F. O. (2005). Can you see the real me? A self-based model of authentic leader and follower development. Leadership Quarterly, 16(3), 434–372. Higgins, E. T. (1987). Self-discrepancy: A theory relating self and affect. Psychological Review, 94(3), 319–340. Higgins, E. T. (2001). Promotion and prevention experiences: Relating emotions to non-emotional motivational states. In J. P. Forgas (Ed.), Handbook of affect and social cognition (pp. 186–212). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates. 26 01-28-FOU 1-2011.fm Page 27 Wednesday, March 30, 2011 8:27 AM Kristian Firing, Ragnheidur Karlsdottir and Jon Christian Laberg: Identity in situation: Differences between police and military Hogg, M. A. (2004). Social categorization, depersonalization, and group behavior. In M. B. Brewer & M. Hewstone (Eds.), Self and social identity (pp. 203–231). Malden, MA: Blackwell. Hogg, M. A. (2007). Uncertainty-identity theory. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (vol. 39, pp. 69–126). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. Larsen, R. P. (2001). Decision making by military students under severe stress. Military Psychology, 13(2), 89–98. Lazarus, R. S. (1999). Stress and emotion. A new synthesis. New York: Springer. Luftkrigsskolen. (2005). Studiehåndbok for Luftkrigsskolen kull 56. [Studies information guide for the Air Force Academy class 56]. Trondheim: Author. Mead, G. H. (1934). Mind, self, and society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Piaget, J. (1977). The development of thought. Equilibration of cognitive structures. New York: Viking Press. Rogers, C. R. (1961). On becoming a person: A therapist’s view of psychotherapy. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. Røkke, T. (2009). The origin of the exercise «The Water Jump». Interview, 28 October 2009 by Kristian Firing, Trondheim. Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner. How professionals think in action. New York: Basic Books. Sedikides, C., & Gaertner, L. (2001). The social self. The quest for identity and the motivational primacy of the individual self. In J. P. Forgas, K. Williams, & L. Wheeler (Eds.), The social mind. Cognitive and motivational aspects of interpersonal behavior (pp. 115–138). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Segal, D. R., Moskos, C. C., & Williams, J. A. (2000). The postmodern military. Armed forces after the cold war. New York: Oxford University Press. Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and human behavior. New York: Macmillan. Skjevdal, J., Solheim, J. A., & Henriksen, R. E. (1995). Håndbok i lederskap for Luftforsvaret [Handbook of leadership for the Air Force]. Oslo: Luftforsvarsstaben. Snook, S. A. (2000). Friendly fire. The accidental shootdown of U.S. Black Hawks over Northern Iraq. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Steiro, T. J., & Firing, K. (2009). Coaching and mentoring in military training: An educational perspective. In R. Kvalsund & R. Karlsdóttir (Eds.), Mentoring og coaching i et læringsperspektiv [Mentoring and coaching in a learning perspective] (pp. 211–226). Trondheim: Tapir Akademisk Forlag. Stets, J. E., & Burke, P. J. (2003). A sociological approach to self and identity. In M. R. Leary & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), Handbook of self and identity (pp. 128–152). New York: Guilford Press. Toiskallio, J. (2008). Military pedagogy as a human science. In T. Kvernbekk, H. Simpson, & M. Peters (Eds.), Military pedagogies and why they matter (pp. 127– 144). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. Turner, J. C., & Reynolds, K. J. (2004). The social identity perspective in intergroup relations: Theories, themes, and controversies. In M. B. Brewer & M. Hewstone (Eds.), Self and social identity (pp. 259–277). Malden, MA: Blackwell. Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society. The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Vygotsky, L. S. (1986). Thought and language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice. Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 27 01-28-FOU 1-2011.fm Page 28 Wednesday, March 30, 2011 8:27 AM FoU i praksis nr. 1 2011 Wertsch, J. V. (1991). Voices of the mind. A sociocultural approach to mediated action. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Zimbardo, P. (2007). The Lucifer effect. Understanding how good people turn evil. New York: Random House. 28