Is the Capital Cost Allowance System in Canada Unnecessarily

advertisement

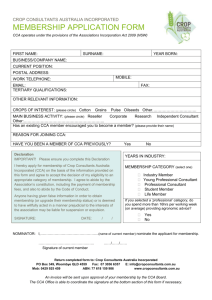

Issue in Focus Is the Capital Cost Allowance System in Canada Unnecessarily Complex? By Odette Pinto, PhD, MBA, CGA Commissioned by Rock Lefebvre, MBA, CFE, FCIS, FCGA About the Author Odette Pinto, PhD, MBA, CGA is an Assistant Professor of Accounting and Strategic Measurement with Grant MacEwan University. About CGA-Canada Founded in 1908, the Certified General Accountants Association of Canada (CGA-Canada) is a self-regulating, professional association of 75,000 Certified General Accountants (CGAs) and students. CGA-Canada develops the CGA Program of Professional Studies, sets certification requirements and professional standards, contributes to national and international accounting standard setting, and serves as an advocate for accounting professional excellence. CGA-Canada has been actively involved in developing impartial and objective research on a range of topics related to major accounting, economic and social issues affecting Canadians and businesses. CGA-Canada is recognized for heightening public awareness, contributing to public policy dialogue, and advancing public interest. For more information, contact can be made through: 100 – 4200 North Fraser Way, Burnaby, BC, Canada, V5J 5K7 Telephone: 604 669-3555 Fax: 604 689-5845 1201 – 350 Sparks Street, Ottawa, ON, Canada, K1R 7S8 Telephone: 613 789-7771 Fax: 613 789-7772 Electronic access to this report can be obtained at www.cga.org/canada ISSN 1925-1548 © By the Certified General Accountants Association of Canada, 2013. Reproduction in whole or in part without written permission is strictly prohibited. 2 Issue in Focus Is the Capital Cost Allowance System in Canada Unnecessarily Complex? April 2013 Introduction.................................................................................................................................4 Evidence of Increased Complexity of the CCA System..............................................................7 Impact of Book-Tax Differences and CCA Rules.......................................................................9 Use of the CCA System for Economic Incentives.......................................................................10 Departure from the Principles of the Income Tax System in Canada.........................................12 Does the Complexity Result in Costs and Inefficiencies?...........................................................13 Effects on International Competitiveness...................................................................................14 Conclusion and Recommendations.............................................................................................16 References...................................................................................................................................18 Is the Capital Cost Allowance System in Canada Unnecessarily Complex? 3 Introduction Recent tax literature and activism has called for tax reform that would lead to a more efficient income tax system in Canada, including tax policy research inviting a reduction in tax preferences to ensure that the system is fair and neutral (Bibbee, 2008; Mintz, 2007; Chen et al., 2007). On numerous occasions, advice from CGA-Canada has explicitly posited for simplification of the system. The purpose of this paper is to consider the Capital Cost Allowance (CCA) system in Canada in the spirit of investigating the extent to which it meets the principles of simplicity, equity and neutrality, assessing the effectiveness of economic incentives introduced through changes to the system, and to gauge how the CCA system affects the international competitiveness of Canadian businesses. Tax policy literature has expressed concerns about recurrent changes to the CCA system that have significantly increased its complexity while two important concerns are frequently raised in the literature: i) do CCA rates reflect economic reality, and ii) are the recurrent changes in CCA classes and rates effective in achieving the federal government’s policy objectives? This study examines these concerns and also investigates whether frequent changes to the CCA system result in unnecessary complexity that lead to incremental costs and inefficiencies for Canadian businesses. The CCA system was first introduced with the Income Tax Act of 1949, but substantially amended in 1972 and again in 1987. The system establishes the basis for the depreciation of capital property for tax purposes (Mida and Stewart, 1995), with an overall objective to ensure that all taxpayers benefit from a fair and equitable system for the depreciation of capital property. Over the years, the government has tailored the CCA system introducing changes in CCA classes, CCA rates, descriptions of the classes, and related provisions. Admittedly, the government’s practice of relying on the CCA system to achieve economic and other policy objectives has contributed to the increasing complexity of the system, with the changes introduced often deemed as neither fair nor neutral (Larter, 1988). For example, the government has introduced class and/or rate changes with a view to stimulate certain industries or activities during economic downturn. These changes are often seen as violating the principles of equity and neutrality as they are generally directed to targeted industries instead of being applied to all commercial activity or taxpayers. It is also uncertain whether these changes achieve the intended economic outcome or, instead, result in 4 Issue in Focus unnecessary complexity, violating the principle of simplicity. Other changes made to the CCA system to recognize the needs of specific industries and capital assets have often resulted in additional classes and/or lengthy descriptions for classes. It is also debatable whether this specificity is required. There are several characteristics that demonstrate the increase in complexity since the CCA system was first established: i) a significant increase in the number of CCA classes; ii) frequent changes to the CCA rates; iii) lengthy descriptions for classes; and iv) an introduction of CCA rules that many accounting professionals feel are unnecessary. In 1949, when the CCA system was introduced, 12 classes of assets were established; in 1972, the number of classes reached 28, in 1987 – 37, whereas currently, 56 classes exist. There have also been several CCA rate changes, with frequent changes for manufacturing and processing equipment and, more recently, changes to the classes and rates for computer hardware. The applicable classes for manufacturing equipment and computer hardware have been changed four times since 1972. Furthermore, the CCA rates have also changed with each of the class changes for both manufacturing and processing equipment, and computer hardware. The length of descriptions for several classes has grown substantially, as the government continues to refine the descriptions to achieve desired outcome. Complexity has been further exacerbated through the introduction of CCA provisions such as the ‘half-year’ and ‘available-for-use’ rules. For example, the ‘half-year’ rule, which was introduced with the 1981 tax reform, restricts the CCA that is allowed in the first year in which an asset is acquired. Many business representatives and accounting professionals have expressed frustration with this rule, citing it unnecessarily burdens the process and results in inefficiencies for Canadian businesses. The data for this research study has been obtained from a review of the tax literature, the income tax legislation and historical data on the CCA system. Views and evidence for this research study were obtained through consultations with accounting professionals at small, medium and large accounting firms, as well as representatives from various industries. Those consultations comprised of 15 participants from public accounting firms, including national and regional firms, and 14 participants from industry, including representatives from the manufacturing industry, served greatly to inform this paper. Consultations included both very specific (e.g. comments on the number of CCA classes) and broader questions (e.g. assessing the CCA system against the principles of the Canadian income tax system) that assisted in gathering views of participants. Is the Capital Cost Allowance System in Canada Unnecessarily Complex? 5 The findings of this research study provide evidence of the increased complexity of the CCA system. Consultations with accounting professionals suggest that the CCA system does not respect the key principles of a sound tax system such as simplicity, equity and neutrality. Furthermore, the CCA system often does not represent economic reality and the economic life of the underlying assets. However, a somewhat surprising result was that although accounting professionals perceive the CCA system to be cumbersome, and in need of adjustments, they also indicate that the increased complexity of the system does not appear to uniformly result in a disproportionate increase in costs. The results also indicate that for large businesses, the key most important characteristic of the CCA system is its international competitiveness; this is particularly important for certain industries. For example, representatives from the manufacturing industry contend that incentives like the accelerated capital cost allowance (ACCA) rates are essential in maintaining the international competitiveness of Canadian manufacturing firms. Yet, such incentives do result in increased complexity of the CCA system, leading to a conflict between the principles of international competitiveness and simplicity. CGA-Canada and other organizations have repeatedly called for simplification of the income tax system. This paper contributes to this line of tax policy research by critically examining the CCA system and including the perspective of accounting professionals working in public accounting firms and industry. 6 Issue in Focus Evidence of Increased Complexity of the CCA System Two factors that provide evidence of the increased complexity of the CCA system are the significant increase in the number of CCA classes and the substantial increase in the length of descriptions for many classes. Increase in the number of CCA classes The chart below illustrates the increase in the number of classes, from 12 classes in 1949 to 56 classes in 2012. Figure 1: Number of CCA Classes 60 Number of Classes 50 40 30 20 10 0 1953 1963 1973 1983 1993 2003 2012 A number of reasons may exist for introducing a new CCA class. A separate class is sometimes created to change or clarify the description (e.g. the type of buildings in Classes 3 and 6), or to change the CCA rate (e.g. manufacturing equipment in Classes 29, 39 and 43). A review of the class for Buildings illustrates the increase in the number of classes, as the designated class for Buildings has changed from Class 6 (prior to 1979) to Class 3 (from 1979 to 1987) to Class 1 (from 1987 onwards). The tax authorities have also created CCA classes to meet the needs of specific industries. For example, Class 42 was created especially to include fiber optic cables. Other classes have been created to facilitate policy initiatives; for example Classes 43.1 and 43.2 relate to renewable energy and energy efficient equipment. The question may be posed whether these classes are necessary. Is the Capital Cost Allowance System in Canada Unnecessarily Complex? 7 Many accounting professionals that participated in the consultation indicated that the presence of the large number of classes, including many redundant classes, makes the CCA system cumbersome and complex, and adds to the time and effort required to identify the appropriate class for an asset acquisition. However, public accounting firms serving small businesses do point out that small businesses generally use more common CCA classes; as such, the excessive variety of classes does not affect or impact businesses on a regular or uniform basis. Accounting professionals also underscored that the overlap in classes makes it difficult to identify the class for some asset acquisitions. For example, both accounting professionals and industry representatives point to confusion in the descriptions for manufacturing equipment and the overlap between Classes 29 and 39. Overall, the accountants recommend consolidation of redundant classes and the elimination of overlap in some class descriptions, which would reduce inefficiencies and work toward simplification of the CCA system. Changes in CCA rates The introduction of new CCA classes often goes hand in hand with a change in CCA rates. It is unclear whether such changes are effective. For example, the general consensus among the accountants consulted is that frequent changes to the CCA class and applicable CCA rates for computer hardware introduced between 2009 and 2011 were not effective and did not meet the apparent purpose of stimulating businesses to purchase computers. Furthermore, temporary measures (e.g. the introduction of a 100% rate with no ‘half-year’ rule for computers purchased after January 27, 2009 and before February 1, 2011) are generally not considered to be effective. Descriptions of CCA classes A review of the descriptions of the CCA classes provides further evidence of the increase in complexity. The descriptions of the CCA classes are structured to address the needs of specific industries and contribute to unnecessary complexity. For example, Class 12 includes a description of china and tableware, which is specific to certain industries only. Some classes also make reference to other classes, for example, Class 39 for manufacturing equipment refers to the previous class, Class 29. Accounting professionals indicate that the underlying approach to descriptions in the CCA system makes them cumbersome, which together with the overlap in some class descriptions, results in inefficiencies and unnecessary allocation of time and effort. The length of descriptions for some classes has increased substantially. Those consulted point specifically to the descriptions of Classes 8, 10, 39, 43.1 and 43.2 as being too lengthy and cumbersome. For example, Class 8 is the “catch-all” class for assets that do not belong in any other class yet the description for this class is very long. Overall, consultations with accounting professionals and industry representatives suggest that the lengthy descriptions of classes often create challenges in identifying the correct class for asset acquisitions. A few participants concede that the specific descriptions are needed, but most of 8 Issue in Focus those consulted indicate that the lengthy descriptions for various classes are unnecessary and do result in inefficiencies and allocation of additional time and effort including an increase in chargeable time at public accounting firms. Impact of Book-Tax Differences and CCA Rules Differences between the accounting and tax treatment of capital asset transactions result in book-tax differences. There are four important examples of such differences: i) differences in methods and rates between amortization (accounting) and CCA (tax); ii) differences in the recording of dispositions of capital assets; iii) the ‘half-year’ rule can be used for tax purposes but is not applicable for accounting purposes; and iv) the ‘available-for-use’ rule applies for tax purposes but not for accounting purposes. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) requires that amortization is based on the reasonable life of an asset, with appropriate matching in the allocation of capital costs against revenues. Anecdotal evidence suggests that businesses generally use the straight-line method for recording amortization for accounting purposes, but the amortization rates vary across businesses. The income tax system, in turn, uses a common method across all taxpayers in order to achieve fairness, and the declining balance method is the most common method used to calculate capital cost allowance for tax purposes. The grouping of assets into classes with common tax CCA rates is also essential in order to achieve consistency and comparability (which are attributes of fairness and equity) across taxpayers. Another difference between the accounting and tax systems occurs on the disposition of capital assets. For accounting purposes, a gain or loss on the disposition of assets occurs when the proceeds of disposition exceed (gain) or are inferior (loss) to the net book value of an asset, while for income tax purposes, a disposition of an asset results in the lesser of the proceeds of disposition or the original cost of the asset being deducted from the undepreciated capital cost (UCC) of the applicable class. The ‘half-year’ rule was introduced in 1981. Prior to 1981, full CCA was calculated for all assets, including assets purchased later in a year. This was considered inadequate as it did not represent a proper “matching” of capital cost allocations based on asset use. Although accounting professionals indicate that the ‘half-year’ rule does not necessarily or uniformly result in a Is the Capital Cost Allowance System in Canada Unnecessarily Complex? 9 substantial increase in preparers’ time or costs requirements, many expressed a frustration with this rule, feeling that it adds an unnecessary layer of complexity to the CCA system that is already complex. The ‘available-for-use’ rule adds an additional layer of complexity to the CCA system as it requires capital assets to be ready and available for use before they can be recorded as an addition to a class. Those consulted point out that although this rule has been in place since 1990, Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) auditors very seldom check for compliance. In the opinion of many accounting professionals, this rule is unwarranted and unnecessary. Overall, accounting professionals suggest that book-tax differences do result in extra costs associated with additional time, effort and training. They recognize that some differences are necessary to achieve fairness and equity across or amongst taxpayers, and that improvements in technology have made the reconciliation processes easier while mitigating costs. Nevertheless, the majority of those consulted suggest that book-tax differences should be minimized whereas both the ‘half-year’ and ‘available-for-use’ rules are inadequate and add unnecessary complexity. Use of the CCA System for Economic Incentives An underlying objective of the Canadian income tax system is to achieve economic prosperity and growth. From time to time, the federal government uses the CCA system to foster economic policy initiatives, including those that stimulate certain industries during economic downturns or achieve other overall economic objectives. However, it remains ambiguous whether such changes achieve the expected economic outcomes or whether they result in an unnecessary increase in complexity in the already complex CCA system. Thus, the federal government is frequently faced with an important trade-off between the principles of economic growth and simplicity, fairness and neutrality in the income tax system. A key example of an economic initiative introduced by the federal government is the increase in CCA rates and introduction of accelerated CCA (ACCA) rates for manufacturing equipment. The federal government introduces changes to CCA classes and rates for manufacturing equipment to stimulate the manufacturing industry, for example during downturns in the Canadian economy. ACCA was introduced to assist the manufacturing industry economically and to ensure the international competitiveness of the industry. The ACCA has also been introduced for other industries, for example the oil and gas industries. 10 Issue in Focus Representatives from the manufacturing, oil and gas industries indicate that economic incentives, like those propped up by ACCA, are effective and essential. They emphasize that the ACCA makes major projects financially viable, as the projects undertaken are often costly and entail a long-term commitment, which also emphasizes the need for a long-term commitment from government authorities. Industry representatives also point to the industry’s effects on the Canadian economy in general – for example the manufacturing industry contributes substantially to employment in Canada. Another recent government initiative was a change in the CCA rate for computers, together with the waiving of the ‘half-year’ rule. This was a temporary incentive and was effective for a limited time period. The majority of accounting professionals consulted suggest that this incentive was not effective and, instead, it added a layer of complexity that resulted in additional time and effort – for example the time and effort to identify the specific dates of computer purchases. The majority of accounting professionals consulted feel that the introduction of accelerated CCA rates for computer purchases was not effective and did little to achieve the underlying objective of stimulating the purchase of computers and the information technology industry. Overall, accounting professionals and industry representatives conclude that most changes to the CCA system to stimulate a particular industry are ineffective as the purchase of capital assets is driven by business necessity and not by tax treatment. Therefore, the introduction of ACCA rates or other such initiatives may affect the timing of an asset acquisition but not the acquisition decision itself. Furthermore, accounting professionals at public accounting firms indicate that clients rarely have timely knowledge of such incentives. Thus, anecdotal evidence suggests that the introduction of ACCA rates, particularly for short periods of time, is ineffective. That said, certain industries (e.g. manufacturing, oil and gas) contend that the ACCA rates are essential for Canadian businesses to be internationally competitive; particularly with the United States. Yet, economic incentives favouring one industry at the exclusion of another can hardly be viewed as fair and equitable. Notwithstanding, consultations with accounting professionals and representatives of industries not affected by such incentives suggest that this inequity in the CCA system is not perceived as being unfair. The general perception among accounting and business representatives appears to be that such incentives are commonly accepted as being essential for certain industries – for example the manufacturing industry, during an economic recession. Is the Capital Cost Allowance System in Canada Unnecessarily Complex? 11 Departure from the Principles of the Income Tax System in Canada The fundamental principles outlined in the Carter Report (1966)1 continue to guide income taxation in Canada – neutrality, equity (fairness), simplicity and international competitiveness (Hogg et al., 2010). In this section, the CCA system is examined to assess how it measures up to each of these principles. Neutrality: The prescription of a specific method for CCA and specific rates for each prescribed CCA class minimizes the range of amortization alternatives, and this is intended to be “neutral” and “fair” to all taxpayers. However, as the CCA system does influence capital asset and investment decisions it is not really “neutral”. Furthermore, as the CCA system is used, from time to time, to provide economic incentives to stimulate certain industries (e.g. the manufacturing industry during a recession) it does affect business decisions and therefore cannot be considered perfectly “neutral”. Equity (fairness): The CCA system is used to support economic initiatives and to achieve other economic policy objectives. For example, accelerated CCA rates are provided to certain industries to the exclusion of others, so this cannot be considered “fair” to all taxpayers. Another example relates to the use of the asset. For example, the CCA system can be considered inequitable if one business employs an asset 24 hours per day while another business uses the same asset for only a few hours per day, yet the asset receives the same treatment in both businesses. Simplicity: Most accounting professionals consulted agree that the CCA system is complex, yet the majority of those consulted seem to have accepted the complexity, assenting that this complexity is perhaps necessary to ensure fairness and equity. However, the accountants consulted do suggest that the CCA system needs to be modernized and recommend a review of the system, to eliminate redundancies, and to consolidate some classes in favour of moving toward simplification. International competitiveness: This appears to be the most important principle for certain industries; for example the manufacturing, oil and gas industries. These industries emphasize the need for long-term assurance and stability in the CCA rates to make costly and long-term projects viable. These industries also point to the importance of comparability of CCA methods and rates to those of other countries, particularly the United States, to maintain the international competitiveness of Canadian businesses. 1 The Carter Report has not been published by the Canadian government (Hogg et al., Principles of Canadian Income Tax Law, 2010). 12 Issue in Focus It is widely accepted that there are conflicts and trade-offs between the principles. For example, neutrality suggests that the income tax system should not drive business decisions but as the government uses income taxation to achieve economic stabilization and growth, changes to the tax legislation are occasionally introduced to affect business decisions (e.g. to stimulate a specific industry). This violates the principle of neutrality and, furthermore, it also violates the principle of fairness as it is not fair and equitable to all taxpayers. Concurrently, economic initiatives implemented using the CCA system could be considered necessary for economic stabilization and growth. The principle that is viewed as the most important and overarching may change and evolve over time. For example, with globalization and global competition, the principle that is currently of critical importance to certain industries is naturally international competitiveness. The extant literature (Chen and Mintz, 2009) has called for a CCA system that represents the economic reality of the underlying assets. However, accounting professionals and industry representatives indicate that, in most cases, CCA does not reflect the economic life of an asset and does not represent a matching of the capital cost of assets to its business use. Furthermore, in most cases, CCA results in a quicker write-off of capital costs than the life and use of the underlying assets in a business. Overall, accounting professionals consulted indicate that the government should avoid unnecessary complexity and maintain a system that is as simple as possible. Does the Complexity Result in Costs and Inefficiencies? Tax policy research (Mintz, 2007) has emphasized the importance of simplicity, as complexity that results in additional costs affects the profitability and international competitiveness of Canadian businesses. Literature suggests that unnecessary complexity of the CCA system affects business decision-making and could result in additional costs and inefficiencies, as the decision makers must understand the CCA system in order to make appropriate decisions related to the acquisition and disposition of capital assets; as such, complexity adds to the time and effort of decision-making. Accounting professionals and industry representatives concur that the level of complexity of the CCA system has increased, pointing to the expansion in the number of classes, the lengthy descriptions and rules like the ‘half-year’ rule as examples of such complexity. Consultations with accounting professionals indicate that the CCA system needs to be thoroughly reviewed to Is the Capital Cost Allowance System in Canada Unnecessarily Complex? 13 eliminate redundancies (e.g. in the CCA classes), to consolidate and shorten the length of descriptions for many CCA classes and to critically assess the need in some of the rules that add to the complexity (e.g. the ‘half-year’ and ‘available-for-use’ rules). In general, accounting and industry representatives indicate that the CCA system should not be the vehicle used for introducing economic incentives as most temporary incentives are ineffective and yet add unnecessary complexity. Overall, accounting and business representatives agree that the CCA system is in need of an overhaul to consolidate and simplify the system. Anecdotal evidence obtained from representatives of accounting firms and industry suggests that although there has been a definite increase in complexity in the CCA system over the past two decades and that there is a need for consolidation and simplification to increase efficiency and fluidity, they have in part been successful in offsetting substantial cost or fee increases, through automation and improved practices. Effects on International Competitiveness Tax policy research has emphasized the importance of ensuring that the income tax system supports international competitiveness of Canadian businesses (Mintz, 2007) and ensures Canada’s attractiveness as a place to invest (Bibbee, 2008). The federal government’s Economic Action Plan and recent budgets have also stressed the importance of competitiveness (Pankratz 2010; Pankratz, 2011). The existing literature also indicates that the tax system should be simplified, as complexity leads to inefficiencies that affect the competitiveness of Canadian businesses. Accounting professionals and industry representatives are in agreement that the CCA system is unnecessarily complex and needs an overhaul. Although accountants appear to accept the CCA system as it is and have mitigated substantial cost increases, they do agree that a simplified system would reduce inefficiencies and would benefit Canadian businesses. International competitiveness is not a major factor for small and mid-size businesses, but it is a key issue facing large businesses with global operations particularly in certain industries such as manufacturing, oil, gas, and pipeline industries. For example, representatives from the manufacturing industry point to competition from businesses in the United States and assert that it is critically important that the Canadian CCA system provides incentives similar to those of the United States in order to ensure a level playing field for Canadian manufacturing. Maintaining comparability with the United States is a key reference point for tax initiatives (Bibbee, 2008). Furthermore, other economic factors such as exchange rate fluctuations are also a major factor in assessing the international competitiveness of Canadian manufacturing businesses. Representatives from the manufacturing industry point to the effects of exchange rates shocks on the industry and the need for tax initiatives to offset these effects. 14 Issue in Focus In recent years, the federal government has moved toward the use of temporary ACCA rates. Budget 2010 introduced ACCA for certain types of clean energy generation and conservation equipment. Prior budgets have also introduced ACCA for manufacturing equipment and for certain capital expenditures incurred by the oil sands industry. Furthermore, Budget 2011 and Budget 2013 both extended the ACCA for machinery and equipment used in the manufacturing industry; Budget 2011 also expanded the types of clean energy equipment eligible for ACCA (Pankratz, 2010; Pankratz, 2011). Yet, economists have called for the elimination of the ACCA and the tax advantages to oil sand projects as they do not work toward achieving sustainability in the energy sector (Mourougane, 2008) and could result in overheating of the sector and the surrounding economy. The long-term effectiveness of such incentives should also be considered as such temporary measures may work in the short-term but could reduce capital investment in the future (Chen and Mintz, 2009), affecting international competitiveness in the long-term. Furthermore, such preferences depart from the principles of fairness and neutrality. During the consultations, many accounting and industry representatives questioned whether the use of the CCA system and ACCA rates are the appropriate methods for maintaining international competitiveness in these industries. For example, some representatives from the manufacturing industry suggest that the use of investment tax credits would be more appropriate and more effective. Others suggest that the use of grants may be more adequate, as it would make businesses more accountable for the government incentives received (Bibbee, 2008). Is the Capital Cost Allowance System in Canada Unnecessarily Complex? 15 Conclusion and Recommendations The purpose of this research study has been to critically examine the CCA system in Canada. The research findings provide evidence of the increased complexity of the CCA system, with significant increases in the number of CCA classes and the length of descriptions of several CCA classes, as well as the introduction of rules like the ‘half-year’ rule and ‘available-foruse’ rules that add an additional layer of complexity to an already complex CCA system. An assessment of the CCA system against the underlying principles of Canada’s income tax system indicates that the system falls short on several principles and, in particular, the current system conflicts with the principles of simplicity, equity and neutrality, and does not properly reflect economic reality. The federal government has tampered with the CCA system for economic stabilization; particularly economic incentives during recessions or incentives to stimulate a particular industry. Views gathered through consultations with accounting professionals and industry representatives indicate that the use of the CCA system for economic incentives is generally not effective, particularly as the purchase of capital assets is argued to be founded in business decisions rather than in tax decisions; and that such incentives create unnecessary complexity. However, representatives from certain industries (e.g. manufacturing, oil and gas) emphasize the importance of such incentives for the industry to retain international competitiveness and to offset exchange rate shocks. It is nonetheless questionable whether the use of the CCA system to achieve economic stimulation is advisable, particularly as it results in increased complexity within a system that instigates inefficiencies. Accountants and industry representatives suggest that alternative methods may be more effective for these industries, for example the use of investment tax credits or government grants. The costs and benefits of such alternate methods should be assessed. Future research could compare the effectiveness of using ACCA or Investment Tax Credits, and could also examine and reassess the Scientific Research and Experimental Development (SR&ED) tax incentive program to determine if it could be more accessible, relevant, and advantageous to Canadian businesses. Future research could also examine the effectiveness of using grants during economic downturns or to stimulate a particular industry. Mourougane (2008) suggests that grants would be a more accountable form of incentives to an industry. International competitiveness is of critical importance in a global economy and particularly important to Canadian businesses and resources. Future research could critically examine the factors that affect the international competitiveness of Canadian businesses, particularly industries that are in close competition with the United States. Consultations with accounting 16 Issue in Focus professionals and representatives from certain industries (e.g. manufacturing, oil and gas) suggest that this should be the most important principle of the income tax system, as international competitiveness is of critical importance to the long-term success of Canadian businesses. An important principle of the Canadian income tax system has long been simplicity. Future research could extend this line of consideration by examining other areas of unnecessary complexity that lead to inefficiencies in the income tax system that affects the profitability, sustainability, and competitiveness of Canadian businesses. But in order to successfully do so, we should probably agree from the outset that the tax regime is hardly simple… Is the Capital Cost Allowance System in Canada Unnecessarily Complex? 17 References Bibbee, A. 2008. Tax Reform for Efficiency and Fairness in Canada. OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 631, OECD publishing, OECD. CGA-Canada. 2007. Paving the Way to Prosperity: It’s Time for Real Tax Reform, a submission to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Finance. CGA-Canada, Letter to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Finance on the structure of Canada’s revenue-raising system. June 4, 2008. CGA-Canada. CGA-Canada, Pre-Budget Submission to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Finance. August 14, 2009. CGA-Canada. Chen, D. and J. Mintz. 2009. The Path to Prosperity: Internationally Competitive Rates and a Level Playing Field. C.D. Howe Institute, Commentary No. 295. Chen, D., J. Mintz and A. Tarasov. 2007. Federal and Provincial Tax Reform: Let’s Get Back on Track. C.D. Howe Institute, Backgrounder No. 102. Hogg, P., J. Magee and J. Li. 2010. Principles of Canadian Income Tax Law, 7th edition. Carswell, Thomson Professional Publishing. Larter, R. 1988. Capital Cost Allowance and Eligible Capital Property: Tax Reform Implications. Canadian Tax Foundation, 1988 Conference Report. Mida, I. and K. Stewart. 1995. The Capital Cost Allowance System. Canadian Tax Journal, 43(5), 1245 – 1264. Mintz, J. M. 2006. 2006 Tax Competitiveness Report: Proposals for Pro-Growth Tax Reform. C.D. Howe Institute, Commentary No. 239. Mintz, J. M. 2007. 2007 Tax Competitiveness Report: A Call for Comprehensive Tax Reform. C.D. Howe Institute, Commentary No. 254. Mourougane, A. 2008. “Achieving Sustainability of the Energy Sector in Canada”. OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 618, OECD Publishing, Paris. 18 Issue in Focus Pankratz, A. 2010. 2010 Canadian Federal Budget. Journal of International Taxation, July 2010, 52- 60. Pankratz, A. 2011. 2011 Canadian Federal Budget. Journal of International Taxation, June 2011, 51- 60. Stikeman Income Tax Acts, Annotated. Carswell, Toronto Is the Capital Cost Allowance System in Canada Unnecessarily Complex? 19