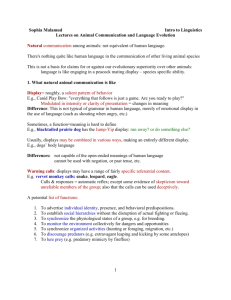

on the Evolutionary Roots of a Cultural Phenomenon

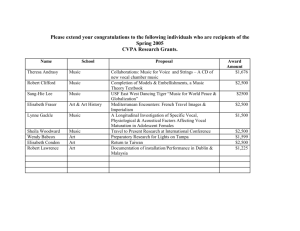

advertisement