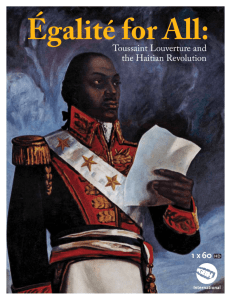

Impact of the Haitian Revolution on the Americas

advertisement

The following interview appeared in the PBS documentary “Africans in America.” In Part 3 (“Brotherly Love”) Douglas Egerton, a Professor of History at Le Moyne College, discussed the impact of the Haitian Revolution on American society. Modern Voices: Douglas Egerton on the Haitian Revolution, Toussaint L’Ouverture, and Thomas Jefferson [Adapted for Student Understanding] Question: What was the impact of the Haitian Revolution on Americans, black and white? How did Americans perceive Toussaint? What did Jefferson think about Haiti? Answer: All of the American newspapers covered the events in Saint Domingue (Haiti) in great detail. All Americans understood what was happening there. It wasn't that the revolution in Saint Domingue taught mainland slaves [slaves living in the U.S.] to be rebellious or to resist their bondage. They had always done so, typically as individuals who ran away attempting to escape to the frontier… [or]… as groups that established maroon societies [illegal slave communities established in wilderness areas]. But the revolutionaries in Saint Domingue, led by Toussaint L'Ouverture, were not trying to pull down the power of their masters, but join those masters on an equal footing in the Atlantic world. And the revolt in Haiti reminded American slaves, who were still enthusiastic about the promise of 1776, that not only could liberty be theirs if they were brave enough to try for it, but that equality with the master class might be theirs if they were brave enough to try. For black Americans, this was a terribly exciting moment, a moment of great inspiration. And for the southern planter class, it was a moment of enormous terror. The planter class was scared of L'Ouverture, and had no doubts that he knew exactly how to get what he wanted. His name, L'Ouverture, is a name that his soldiers applied to him. It meant this was a man who always found his opening. In the southern white mind, Toussaint was a terrifying but very competent figure. He was often depicted in southern newspapers as sort of a black Napoleon, somebody who could always find his opening, somebody who would always be successful in battle. There was no doubt in the white mind that they were dealing with a very fierce and very dangerous foe. Although it's quite clear that Toussaint was deeply inspired by events both in France and the United States, and some of his chief lieutenants had in fact been on the American mainland with the French army during the American Revolution, Jefferson was always the first to deny any sort of revolutionary heritage to people other than whites of European descent. Jefferson was terrified of what was happening in Saint Domingue. He referred to Toussaint's army as cannibals. His fear was that black Americans… would be inspired by what they saw taking place just off the shore of America. And he spent virtually his entire career trying to shut down any contact, and therefore any movement of information, between the American mainland and the Caribbean island. He called upon Congress to abolish trade between the United States and the independent country of Haiti. He argued that France still owned the island. In short, he denied that Haitian revolutionaries had the same right to independence and autonomy that he claimed for American patriots. And consequently, in 1805 and finally in 1806, trade was formally shut down between the United States and Haiti, which decimated the already fragile Haitian economy. And of course, Jefferson then argued that this was an example of what happens when Africans are allowed to govern themselves: economic devastation, caused in large part by his own economic policies. Source: Douglas Egerton. PBS Interview: The Haitian Revolution, Toussaint L’Ouverture, and Thomas Jefferson. Program: “Africans in America” (Part 3), 1998. Retrieved from: www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part3/3i3130.html