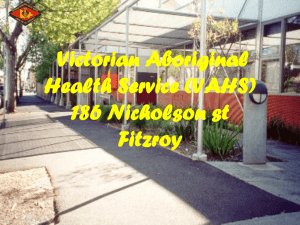

A HISTORY OF THE VICTORIAN ABORIGINAL HEALTH SERVICE

advertisement