The different types of tourists and their motives when visiting Alaska

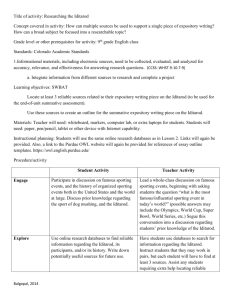

advertisement