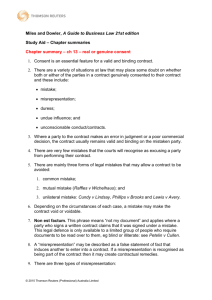

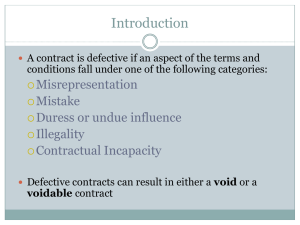

misrepresentation: the restatement's second mistake

advertisement