Researching People: The Collaborative Listener

advertisement

5

Researching People:

The Collaborative Listener

Portraying people depends on careful

listening and observing. In this chapter you

will learn to:

• use details to describe people

•

gather information from informants

• transcribe others' conversation

• borrow elements of fiction writing

Researching people means stepping in to the worldviews of others. When we

talk with people in the field or study the stuff of their lives-their stories, artifacts, and surroundings-we enter their perspectives by partly stepping out of

our own.

In an informal way, you are always gathering data about people's backgrounds and perspectives~their worldviews. "So where are you from?" "How

do you like it here?" "Did you know anyone when you first came here?" Not only

do you ask questions about people's backEthnography is interaction, collaboration.

grounds, but you also notice their artifacts

What it demands is not hypotheses,

and adornments-the things with which

which may unnaturally close study down,

they represent themselves: T-shirts, jewelry,

obscuring the integrity of the other, but

particular kinds of shoes or hairstyles. The

the ability to converse intimately.

speculations and questions we form about

-HENRY CLASSIE

others cause us to make hypotheses about the

people we meet. We may ask questions, or we may just listen. But unless we

listen closely, we'll never understand others from their perspectives. We need to

know what it's like for that person in this place.

Even in an informal conversation, we conduct a kind of ethnographic inter~

view. Good interviewing is collaboration between you and your informant, not

very different from a friendly talk. Listening to your relatives share stories at a

wedding, pouring over a photo album with your grandmother, and gossiping

about old times at a school reunion are all instances in which you can gather data

through collaborative listening. You've experienced your local media interviewing

219

220

Chapter 5

Researching People: The Collaborative Listener

sports heroes and newsworthy citizens, and you know famous television and

radio interviewers such as Oprah, Barbara Walters, and Charlie Rose. Your

fieldworking interviews might employ the same skills: establishing rapport, letting your informant digress from your questions, as well as carefully listening

and navigating the conversation process.

This chapter will help you strengthen the everyday skills of listening, questioning, and researching people who interest you. You'll experience interactive

ways to conduct interviews and oral histories. You'll look for and discover

meaning in your informants' everyday cultural artifacts. You'll gather, analyze,

write, and reflect on family stories. And you'll read some examples of how other

fieldworkers have researched and written about people's lives.

The Interview: Learning How to Ask

Fieldworkers listen to and record stories from the point of view of the informant- not their own. Letting people speak for themselves by telling about

their lives seems an easy enough principle to follow. But in fact, there are some

important strategies for both asking questions and listening to responses. Those

strategies are part of interviewing - learning to ask and learning to listen.

Interviewing involves an ironic contradiction: you must be both structured

and Hexible at the same time. While it's critical to prepare for an interview with a

list of planned questions to guide your talk, it is equally important to follow your

informant's lead. Sometimes the best interviews come from a comment, a story,

an artifact, or a phrase you couldn't have anticipated. The energy that drives a

good interview-for both you and your informant-comes from expecting the

unexpected.

Expecting the Unexpected It's happened to both of us as interviewers. As

part of a two-year project, Elizabeth conducted in-depth interviews with Anna,

a college student who was a dancer. Anna identified with the modern dancers at

the university and also was interested in anin1al rights, organic foods, and ecological causes. She wore a necklace that Elizabeth thought served as a spiritual

talisman or represented a political affiliation. When she asked Anna about it, she

learned that the necklace actually held the key to Anna's apartment-a much

less dramatic answer than Elizabeth anticipated. Anna claimed that she didn't

trust herself to keep her key anywhere but around her neck, and that information provided a clue to her temperament that Elizabeth wouldn't have known if

she hadn't asked and had persisted in her own speculations.

In a shorter project, Bonnie interviewed Ken, a school superintendent, over

a period of eight months. As Ken discussed his beliefs about education, Bonnie

connected his ideas with the writings of progressivist philosopher John Dewey.

At the time, she was reading educational philosophy herself and was greatly

influenced by Dewey's ideas. To her, Ken seemed to be a contemporary incarnation of Dewey. Eventually, toward the end of their interviews, Bonnie asked

The Interview: Learning How to Ask

md

our

letting

JeS-

tive

)Ver

yze,

ther

iforJout

ome

1ose

.ired

itha

your

tory,

a

res

~the

s. As

.nna,

:rs at

eco'itual

:, she

nu ch

lidn't

rmawnif

over

)nnie

~wey.

·eatly

ncar;sked

Ken which of Dewey's works had been the most important to him. "Dewey?" he

asked. "John Dewey? Never exactly got around to reading him."

No matter how hard we try to lay aside our assumptions when we interview others, we always carry them with us. Rather than ignore our hunches, we

need to form questions around them, follow them through, and see where they

will lead us. Asking Anna about her necklace, a personal artifact, led Elizabeth

to new understandings about Anna's self-concept and habits that later became

important in her analysis of Anna's literacy. Bonnie's admiration for Dewey had

little to do directly with Ken's educational philosophy, but her follow-up questions centered on the scholars who did shape Ken's theories. It is our job to

reveal our informant's perspectives and experiences rather than our own. And

so our questions must allow us to learn something new, something that our

informant knows and we don't. We must learn how to ask.

Asking

Asking involves collaborative listening. When we interview, we are not extracting information the way a dentist pulls a tooth, but we make meaning together

like two dancers, one leading and one following. Interview questions range

between closed and open .

Closed Questions Closed questions are like those we answer on application

forms or in magazines: How many years of schooling have you had? Do you

rent your apartment? Do you own a car? Do you have any distinguishing birthmarks? Do you use bar or liquid soap? Do you drink sweetened or unsweetened

tea, caffeinated or decaffeinated coffee? Some closed questions are essential for

gathering background data: Where did you grow up? How many siblings did

you have? What was your favorite subject in school? But these questions often

yield single phrases as answers and can shut down further talk. Closed questions can start an awkward volley of single questions and abbreviated answers.

To avoid asking too many closed questions, you'll need to prepare ahead of

time by doing informal research about your informants and the topics they represent. For example, if you are interviewing a woman in the air force, you may

want to read something about the history of women in aviation. You might also

consult an expert in the field or telephone government offices to request informational materials so that you avoid asking questions that you could answer for

yourself, like "How many years have women been allowed to fly planes in the

U.S. Air Force?" When you are able to do background research, your knowledge

of the topic and the informant's background will demonstrate your level of interest, put the informant at ease, and create a more comfortable interview situation.

Open Questions Open questions, by contrast, help elicit your informant's

perspective and allow for a more conversational exchange. Because there is no

single answer to open-ended questions, you will need to listen, respond, and

follow the informant's lead. Because there is no single answer, you can allow

221

222

Chapter 5

Researching People: The Collaborative Listener

yourself to engage in a lively, authentic response. In other words, simply being

interested will make you a good field interviewer. Here are some very general open

questions-sometimes called experiential and descriptive-that encourage the

informant to share experiences or to describe them from his or her own point

of view.

....................................................................................................................

Open Questions for Your Informant

Ii!

Tell me more about the time when ...

0

Describe the people who were most important to ...

&

Describe the first time you ...

0

Tell me about the person who taught you about. ..

0

What stands out for you when you remember ...

•

Tell me the story behind that interesting item you have.

@

Describe a typical day in your life.

®

How would you describe yourself to yourself?

0

How would you describe yourself to others?

....................................................................................................................

When thinking of questions to ask an informant, make your informant your

teacher. You want to learn about his or her expertise, knowledge, beliefs, and

worldview.

Box20

Using a Cultural Artifact in an Interview

iQt!l@•D

This exercise mirrors the process of conducting interviews over time with an informant.

It emphasizes working with the informant's perspective, making extensive and accurate

observations, speculating and theorizing, confirming and disconfirming ideas, writing up

notes, listening well, sharing ideas collaboratively, and reflecting on your data.

To introduce interviewing in our courses, we use an artifact exchange. This exercise

allows people to investigate the meaning of an object from another person's point

of view.

>ly being

'falopen

rage the

.vn point

eite1~1

choose a partner from among your colleagues. You will act as both interviewer and inforR

mant. Select an interesting artifact that your partner is either wearing or carrying: a key

chain, a piece of jewelry, an item of clothing. Both partners should be sure the artifact is

one the owner feels comfortable talking about. If, for example, the interviewer says, 11 Tell

..........

me about that pin you are wearing," but the informant knows that her watch has more

meaning or her bookbag holds a story, the interviewer should follow her lead. Once

you've each chosen an artifact, try the following process. Begin by writing observational

and personal notes as a form of background research before interviewing:

1.

Take observational notes. Take quiet time to inspect, describe, and take notes on

your informant's artifact. Pay attention to its form and speculate about its function.

Where do you think it comes from? What is it used for?

2.

Take personal notes. What does it remind you of? What do you already know about

things similar to it? How does it connect to your own experience? What are your

hunches about the artifact? In other words, what assumptions do you have about it?

(For example, you may be taking notes on someone's ring and find yourself speculating about how much it costs and whether the owner of the artifact is wealthy.) It is

important here to identify your assumptions and not mask them.

3.

Interview the informant. Ask questions and take notes on the story behind the

artifact. What people are involved in it? Why is it important to them? How does the

owner use it? Value it? What's the cultural background behind it? After recording

your informant's responses, read your observational notes to each other to verify or

clarify the information.

4.

Theorize. Think of a metaphor that describes the object. How does the artifact reflect

something you know about the informant? Could you find background material

about the artifact? Where would you look? How does the artifact relate to history or

culture? If, for example, your informant wears earrings made of spoons, you might

research spoon making, spoon collecting, or the introduction of the spoon in polite

society. Maybe this person had a famous cook in the family, played the spoons as a

folk instrument, or used these as baby spoons in childhood.

5.

Write. In several paragraphs about the observations, the interview, and your theories,

create a written account of the artifact and its relationship to your informant. Give a

draft to your informant for a response.

6.

Exchange. The informant writes a response to your written account, detailing what

was interesting and surprising. At this point, the informant can point out what you

didn't notice, say, or ask that might be important to a further understanding of the

artifact. You will want to exchange your responses again, explaining what you learned

from the first exchange.

7.

Reflect. Write about what you learned about yourself as an interviewer. What are your

strengths? Your weaknesses? What assumptions or preconceptions did you find that

you had that interfered with your interviewing skills? How might you change this?

8.

Change roles and repeat this process.

............

ant your

.efs, and

>p

•

223

Box20

continued

Lini Ge's Watch

Although we've done this exercise with many people-students, teachers, and

researchers-we're always surprised at the flood of cultural information that comes from

the pages people fill during their interviews. We both enjoy practicing interviewing with

artifacts, so we almost always participate in the process. Here's an interview Bonnie did

with her student Lini Ge:

When Lini handed me her watch, my first reaction was "Oh, she's a swimmer or some

other kind of an athlete." I noticed it was made out of a black, supple, strong, rubbery, plastic kind of material. It's very colorful and it says "sports watch" in yellow and

"water resistant" in purple on the strap.

There are three elliptical openings on either side of the strap, about three inches

on each side, suggesting, too, another kind of practical water resistance. "It's an ugly

belt," she tells me. "Do you call it a belt?" "Oh, strap," I answer; "it looks Ike a belt; it

has a black buckle, but I guess because you wear it on your wrist you call it a strap,"

and l realize it's yet another American synonym that would make no sense to a native

speaker of another language. It is, basically, a belt. Lini has owned it since her aunt in

Beijing gave it to her almost a decade ago, and she had to replace the strap when the

original one broke. She liked that strap better; it was black leather. I noticed that the

new strap has nine holes. When I had been a tourist in China, I learned the spiritual

and historical importance of the number 9. Lini laughed when l asked her about that

and said she'd never even bothered to count how many holes her watch strap had. I

realize it's the company's way to accommodate many sizes of wrists.

But truth to tell, such complicated watches scare me. l grew up on the old-fashioned

wind-up watch with a traditional face, and although I do love battery power, I still

prefer a round two-hand dial. My daughter changes all of my digital docks twice a year

because I find it so frustrating. But obviously, since Lini is a member of the high-tech

generation, all of the buttons and features would not be a problem for her. The mechanism and face are practical and complex, too, a slightly exaggerated square-about

1" x 1.3"-with many color-coded features, inside and outside of a thin red border.

She keeps the watch set to twenty-four-hour time, the convention used in China

(it is 18:20:54 when I observe it; 6:20 p.m. in American convention). But it's really not.

"I keep it about five minutes fast," she tells me. "I don't want to miss my bus, and I'm

always running behind." A critical skill for any student.

Lini has Lupus, I remember, a chronic illness. She also has problems with her

kidneys. Disease has changed the course of her life and studies. The more I observed

the watch before I talked with her, the more I realized that a major function for her

would be that she could keep track of her blood pressure-conveniently on her wrist

while also telling the time. Outside the border, there are four buttons, two on each

side. On the left, there is "adjust" and "mode," for keeping time. On the right, a black

button is labeled "bp start" and a yellow one labeled "restart." On the upper portion

of the face, aside the CASIO company logo, are the words "Blood Pressure Monitor"

and BP-120 (a model number, but ironically, the number of healthy blood pressure).

A yellow panel offers the day, the date, and a small red heart. The time is displayed

digitally: hour, minutes, and seconds. On the lower portion are the words "systolic"

224

and "diastolic," as well as what appears to be a sensor light on one side and a panel

that proclaims 11 pls" and "ekg." Aha. Medical terms about blood pressure.

I am intrigued that it's a Japanese watch with English language labels, owned by

a Chinese woman who got it as a gift from an aunt who doesn't speak English. It is

a symbol of our global economy, our multinational world. I assumed wrongly that

Lini must have bought it in the United States. "Oh, a Chinese person would buy this

watch this way," Lini told me. 11 Casio is a famous brand, and it's more convenient to

use these terms." Her friends in China were fascinated by the watch's special features, although Lini admits it isn't that convenient for its medical value. She quickly

discovered that the blood pressure features will only work with fresh batteries. But

her friends enjoyed taking their heartbeats and blood pressure with it. She hasn't yet

shared it with her U.S. friends. I want to buy her some fresh batteries and check to

see if it works for me!

I

I

Ii

~

I

In interviews, researchers sometimes use cultural artifacts to enter into the

informant's perspective. We might start by talking about something in our informant's environment: a framed snapshot, a CD or DVD collection, an interesting or unusual object in the roo1n-anything that will encourage co1nfortable

conversation. When we invite informants to tell stories about their artifacts,

we learn about the artifacts themselves (Lini Ge's watch) and, indirectly, about

other aspects of their world that they might not think to talk about. Artifacts,

like stories, can mediate between individuals and their cultures.

Learning How to Listen

Although most people think that the key to a good interview is asking a set of

good questions, vve and our students have found that the real key to interviewing

is being a good listener. Think about your favorite television or radio talk show

personalities. What do they do to make their informants comfortable and keep

conversation flowing? Think about someone you know whon1 you've always

considered a good listener. Why does that person make you feel that way?

Good listeners guide the direction of thoughts; they don't interrupt or move

conversation back to the1nselves. Good listeners use their body language to let

informants understand that their informants' words arc important to the1n, not

allowing their eyes to wander, not fiddling, not checking their watches or their

phones. They encourage response with verbal acknowledgments and follow-up

questions, with embellishments and examples.

To be a good listener as a field interviewer, you must also have structured

plans with focused questions. And you must be willing to change them as the

225

226

Researching People: The Collaborative Listener

Chapter 5

conversation moves in different directions. With open qt1estions, background

research, and genuine interest in your informant, you'll find yourself holding

a collaborative conversation from which you'll both learn. It is the process, not

the preplanned information, that n1akes an interview successful.

......................................................................................................, .............

Etiquette for Conducting an Interview

In addition to preparing yourself with guiding questions and good listening

habits, here are some basic rules of etiquette for conducting a successful inter~

view. Always keep in mind that you are using someone's time.

'*

Arrange for the interview at your informant's convenience. Your inter~

view should fit into that person's schedule, not vice versa. Put his or her

needs first.

®

Explain your project in plain language that your informant will understand.

Don't bore or scare them with insider expressions such as "ethnographic"

or 11 fieldsite research."

•

Agree on a quiet place to talk. Avoid places like cafes that have a lot of

ambient noise.

©

Arrive on time and be prepared. Make sure your equipment works (pens,

batteries, recording devices}. Have your questions and notepad ready.

©

Dress appropriately for the setting and for your informant. You'd wear

something different to interview a lifeguard on the beach than your grandmother in her living room.

®

Don't try to squeeze too much into a short time. Be sensitive to social cues

and, if necessary, arrange for an additional interview.

®

Thank your informant and follow up with a thank-you note, e-mail, or, if

appropriate, a token of gratitude.

....................................................................................................................

A Successful Interview

Paul Russ conducted illterviews with five AIDS survivors for an ethnographic

film, Healing without a Cure: Stories of People Living with AIDS, sponsored by a

local health agency. He developed a list of open and closed questions to prepare

for and guide his interviewing process. He knew that closed questions would

provide him with similar baseline data for all of his informants. For this reason,

he formulated some questions that had one specific answer:

Paul's Closed Questions

®

"How many months have you lived with your diagnosis?"

®

"When did you first request a 'buddy' from the health service?"

®

"Does your family know about your diagnosis?"

Learning How to Listen

nd

ng

10t

But the overall goal of his project was to capture how individuals coped with

their diagnoses daily, drawing on their own unique resources. He wanted to

avoid creating a stereotypical profile of a "day in the life of a person living with

AIDS" since he knew that no one AIDS patient's way of coping could represent

all other patients' coping styles. Paul constructed open questions to allow his

informants to speak from their lived experiences.

Paul's Open Questions

®

"What did you already know ahout AIDS when you were diagnosed?"

•

"How did others respond to you and your diagnosis?"

©

"What has helped you most on a day-to-day basis to live with the virus?"

©

"Have people treated you differently since you were diagnosed?"

In the following excerpt from his hundreds of pages of transcripts, Paul

talks with Jessie, a man who had been living with his diagnosis for eight years.

For Paul, this interview was a struggle because Jessie hadn't talked much with

others about AIDS. And because Paul chose to study people whose lives were

very fragile, he paid particular attention to the interactive process between

himself and his informants. In the following transcript, Paul uses Jessie's dog,

Princess, just as another interviewer might have used an artifact to get further

information:

P:

J:

iic

I

a

Lre

1ld

m,

P:

J:

What was your reaction when you were first diagnosed?

(This is one of the questions Paul posed to each of his five

informants. Because he was making a training film for public

health volunteers, he wanted to record people's initial reactions on

discovering that they had a publicly controversial illness.)

My first reaction? How am I going to tell my family. And I put it in

my mind that I would not tell anyone until it became noticeable.

And I wondered who would take care of me .... I knew sometimes

AIDS victims go blind. I panicked a little bit, and I started thinking

of all the things I have to do to make my life livable .... I started

thinking about the things I could do to make it go easier. And I

started thinking of things I would miss.

Like Princess, your dog?

(Paul knew froni previous talks that Jessie's dog was an important

part of his daily life.)

I've had Princess for three years. I had another red dachshund,

but she got away. I got Princess as a Christmas gift .... She

comforts me. She knows when I'm not feeling right. She comes

and rubs me. She goes places with me. If I'm in the garden,

she's right there. She can't let me out of her sight. Sometimes

227

228

Chapter 5

Researching People: The Collaborative Listener

I talk to her, late at night, we just lay there. She seems like

she understands .... I don't think she can live without me. If

something happens to me, she'll be so confused. I think she'll be

so lonely, she'll go off somewhere and just die .... I want to give

her to somebody. Maybe an older person, someone I believe will

take care of her.

(By talking about his dog, Jessie opened himself up to Paul. By

folloiving up on Jessie's comment about "things he'd nziss," Paul

deepened their interaction and intensified their talk. It was not the

dog herself that was important in this exchange but what Princess

represented fro1n Jessie's perspective. Paul did not intend to make

Jessie talk about his fear of dying, but it happened naturally as

he talked about Princess. At this point, Paul found a way to ask

another one of the prepared questions that he used with each

of his informants. And Jessie's answer brought them back to

Princess.)

P:

What's your typical day like?

J:

My typical day is feeding Princess, letting her out, doing my

housework. I like to do my work before noon because I'm addicted

to soap operas .... I like to work in the yard. I've got a garden. I

have some herbs. And I like every now and then to pray. I go to the

library. I do a great deal of reading.

(Paul continued to interview Jessie about his spirituality and his

reading habits. He brought this interview around to another preplanned question that he asked of all his AIDS infonnants.)

P:

What advice do you have for the newly diagnosed?

J:

Don't panic. You do have a tendency to blow it out of proportion.

And find a friend, a real friend, to help you filter out the negative.

Ask your doctor questions. Let it out and forgive. Forgive yourself,

you're only human. And forgive the person you think gave it to you.

Then you will learn that the key to spirituality is to abandon

yourself .... I don't want a sad funeral. I want music, more music

than anything e!Se. I don't want my family to go under because of

this disease.

Paul's interviews eventually became a training fihn for volunteers al the

Triad Health Project and area schools that wanted to participate in AIDS support and education. In the film, Paul has the advantage of presenting his data,

not just through verbal display but visually as well. As Paul conducts his interviews, we hear his voice and see his informants-their surroundings and artifacts, their gestures and body language, and the tones of voices as they respond

to Paul.

Box21

Establishing Rapport

Paul Russ worked hard to establish rapport with his informant. Rapport doesn't happen

in one short interview. Interviewing is a collaborative and interactive process in which

researchers make themselves knowledgeable about their informants' positions, interests,

feelings, and worldviews.

In this activity, you will reflect on your relationship with an informant and gain greater

understanding of yourself as a researcher. Write a short paper about your subjective

attitude toward an informant. Think about whether you've felt tentative or hesitant

toward your informant, feelings that you may not want to write about in your final paper

but that you acknowledge and understand as part of your researcher self. Use the followM

ing list to guide you:

1.

Describe your first meeting with your informant. What did you notice about yourself

as you began the interview process?

2.

Describe any gender, class, race, or age differences that may have affected the way

you approached your informant.

3.

Discuss ways you tried either to acknowledge or to erase these differences and the

extent to which you were successful.

4.

Discuss how your rapport changed over time in talking with and understanding your

informant and her worldview.

1113!!0i"®'~'111

Paul Russ faced many race and class differences when he interviewed his informants

about how they lived with AIDS. The most obvious was health, since his informants were

facing disease and he was not. Paul's response describes the many conflicting feelings he

had when he interviewed Jessie:

I picked up Jessie to drive him to the Health Project office for the interview. At first,

we didn't conduct the interviews at his house. I'm not sure if he was uncomfortable

about me seeing the inside of his house, if he didn't want the neighbors seeing a tall

white guy carrying a bunch of camera equipment into his house. Anyway, as Jessie

rode in my car, I was incredibly aware of the two different worlds we came from. I

had a bad case of white man's guilt. As he sat in my car, I apologized for the dog hair

left from taking my two dogs to the vet. He said that it was fine, that he was used to it.

Then he mentioned his dog, Princess. It was the first thing we had to talk about. Jessie admitted that he had little family support to cope with AIDS and that Princess was

his family. I shared that my dog had had a difficult pregnancy and that I almost lost

her. That's when he first opened up to me about his fear of living without Princess or

Princess living without him. When it later came up in our interview, it was an obvious

opportunity to encourage Jessie to speak personally.

229

Box21

continued

It was essential to establish common ground with him because I felt I had nothing in common with Jessie. Perhaps this was because he did not come from where

I came from and, perhaps, because he did not look like me. And while I've never

considered myself prejudiced, I realize that we all have prejudices deeply buried

inside no matter how intelligent or informed we are. In order to know him with some

degree of intimacy, I had to be vulnerable and share myself. I had to address the

baggage of race, class, education. I did this with all the informants in my project, and

it scared me because being friends with someone who is facing mortality requires an

emotional investment. I knew I had to establish a friendship.

While I was making a personal connection with Jessie, I also had professional

distance. With everything that came out of Jessie's mouth, I was thinking about how

it could be used in the final project. For me, interviewing is very active. It's not passive at all. You have to listen for meaning and listen for what's not being said. I had

trouble getting Jessie to speak from the heart. His responses to early questions were

pressed. I knew that if I were writing his story for a reader, l could project a much

clearer sense of his identity than he gave me on camera. I knew that. But I wasn't

writing his story. My mission was to record him telling his story in his own words.

So I looked for opportunities to help him reveal himself to me. Princess was one of

these opportunities.

Recording and Transcribing

Interviews provide the bones of any fieldwork project. You need your informants'

actual words to support your findings. Without informants' voices, you have no

perspective to share except your own. When you record and transcribe your

interviews, you bring to life the language of the people whose culture you study.

The process of recording and transcribing interviews has been advanced by

computers, software, and audio recorders that are small, relatively inexpensive,

and easily available. It's no coincidence that interviewing and collecting oral histories have become more :Popular in recent years \Vi th these accessible technologies. With a counting feature to keep track of slices of conversation and a pause

button to slow down the transcription process, even the most basic recorder

becomes a valuable tool for the interviewer.

Your choice of recording device will partially depend on whether you need

a recorder that is lightweight and handheld, high resolution, and low noise, or

one that records to a memory card. You may find that an inexpensive recorder

will suit your purposes just fine if you want to record one-on-one in a quiet space

and transcribe it yourself before integrating the interview into your own text.

However, if you plan to record in a noisy setting and make both the audio and

written transcription available, you will need a higher-quality recording device.

230

Recording and Transcribing

How you are going to share your work is another consideration. Will you

transcribe it into print only, or will you also distribute it as an audio file, podcast, or part of a multimedia presentation? How you will use your interview

material will affect what kind of equipment you purchase or rent.

Advances in recording devices and software have cut down the tedium of

sorting, classifying, and organizing huge amounts of data. But transcribing is

tedious business nonetheless. Three or more hours might be required to transcribe one hour of recording. And editing your audio files (if you choose to do

that) will require even more time. However, you learn an enormous amount

about your informants and yourself as you listen, replay, and select the sections

for your study.

You don't want to record everything you hear, nor do you want to transcribe it all. That's why it's important to prepare ahead-with research, guiding questions, and adequate equipment as well as knowledge of how to use it.

The following guidelines will help make your recording and transcribing go

smoothly.

1!"

Prepare your equipment Dead batteries and full memory cards can

ruin your data collection. Always can)' extras. Test your recorder before

using it by stating your name, the date, the place of the interview, and the

full name of your informant, and then playing this information back to

yourself. If you use a microphone, check out its range before you begin.

Most fieldworkers have stories of losing interviews because of equipment

malfunction. Be prepared.

)

r

y

"

Plan to take notes Consider how you will take fieldnotes during the

interview so that you'll capture all the features of the experience and have

a backup in case your recording equipment fails. You want to note the

environment where the interview takes place, the facial and body language

of your informant's responses, and any hesitations or interruptions that

take place. Your fieldnotes will help supplement the actual recording. Also

consider taking photos that you can use later to jog your memory.

;;~

Organize your i11terview time Be considerate in setting up a time and

place for the interview. Ask your informant what's convenient for him or

her. Arrive a few minutes early and test your equipment as well as the space

so that you don't have any extraneous noise or distractions. Remember to

have a timepiece-be it a watch or a phone-so that you can keep track of

interview time.

e

r

:I

r

r

e

t.

:I

Obtain your equipment Before borrowing or purchasing quality

equipment, research what's available. A digital counter that helps keep

track of time, multidirectional microphones that minimize ambient noise,

and functions that record separate tracks are some key features that will

facilitate your research. Investigate what's available and appropriate to

your research.

231

232

Chapter 5

Researching People: The Collaborative Listener

Organize time to listen to your audio

Begin the labeling process as

soon as possible. Key the filename (date, place, and informant's name)

into your audio device or download the file from your memory card

and label it on your computer. Also write down the filename of each

recording in your fieldnotes. After the intervie\.v, listen to the recording

as soon as you can to keep it fresh in your inind. Take notes as you

listen for topics covered, the1nes that emerge, and possible follow-up

questions.

Transcribe the interview As soon as you can, begin to transcribe

your recording. Don't wait too long, as the initial listening process

enhances your memory of the interview and your sense of purpose

about the project. Remember that you do not need to transcribe all the

material you record-only the sections that arc useful to your study.

To transcribe, listen directly fron1 the recorder or upload your audio

files to your computer. Check with your media lab to see if they have a

device sometin1es known as a footswitch. If they do, you can attach it to

your audio device to stop and start the recording as needed. This can be

immensely helpful. Whatever sections you decide to use, transcribe them

word for word using parentheses or brackets to indicate pauses, laughing,

interruptions, sections you want to leave out, or unintelligible words. For

example: [Regina laughs nervously] or [phone rang, maybe match? Or

march?-check with Regina] or [unintelligible word].

Bring yoi1r infonnant's la11guage to life As a transcriber, you must

bring your informant's speech to life as accurately and appropriately as

you can. Most researchers agree that a person's grammar should remain

as spoken. If an informant says, "I done," for example, it's not appropriate

to alter it to "I did." But if when you share the transcript with your

informant she chooses to alter it, respect those changes. As well,

many characteristics of oral language have no equivalents in print.

For more on using insider

language in your writing,

It is too difficult for either transcriber or reader to attempt to

see Chapter 6, page 2a-1.

capture dialect in written form. "Pahk the cah in Hahvahd Yahd"

is a respelling of a Boston accent, meant to show how it sounds.

But to a reader who's never heard it~even to an insider Bostonian who

isn't conscious of her acc~nt-the written version of her oral dialect

looks artificial and complicates the reading process. Anthropologists and

folklorists have long debated how to record oral language and currently

discourage the use of spelling as a \vay to approxhnate oral language.

Share your transcript Offer the transcripts to your infor1nant to read

for accuracy, but realize that you won't get many takers. Most informants

would rather wait for your finished, edited version of the interview. In any

case, the informant needs the opportunity to read what you've written. In

some instances, the informant may make corrections or ask for deletions.

But most of the time, the written interview becomes a kind of gift in

exchange for the time spent interviewing.

Recording and Transcribing

Edit the audio files

You may decide to go beyond the written transcript

to include your raw audio recording in a Web~based media presentation

that will add an extra dimension to your project. To create a usable

audio clip, you will need to use software to edit or splice your recordings

together. Talk to fellow students or researchers about what they use. If

possible, test-drive the editing software in order to understand its full

capacities before you purchase it.

You'll also want to consider what medium in which to share your audio

clips, as this will affect their length and content. Biogs, multimedia presentations, and podcasts are some of the popular formats at the time of this writing.

Be sure to include the URL for your blog, Web site, or podcast in your written

work-especially if you plan to publish it-so that your readers can access it

and enhance their understanding of your study.

:· .............................. "

.................. ., '.' ....................................................... ' ...:

Reminders for Recording and Transcribing

Set up your interview.

Familiarize yourself with your recording device.

:0

Arrive early and evaluate your recording environment.

Conduct the interview and take notes.

.

"P

Arrange sufficient time for listening to and transcribing the interview.

('!

Consider your final presentation format and its audience.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 00 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ,

............................................ .

.

Fieldworkers must turn interview transcripts into writing, n1aking a kind

of verbal film. As interesting as interview transcripts are to the researcher,

they are only partial representations of the actual interview process. Folklorist

Elliott Oring observes, "Lives are not transcriptions of events. They are artful

and enduring symbolic constitutions which demand our engagement and

identification. They are to be perceived and understood as wholes" (258). To

bring an informant's life to the page, you must use a transcript within your own

text, son1etimes describing the setting, the informant's physical appearances,

particular mannerisms, and language patterns and intonations. The transcript

by itself has little meaning until you bring it to life.

Cindie Marshall conducted a semeste1,long field project at Ralph's Sports

Bar, freq11ented by 1nen and \vomen who ride motorcycles and describe themselves as bikers. In "Ralph's Sports Bar," she combines her skills as a listener,

an interviewer, and n1ost of all a writer. In her study, her informants speak in

their O\vn voices, but Cindie contextualizes them, offering readers a look into

the biker subculture as it exists at Ralph's. As you read Cindie's research study,

notice the fieldworking skills she brings together.

233

234

Chapter 5

Researching People: The Collaborative Listener

Ralph's Sports Bar

Cindie Marshall

The Arrival

Everyone in the bar eyed me suspiciously during my visit. I didn't dress, walk,

or talk like the other women. Because of the illegal activity that goes on in the

bar, I guessed they were probably wondering if l was an undercover cop. I

realized that given the way the groups marked their boundaries, they probably

wouldn't be very inviting to a stranger asking a lot of questions about their

11

culture."

I decided that I would go to the table out front and perhaps there I could

find someone to answer my questions. At the very least, I could get some

fresh air and think about my approach. When I arrived at the table, there was

a woman sitting alone, drinking a beer. She had obviously had a lot to drink.

But we talked for a minute, and she was really quite nice. I introduced myself,

and she said her name was Teardrop. It was dark outside, so I couldn't see her

very well. We talked about the weather, and that led her to tell me that she had

moved here from Michigan three years ago and that she came to Ralph's

every day.

Ralph's Sports Bar

Recording and Transcribing

I knew that this was my opportunity to talk to a patron. On a long shot, I asked

her if she would like to shoot a game of pool. She agreed, and I was delighted. This

was an opportunity to ask questions and be seen with a regular.

Once we were inside, I saw that Teardrop was wearing new Lee jeans, a nice

pale yellow sweater, and a heart-shaped brooch. Her hair was brown but was

showing signs of graying. She had it neatly pulled back, and her bangs were teased

and carefully sprayed in place. It wasn't until she laughed that I noticed she was

missing her front teeth, both top and bottom. She had a small dark-green vine tattoo around her wrist. Most of the tattoo was covered by her watch.

As we played pool, I noticed she also had a black tattoo in the shape of a teardrop high on her cheek. When I asked her about her teardrop tattoo, she started

really talking to me. She told me that when she was 13, she had been kidnapped

by a group of bikers. The biker that kidnapped her had eventually sold her to a

fellow biker. This went on for years until finally, three years ago, she got away. The

teardrop was there because she couldn't cry anymore.

After hearing Teardrop's story, my admiration for the bikers' "do your own

thing" attitude was lost. She had described sheer abuse, and she wore that abuse

both on her face, in the shape of a teardrop, and in her smile, which was darkened

by missing teeth.

I left the bar to reflect on all that I had seen. I wanted to know why the groups

in the bar would come together in a place just to keep themselves segregated. The

only way I could get the answers to my questions was to talk to a person who had

been in all three groups and had spent a lot of time at the bar: Alice.

Conversation with Alice

Alice's boyfriend, Ralph, owned the bar. She had worked there prior to becoming

the receptionist at the law firm at which I worked, and she could probably tell me

everything I wanted to know.

Alice agreed to my interview, and I prepared a list of the three groups,

outlining what I thought their characteristics were. Alice read my list and we

began.

Characteristics of the "Rednecks"

We both agreed that one of the groups we would call "rednecks" for lack of a

better term. My list ascribed the following characteristics to this group: they

would be lazy; they would value freedom; they would not like or adhere to any

rules imposed on them; they would have no self-pride, either in their work or

appearance; they would demean women; they vvould have no materialistic values;

they would have no work ethic; and they would have no moral code among

themselves-it would be every man for himself.

After reviewing my list, Alice commented that actually, "they are hardworkR

ing and take pride in their jobs. Because they like to be able to say 'I do something

well.' ... Most of them are blueRcollar workers-construction workers, electricians,

235

236

Chapter 5

Researching People: The Collaborative Listener

Ralph's Sports Bar parking lot

people who do things with their hands. They're good at what they do to a certain

extent. A lot of them do change jobs frequently because of the drinking problem

that they have, and I think the majority of them do have drinking problems ....

They are lazy in the sense that they don't aspire to be anything more than what

they are."

We discussed how they treated their women, and Alice was quick to point out

"that's the biggest thing that they do .... It makes them feel like they are bigger."

We had talked prior to the interview about how uncomfortable I was at this bar. It

seemed that all the men treated the women with little or no respect.

On the subject of the rednecks' commitment to their fellow rednecks, I felt

that it would be every man for himself. I doubted that the rednecks had lasting

bonds or would stand up for a buddy in trouble. Alice said that she had "seen

where one night two guys would sit there and be buddy-buddy and would fight

together side by side. Two weeks later, they would fight each other."

Overall, the only real corrections Alice made to my list of characteristics was

that she strongly disagreed with my idea that rednecks were lazy. I asked her later

outside the interview how they could all be working yet spending their entire day

at Ralph's. She told me those individuals worked third shift and would simply go to

work drunk.

Characteristics of the Bikers

I had made a similar list of characteristics for the bikers at Ralph's. I had decided

that they, too, would value freedom and not like rules imposed on them. However,

they would have a higher moral code among themselves. I guessed that they didn't

care what other people thought of them and therefore would not be materialistic.

They would likely believe in making their own way and have a higher work ethic

than the rednecks. I would categorize them as more the "weekend warrior" type. I

also concluded that unlike the rednecks, they were probably ritualistic in the way

T

I

Recording and Transcribing

they meticulously parked their bikes. As for their treatment of women, after talking

with Teardrop, my view on that was clear. To the bikers, women were property, and

that was all.

Alice started her revision of my list by first telling me that 11 th ere are even

two different classes of bikers .... There are some bikers that are construction

workers, moochers, lowlifes. They live from day to day in how they get their

money, how they live. They come from a culture of brotherhood and "my buddy."

They are more clannish in that, if a guy drives a bike, they will stand beside

him no matter what. But also, there are a lot of bikers that come in there that

are white~collar workers; they do this on the weekend and like to be someone

different. They change their persona and how people perceive them. They put

on their leather pants and leather jackets and ride these motorcycles all weekend long and go back to their jobs. There are four or five of them that nobody

knows .... They are businessmen who own companies over in High Point ... but

you would never guess it by the way they look when they are sitting there on the

weekends drinking."

When we talked about the stereotypical biker, I asked her if she felt they

"treat women the same way the rednecks do." She said no. It was more of a kind

of ownership. She said, "'My old lady' and 'my old man,' this is the way they talk.

Rednecks are a little more respectful .. .'this is my wife' or 'this is my girlfriend: I

think that the 1old lady' and 1old man' can change from week to week. I have seen

[bikers] swap women around as if they were pieces of property." Surprisingly

enough, she made her point about the way bikers treat women by telling me

Teardrop's story.

We talked about the bikers and how they felt about freedom. Alice pointed

out, "You will find that most of the bikers will be outside, they will not be inside

the bar.... Bikers like the openness and the freedom -that's why they're bikers."

Conclusion

Alice is a reliable source of information on all three groups because she has been

very deeply connected to all of them. She truly does cross the line of the cultural

boundaries. As she put it, 11 l1ve been there. I've been a drinker and down on my

luck and slept in my car. I've been just where they are on many occasions ...."

My own stereotypes show in my list.of characteristics that I mapped out for

Alice to review. As for Alice, it is clear that she has stereotyped these groups, too.

After talking with her and visiting the bar, my question still remained: Why

would these distinctly different groups of people, each representing a unique

culture, come to one small bar, each mapping their turf and intentionally stayw

ing separated? Alice felt that the common bond was Ralph. Ralph moved easily

between the cultures and was actually a part of each group. She said that he did it

much the same as she did, the difference being that Ralph held the role of "leader"

or "policer" of each group. It was because of Ralph that the groups could all drink

their beer in harmony while at the bar.

I feel that it goes much deeper than that. The one common bond that all of

these groups share is love of freedom. The whitewcollar, partwtime biker enjoys the

237

238

Chapter 5

Researching People: The Collaborative Listener

freedom of wearing his leather and riding his Harley on the weekend without

anyone knowing. The redneck enjoys the freedom to drink his beer and be totally

wild if he wishes. All these people go to Ralph's to escape, to be free of

Read Cindie Marshall's full

the

watchful eyes of a judgmental society. They like the comfort of not

essay at bedfordstmartins

.com/fieldworking, under

worrying what anyone else will think because they know no one will

Student Essays.

care ....

Commentary: With More Time , , ,

I would love to have had more time to visit this bar and try to become part of

this culture. I am certain that there are errors in my list of characteristics, and I

know that these characteristics do not apply to every individual. It would have

been interesting to make connections in the bar and test my ideas; to prove

or disprove the stereotypes that I have about each group. With that research

perhaps it would be more clear where the stereotypes actually come from. I have

asked myself that question over and over again while writing this paper. At this

point, I cannot clearly say where they come from. I think it is a combination of

many sources.

I am still very intrigued with the biker culture. I wish I could have talked with

more female bikers to get their ideas on the treatment-of-women issue. Teardrop

really changed my attitude.

• • • • • o 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ' 1 0 > 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 • • • ; o o o o 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 , , q o o 0 0 0 0 0 0 0000;00•<>0000~000~••0000000000•00000

Before we discuss Cindie Marshall's study, we want to show you some

excerpts from her portfolio that illustrate her notetaking and categorizing skills.

In some of her interviews, she simply took notes and later checked them with

Alice. But she also recorded other conversations with Alice.

As she learned more from her interviews with Alice, Cindie looked carefully

at the words in the interview and began to see the patterns in the biker culture

that Alice described. Here is a sample from her recorded interview.

Cindie Marshall's Interview Notes

INTERVIEW WITH ALICE

C: Let's go over the category list. You believe the rednecks value their freedom

and are hardworking.

A: I think that they are hardworking and take pride in their jobs. Because they

like to be able to say, "!do something well." But their whole goal in what I

have viewed is that "I work to drink and I drink to work."

C: What kind of work do they do normally?

A: Most of them are blue-collar workers-construction workers, electricians,

people who do things with their hands. They're good at what they do to

a certain extent. A lot of them do change jobs frequently because of the

Recording and Transcribing

ly

I

drinking problem that they have, and I think the majority of them do have

drinking problems.

C: We talked about their being lazy, and we concluded that they're lazy in the

sense that they don't aspire to be anything more than what they are.

A: Yes. If their daddy taught them how to do construction or to build houses,

they don't make goals other than that.

C: And no self-pride in terms of their appearance?

A: Yes.

C: And we talked about how they demean women.

A: Yes, very much so. That's the biggest thing that they do. It makes them feel

stronger and feel like better people. It makes them feel like they are bigger.

ve

}

me

C: We talked about every man for himself, and you were saying that there were

no lasting bonds between the members of this particular culture within

the bar.

A: This is true. Because I have seen where one night two guys would sit there

and be buddy-buddy and would fight together side by side. Two weeks later,

they would fight each other. If the situation changes. The alcohol changes

people's personalities, and it varies day to day who is buddy-buddy.

C: The other culture that I saw when I was there is-you have your rednecks

and you have your bikers. What is the difference between the bikers and the

rednecks?

lls.

ith

A: I think that there are even two different classes of bikers.

illy

Jre

A: In this bar. In the sense that there are some bikers that are construction

workers, moochers, lowlifes. They live from day to day in how they get

their money, how they live. They come from a culture of brotherhood and

"my buddy." They are more clannish in that, if a guy drives a bike, they will

stand beside him no matter what. But also, there are a lot of bikers that

come in there that are white-collar workers; they do this on the weekend

and like to be someone different. They change their persona and how people

perceive them. They put on their leather pants and leather jackets and ride

these motorcycles all weekend long and go back to their jobs. There are four

or five of them that nobody knows. They are very honest and they tell you

what they do, that they are businessmen who own companies over in High

Point and one thing and another. But you would never guess it by the way

they look when they are sitting there on the weekends drinking. (Need to

ask her how these guys are treated by the full-time bikers. Do they tell the

full-time bikers about their other identity?)

m

ey

I

C: In this bar?

C: So those particular guys really fit both in among the bikers and the whitecollar professionals.

239

240

Chapter 5

Researching People: The Collaborative Listener

A: Yes.

C: So they are just choosing what culture they want to be in on weekends

basically. They could go into the biker thing or the professional white-collar

worker thing if they wanted to, just whichever way they wanted to go.

A: Yeah.

One of the strengths of Cindie's study is that she acquires different perspectives about Ralph's Sports Bar, which mirror the three categories of patrons she

is attempting to understand. Cindie positions herself at the outset as part of the

"white-collar weekend professional" group, admitting her own stereotypes. The

second perspective is what Cindie calls the "regular bikers," and her informant

Teardrop has belonged to that "regular hiker" culture much of her life. The third

perspective comes from Alice, Cindie's colleague at the law firm and Ralph's girlfriend, who defends the "redneck" position.

Cindie was fortunate to find Teardrop, who was in many ways an ideal informant. Teardrop frequents Ralph's every day, so she is an insider to the culture.

But Teardrop had stepped out of the biker culture long enough to be able to

reflect on it Teardrop was also an ideal informant because Cindie interacted

with her informally, gathering data as they shot pool together. Cindie didn't

record Teardrop's story but remembered it and wrote it into her ficldnotes. She

didn't worry about forgetting Teardrop's story because it was indelible, just like

the tattoo that was there "because she couldn't cry anymore." Cindie learned

this story from Teardrop as they interacted, each gaining trust for the other. Had

Cindie pulled out her tape recorder and tried to interview Teardrop by asking,

"So tell me how you got your name?" she probably wouldn't have heard Teardrop's story. The process of interaction and rapport allowed Cindie to acquire

good insider data.

Cindie's interview with Alice was entirely different because it was stn1ctured and planned. Cindie prepared a list of questions based on her own fieldnote observations of the three categories of patrons at the bar. Because Alice

was already a friend from the law firm where Cindie worked, she didn't need to

establish rapport.

Both Teardrop's and Alice's perspectives give weight and evidence to Cindie's own field observations, allowing her to confirm and disconfirm her data. As

we point out throughout this book, when researchers use multiple data sources

(interviews, fieldnotes, artifacts, and library or archival documents), they triangulate their findings. In this semester-long study, Cindie collected and analyzed varied sources (interviews, fieldnotes, and artifacts), and wrote from the

perspective of a won1an who intervievved other women about a predominantly

male subculture.

Because Cindie's final account is smoothly written and her research skills

are well integrated, it might not be apparent that she has engaged in many

Recording and Transcribing

aspects of the fieldworking process. A summary of her many fieldworking strate·

gies reveals, however, that Cindie was able to do all of the following:

r

Prepare for the field.

She gained access through her colleague Alice, an insider at Ralph's.

She read other research studies and material about fieldworking.

She drafted a research proposal that explained her interest in the biker

C·

subculture.

1e

1e

1e

She wrote about her assumptions and uncovered her prejudices about

bikers and rednecks.

:>

0

nt

:d

·1.

Use the researcher's tools.

She established rapport by hanging out at Ralph's and by locating

Teardrop, an insider informant.

She observed, taking detailed fieldnotes about the physical environment.

She participated in the culture by shooting pool with Teardrop, talking and

interacting at the same time.

She gathered descriptions of many cultural artifacts, taking photos and

noting what they implied.

She interviewed two informants, Alice (formally) and Teardrop

(informally), taking fieldnotes on their physical characteristics as well as

their stories.

g,

.rre

C·

:1.

:e

to

rr-

\s

'5

·i-

a·

1e

She transcribed Alice's interview, selecting potential sections to use in her

final project.

Interpret the fieldwork .

She read her data, proposal, fieldnotes, interview notes, and transcripts,

looking for themes and patterns.

She categorized her data into findings according to the three groups she

observed.

She made meaning co1laboratively with her informants:

With Alice, she verified her categories and disconfirmed her own

cultural stereotypes in her interview.

With Teardrop, she reflected on her data, particularly after her

interview, and expanded her findings with insights about the treatment

of women within the biking culture.

She reflected on how her data described a subculture.

ly

Present the findings.

She acknowledged and wrote about her position as an outsider.

ls

1y

She used descriptive details in her writing, selecting particular written

artifacts that convey the meaning of the culture.

241

Researching People: The Collaborative Listener

Chapter 5

242

She turned her informants into characters by melding her fieldnotes and

her transcripts.

She integrated her informants' voices with her narrative by using direct

quotations from her transcripts.

She designed sections with subheadings to guide her reader through

the project: "The Arrival," "Conversation with Alice," "Characteristics of

the 'Rednecks'," "Characteristics of the Bikers," "Conclusion," and her

commentary called "With More Time .... "

Analyzing Your Interviewing Skills

Reviewing and analyzing an excerpt from your transcripts can help you refine your interviewing skills and see ways to improve them. Pausing to look closely at your interviewing

and transcribing techniques may smooth the way for the rest of your project.

Select and transcribe a short section (no more than a page) from a key interview to share.

Play the corresponding portion of the recording as your colleagues read the transcript

and listen. Have your colleagues jot down notes and suggestions about your interview so

that you can discuss their observations together afterward:

1P

Has the interviewer established rapport with the informant?

0

Who talks more, the informant or the interviewer? Does that seem to work?

Bi

What was the best question the interviewer asked? Why?

©

What question might have extended to another question? Why?

e

How did the interviewer encourage the informant to be specific?

@

Were any of the questions closed?

Try using the line-by-line analysis in a small section, like the following example from

Cindie Marshall.

Here we analyze one of Cindie's transcripts, a portion of her interview with Alice. In

this excerpt, both interviewer and informant struggle with what they mean by the word

redneck and its associated cultural stereotypes. Fieldworkers need to be sensitive

to words that have different meanings for insiders in a culture. From her outsider

perspective, Cindie knew that the word redneck is a loaded term and that it's used

differently in different areas of the country. She was eager for Alice to help her clarify

what it meant to different groups at Ralph's Sports Bar.

C:

You believe the rednecks value their freedom and are hardworking.

(Cindie wants confirmation from Alice about one group of people she has observed

A:

frequenting Ralph's Sports Bar. She tries to get Alice to untangle her own perspective about

this category of patrons in the bar.)

I think that they are hardworking and take pride in their jobs. Because they like to be

able to say, "I do something well." But their whole goal in what I have viewed is that"!

work to drink and I drink to work."

C:

What kind of work do they do normally?

(Cindie follows Alice's lead, asking for more information, trying to find out more about

what they each mean when they use the term redneck. When the researcher recognizes

that one word has different meanings among different informants, she ought to try to

understand it.)

A:

Most of them are blue-collar workers-construction workers, electricians, people

who do things with their hands. They're good at what they do to a certain extent. A

lot of them do change jobs frequently because of the drinking problems that they

have, and I think the majority of them do have drinking problems.

C:

We talked about their being lazy, and we concluded that they're lazy in the sense that

they don't aspire to be anything more than what they are.

(Rather than trying to get more information from Alice about biker patrons who "do things

with their hands," Cindie introduces her own stereotype-that bikers are lazy, an idea that

she and Alice had discussed before. Cindie's question represents her indecision about

whether her stereotypes of bikers were true or if they came from movies.)

A:

Yes. If their daddy taught them how to do construction or to build houses, they don't

make goals other than that.

(Alice tried to move the conversation away from yet another stereotype-that bikers are

lazy-by offering her own observation: that bikers see1n to have limited career goals. Both

interviewer and informant struggle to understand each other's stereotypes.)

C:

And no self-pride in terms of their appearance?

(This is a leading question and in the end a closed question. Alice has no choice but to

answer yes or no. Later in the itlterview, Cindie asks a descriptive question that prompts

Alice to talk about what bikers actually do like to wear.)

A:

Yes.

C:

And we talked about how they demean women.

(Cindie raises yet another topic based on earlier conversations with Alice and also

based on stereotypes of bikers that, in her later interview with Teardrop, prove to be

true.)

A:

Yes, very much so. That's the biggest thing that they do. It makes them feel stronger

and feel like better people. It makes them feel like they are bigger.

243

246

Chapter 5

Researching People: The Collaborative Listener

them and talking to them, while they were killed. She was very distressed at their

deaths-"1 wept and wept:'

She had just finished the story when we arrived at her home-a small twostory town house, some distance from the campus. Downstairs was comfortable,

with the usual amenities-a sofa, armchairs, a television, pictures on the wall-

but I had the sense that it was rarely used. There was an immense sepia print of

her grandfather's farm in Grandin, North Dakota, in 1880; her other grandfather,

she told me, had invented the automatic pilot for planes. These two were the

progenitors, she feels, of her

agricultural and engineering

talents. Upstairs was her study,

with her typewriter (but no word

processor), absolutely bursting

with manuscripts and booksbooks everywhere, spilling out

of the study into every room

in the house. (My own little

11

house was once described as a

machine for working," and I had

a somewhat similar impression

ofTemple's.) On one wall was

a large cowhide with a huge

collection of identity badges

and caps, from the hundreds of

conferences she has lectured

at. I was amused to see, side by

Temple Grandin, Ph.D., a gifted animal scientist

side, an l.D. from the American

Meat Institute and one from the

American Psychiatric Association. Temple has published more than a hundred

papers, divided between those on animal behavior and facilities management

and those on autism. The intimate blending of the two was epitomized by the

medley of badges side by side.

Finally, without diffidence or embarrassment (emotions unknown to her), Temple showed me her bedroom, a:·n austere room with whitewashed walls and a single

bed and, next to the bed, a very large, strange-looking object. "What is that?" I asked.

"That's my squeeze machine," Temple replied. "Some people call it my hug

machine."

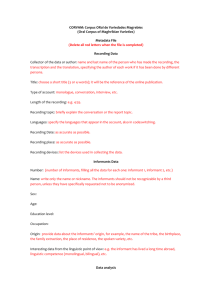

The device had two heavy, slanting wooden sides, perhaps four by three

feet each, pleasantly upholstered with a thick, soft padding. They were joined by

hinges to a long, narrow bottom board to create a V-shaped, body-sized trough.

There was a complex control box at one end, with heavy-duty tubes leading off to

11

another device, in a closet. Temple showed me this as well. lt's an industrial compressor," she said, "the kind they use for filling tires."

"And what does this do?"

The Informant's Perspective: An Anthropologist on Mars

247

"It exerts a firm but comfortable pressure on the body, from the shoulders to

the knees/' Temple said. "Either a steady pressure or a variable one or a pulsating

one, as you wish," she added. "You crawl into it-1 1 11 show you-and turn the compressor on 1 and you have all the controls in your hand, here, right in front of you.11

When I asked her why one should seek to submit oneself to such pressure,

she told me. When she was a little girl, she said, she had longed to be hugged but

had at the same time been terrified of all contact. When she was hugged, especially by a favorite (but vast) aunt, she

felt overwhelmed, overcome

Pl VWOOD CUTTING DIAGRAM: f'v.KE ALL curs ON CENTER

USE TWO SHEETS Of 3/4~ (19mm) AC

USE THIS LAYOlff so

by sensation; she had a sense of

PLYWOOD GRAIN WILL FACE INTHE RIGHT DIRECTION

peacefulness and pleasure, but

also of terror and engulfment. She

started to have daydreams-she

was just five at the time-of a magic

Pl!LlE MJUNT

machine that could squeeze her

-~OARD

powerfully but gently, in a huglike

way, and in a way entirely commanded and controlled by her.

Years later, as an adolescent, she had

seen a picture of a squeeze chute

designed to hold or restrain calves

and realized that that was it: a little

modification to make it suitable for

human use, and it could be her magic

machine. She had considered other

devices-inflatable suits, which

could exert an even pressure all over

the body-but the squeeze chute, in

its simplicity, was quite irresistible.

Being of a practical turn of mind,

Schematic diagram of Temple Grandi n's squeeze machine

she soon made her fantasy come

true. The early models were crude,

with some snags and glitches, but she eventually evolved a totally comfortable,

predictable system, capable of administering a "hug" with whatever parameters

she desired. Her squeeze machine had worked exactly as she hoped, yielding the

very sense of calmness and pleasure she had dreamed of since childhood. She

could not have gone through the stormy days of college without her squeeze

machine, she said. She could not turn to human beings for solace and comfort,

but she could always turn to it. The machine, which she neither exhibited nor concealed but kept openly in her room at college, excited derision and suspicion and

was seen by psychiatrists as a "regression" or "fixation" -something that needed

to be psychoanalyzed and resolved. With her characteristic stubbornness, tenacity,

single-mindedness, and bravery-along with a complete absence of inhibition or

hesitation-Temple ignored all these comments and reactions and determined to

find a scientific validation of her feelings.

11

11

[:

-::',;

248

Chapter 5

Researching People: The Collaborative Listener

Both before and after writing her doctoral thesis, she made a systematic

investigation of the effects of deep pressure in autistic people, college students,

and animals, and recently a paper of hers on this was published in the Journal

of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. Today, her squeeze machine,

variously modified, is receiving extensive clinical trials. She has also become the

world's foremost designer of squeeze chutes for cattle and has published, in the

meat-industry and veterinary literature, many articles on the theory and practice of

humane restraint and gentle holding.

While telling me this, Temple knelt down, then eased herself, facedown and

at full length, into the "V," turned on the compressor (it took a minute for the

master cylinder to fill), and twisted the controls. The sides converged, clasping