Daniel Sharfstein, Vanderbilt University, Law School

advertisement

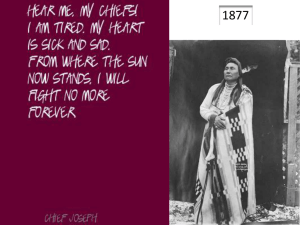

Bureaucracy in the Wilderness: Chief Joseph’s Advocacy for the Nez Perce Daniel J. Sharfstein The Wallowa Valley in far northeastern Oregon is an unlikely setting for a legal or intellectual history of bureaucracy in the United States. Just getting into the valley is a grueling physical ordeal. In the spring of 1872, when the first homesteaders ventured over from the Grande Ronde Valley, they found the mountains bounding the Wallowa country to the west to be so steep that they had to take their wagons apart, carry them up piece by piece, and then reassemble them for the ride down. As they rolled downhill, using felled tree trunks as anchors, the pioneers looked out onto paradise: thick forests, a criss-cross of streams and creeks, and gentle prairies swaying with bunchgrass.1 They were alone on the land—no law, no intellectuals, and no bureaucracy. That summer, as the homesteaders staked their claims, built crude shelters, and began stacking hay, a band of several hundred Nez Perce Indians emerged from their winter camp in the deep canyons that bounded the valley to the northeast. They had always spent the warm months in the Wallowa Valley, running their enormous herds of horses and cattle, catching and preparing several tons of salmon from the local streams, and hunting bear, elk, deer, pronghorn antelope, and big horn sheep in the forests. It was sacred country, where the father of the band’s two chiefs, Heinmot Tooyalakekt (Thunder Rising to Ever Loftier Heights) and Ollokut (Frog), was buried. As he lay dying in the summer of 1871, the old chief told his sons, “Always remember that your father never sold his country. . . . A few years more, and white men will be all around you. They have their eyes on this land. . . . This country holds your father’s body. Never sell the bones of your father and your mother.”2 1 See GRACE BARTLETT, THE WALLOWA COUNTRY, 1867-1877, at 20-21 (1984); The Innocents Abroad, THE MOUNTAIN SENTINEL (La Grande, Or.), Jy. 6, 1872, at 2. 2 An Indian’s View of Indian Affairs, 128 N. AM. REV. 412, 419 (1879). 1 Upon encountering white settlers in 1872, Heinmot Tooyalakekt informed them in the regional trade language, Chinook Jargon, that they were trespassing on his land. The homesteaders claimed that under an 1863 treaty with the Nez Perce, the Wallowa Valley had been ceded to the United States and opened to the public domain. Heinmot Tooyalakekt countered that his father had rejected the treaty. The Nez Perce, he said, were a grouping of autonomous bands, and the chief who had signed the treaty—a Presbyterian convert with the inauspicious name Lawyer, who lived a hundred miles away in Idaho Territory—did not represent the Wallowa band and had no authority to give away the valley. After several of these conversations, Heinmot Tooyalakekt traveled to the Grande Ronde Valley to attend a local Fourth of July celebration, where he was told he could find a congressman as well as a former federal Indian superintendent for Oregon. After a parade, potluck, and recitation of patriotic speeches, the chief, by this point known to the settlers as Joseph, made his case to the two dignitaries for why his band should keep their land.3 Over the next five years, until 1877, Chief Joseph tried to hold onto the Wallowa Valley. Crossing paths with a range of federal officials, civilian and military, he developed and perfected a number of arguments to claim ownership; he invoked treaty rights, core principles of property and contract law, and the constitutional values of liberty and equality. Almost immediately, though, Joseph realized that substantive legal arguments, no matter how compelling, were not enough. In order to alter federal Indian policy while thousands of miles away from the capital, Joseph had to figure out where American power was located and how it could be reached. The personal letters, newspaper accounts, and formal transcripts that memorialize Joseph’s encounters with federal bureaucrats have long been regarded as invaluable sources for 3 Interesting Wow-Wow, THE MOUNTAIN SENTINEL (La Grande, Or.), Jy. 6, 1872, at 3. 2 understanding the conquest of the American West and the final moments of traditional Native American sovereignty.4 But Joseph’s search for American power also reveals an underappreciated intellectual history, characterized by critical insights into how the post-Civil War administrative state functioned and what it required of its subjects. During the course of his advocacy, Joseph saw how American bureaucracy could be responsive to outside voices, yet its decisions were fluid and vulnerable to change. To be heard by the state when no action seemed final required a level of sustained activism that tested the chief and bureaucrats in novel ways in the years following Reconstruction. In just about every meeting with Chief Joseph from 1872 to 1877, government officials would listen to him respectfully and then give the same response, almost verbatim: that they had no authority to do anything that would stop the settlement of the Wallowa Valley. Everyone Joseph encountered either was too low in the bureaucracy, too impossibly far out in the field, or in a part of the government that lacked jurisdiction over the situation. It was strange to Joseph to see power so divided and decentralized that it seemed impossible to locate its source.5 Joseph secured promises from various functionaries that they would write letters to “higher authorities” in Washington, yet no one seemed sure what that would accomplish. Despite such daunting prospects, within a year of his first efforts, Joseph had secured an unprecedented action from President Grant: a June 1873 executive order taking an enormous section of the Wallowa Valley out of the public domain and reserving it as a seasonal hunting, fishing, and herding ground for “the roaming Nez Perce Indians.” The General Land Office 4 See, e.g., ELLIOTT WEST, THE LAST INDIAN WAR: THE NEZ PERCE STORY (2009); ALVIN M. JOSEPHY, JR., THE NEZ PERCE INDIANS AND THE OPENING OF THE NORTHWEST (1965). 5 In one 1876 meeting Joseph expressed frustration at the fragmented nature of power in the United States, which left seemingly no one responsible for crimes committed by white settlers against the Nez Perce. See H. CLAY WOOD, SUPPLEMENTARY TO THE REPORT ON THE TREATY STATUS OF YOUNG JOSEPH (1878) (“Joseph said that among the Indians the chiefs controlled the members of their bands . . . and he reasoned that those in authority over the whites had or should have, the same control over their men.”) 3 stopped registering homesteads, and the Interior Department began appraising existing settlements in order to buy them out. Joseph, it seemed, had found a path to power, from the Indian agents on reservations to regional supervisors in each state and territory to the Office of Indian Affairs in Washington to the Interior Secretary to the President. The chief’s success, however, was short-lived. Almost immediately, the bureaucratic process that secured his claim to the valley began to reverse itself. Despite reports that the Wallowa homesteaders were grateful to be relieved of the burden of living in such a harsh place, settlers in eastern Oregon enlisted their governor and congressional delegation to pressure the Interior Department and President to open the land up to settlement once again. They argued that the executive order undermined the Grant Administration’s “Peace Policy,” which forced Indians onto reservations and into lives as settled, Christian farmers, and that the order threatened to empower innumerable small bands to withdraw from their tribe’s treaties and hold out for better terms. Within a few months of the June order, the local Indian agent was again pressuring Joseph to abandon the valley for a reservation in Idaho Territory. The government stopped appraising the improvements on Wallowa homesteads and never allocated funds to compensate settlers. And in the late spring of 1875, President Grant issued a new executive order rescinding the 1873 action and restoring the valley to the public domain. Grant’s reversal in 1875 could easily have been the end of Joseph’s brief career as an advocate for his people. But as government policy switched from opening the Wallowa country to settlers to reserving it to Joseph’s band and back again, the chief had a keen insight into the administrative state that was emerging after the Civil War. As the first subjects of its full, unmediated power—freedpeople and Native Americans—experienced, the new federal state could cover vast territory and had tremendous ambitions to regulate how people lived and 4 worked and thought about their place in American society.6 What Joseph saw, however, was that even as the federal government was developing enormous capacity to enforce its policies, the apparatus that set those policies in the first place remained fluid and indeterminate. Its overlapping amalgam of competing authorities—civilian and military, legislative and executive, local, regional, and national; civilian and military—represented multiple paths to power that connected the remotest corners of United States to the capital. If the administrative state relied on unelected officials to govern, those officials were remarkably responsive to outside voices. 7 The government was so responsive, in fact—it could change direction so easily—that there seemed to be little reason to regard its decisions as final, even when they bore the trappings of finality of, say, an order signed by the President. It was a regime that begged for conflict, requiring parties to engage in unrelenting struggle over the meaning of law and the scope of their rights.8 Joseph quickly came to understand that he retained an active role in the state that was trying to “civilize” him.9 6 See, e.g., WILLIAM S. MCFEELY, YANKEE STEPFATHER: GENERAL O.O. HOWARD AND THE FREEDMEN (1968); STEPHEN J. ROCKWELL, INDIAN AFFAIRS AND THE ADMINISTRATIVE STATE IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY (2010). 7 This responsiveness was certainly the case in areas of government that were driven by facilitative payments, see NICHOLAS R. PARRILLO, AGAINST THE PROFIT MOTIVE: THE SALARY REVOLUTION IN AMERICAN GOVERNMENT, 1780-1940, at 162-72, but Joseph’s encounter with the state suggests that the bureaucracy’s flexibility and liberality were not entirely a function of money, although American Indian policymakers were consistently faced corruption charges. See ROCKWELL, supra note 6, at 250-51. 8 These struggles were not limited to the conquest and displacement of Native Americans in the West; arguably they also defined Reconstruction in the South. Such struggles over administrative policy seemed to require more formal and calculated engagement with legal and bureaucratic processes than, say, the “competing and conflicting socially constituted visions of legal order” embodied by the enduring customary practices of butchers who ran pigs in the streets of nineteenth-century New York. See Hendrik Hartog, Pigs and Positivism, 1985 WISC. L. REV. 899, 934 (1985). 9 When government officials in 1873 started urging Joseph to accept allotments on the reservation, he did not simply refuse. He asked the Nez Perce tribe’s Indian Agent to send him to Washington for an audience with President Grant. The agent initially thought Joseph’s request “was mere jest of his but two days later,” the agent wrote the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, “he . . . renewed his request that I be sure and write to the Great Chief, saying he wished very much to go to Washington and have a talk with him, in regards to their affairs.” John B. Monteith to E.P. Smith, Nov. 22, 1873, Lapwai Reservation Letterbooks, Nez Perce National Historical Park, Spalding, Idaho. 5 Starting in 1874, the Indian Agent began requesting that cavalry companies ride to the Wallowa Valley in order to keep the peace between settlers and the Nez Perce. Rather than view them as a hostile occupying force, Joseph treated the soldiers as part of another federal bureaucracy, a new path to the President, from cavalry officers to post commanders to the Department of the Columbia to the Division of the Pacific to General Sherman to the Secretary of War and up to the commander-in-chief. With the officers Joseph began pressing his case in much the same way he had in 1872 and 1873. Letters and reports from cavalry lieutenants found their way to the Department of the Columbia’s adjutant general, a trained lawyer who determined in a lengthy pamphlet published in January 1876 that under all applicable treaties and case law, Joseph’s band’s claim to the Wallowa Valley trumped that of the settlers.10 Even though the 1875 executive order purported to resolve the matter with finality, the adjutant’s pamphlet triggered a chain of events that led in October 1876 to the formation of a commission charged with negotiating with Joseph and ending the dispute peacefully. Three of the five commissioners were civilians from the east, and the other two were the Army commander of the Department of the Columbia and his adjutant.11 When Joseph faced them in November 1876, he was optimistic that they would reopen the Wallowa question. Instead, the commissioners informed Joseph at the outset that their primary task was to offer him a “favorable settlement” to abandon the valley and settle on the reservation. For three days the 10 H. CLAY WOOD, THE STATUS OF YOUNG JOSEPH AND HIS BAND OF NEZ-PERCE INDIANS UNDER THE TREATIES BETWEEN THE UNITED STATES AND THE NEZ-PERCE TRIBE OF INDIANS, AND THE INDIAN TITLE TO LAND (1876). 11 The commander of the Department of the Columbia, General Oliver Otis Howard, had rejoined the active duty military in 1874 after serving nearly a decade as head of the Freedmen’s Bureau, the first large federal social welfare bureaucracy. Traumatized and nearly bankrupted by the enemies of Reconstruction, Howard traced his downfall and his agency’s ruin to the fact that he had too often exercised his discretion in giving the most “sanguine” readings to statutes in order to help the freedpeople, rather than having “been more rigid & exacting & stuck to the literal rendering of the law.” See Letter from Oliver Otis Howard to Rowland Bailey Howard, Feb. 17, 1874, Letterbooks, Roll 7, O.O. Howard Papers, Bowdoin College. He was determined not to make the same mistake twice. 6 commissioners urged Joseph to take their deal. But he refused their terms, largely because he refused to believe that they were the final arbiters of the ownership of the valley. Warning Joseph that “he must not complain if evil happens to him,” the commissioners set in motion a plan to force the Indians out of the valley.12 The commission regarded the chief not as an active and constructive participant in the governing process, but rather as someone who was subverting it—a crucial determination for administrators in the field. By the following summer, the United States was at war with Joseph’s band. The Nez Perce War of 1877, which lasted several months as non-treaty bands fled 1500 miles through the northern Rockies in an attempt to join Sitting Bull in Canada, immortalized Joseph as a hero of civil and human rights, one of the few Indian chiefs remembered more for his words and ideas than for his battlefield prowess.13 Joseph’s expansive sense of liberty and equality made him a leading figure of dissent from the nation’s post-Reconstruction consensus. “We only ask an even chance to live as other men live,” he stated in a widely read article based on a speech he gave after the war. “Let me be a free man—free to travel, free to stop, free to work, free to trade where I choose, free to choose my own teachers, free to follow the religion of my fathers, free to think and talk and act for myself—and I will obey every law, or submit to the penalty.”14 The rhetoric is so poignant and powerful that it is easy to overlook that Joseph was not simply making a plea for what we might call citizenship. More specifically, he was trying to define citizenship in an administrative state and claim the right to speak to the state—to participate in the contentious struggles that a fluid and decentralized bureaucracy required—and to be heard. 12 EIGHTH ANNUAL REPORT OF THE BOARD OF INDIAN COMMISSIONERS FOR THE YEAR 1876, at 57-64. Although often hailed as a brilliant general—the “Red Napoleon”—Joseph was not a war chief and did not plan Nez Perce battle tactics. WEST, supra note 4, at 291. 14 An Indian’s View of Indian Affairs, supra note 2, at 433. 13 7

![Title of the Presentation Line 1 [36pt Calibri bold blue] Title of the](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005409852_1-2c69abc1cad256ea71f53622460b4508-300x300.png)

![[Enter name and address of recipient]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006894526_1-40cade4c2feeab730a294e789abd2107-300x300.png)