Towards a better understanding of supply chain quality

advertisement

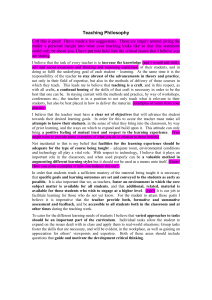

International Journal of Production Research Vol. 49, No. 8, 15 April 2011, 2285–2300 Towards a better understanding of supply chain quality management practices S. Thomas Foster Jra*, Cynthia Wallina and Jeffrey Ogdenb a Department of Business Management, Marriott School of Management, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT 84602, USA; bAFIT/ENS, Air Force Institute of Technology, 2950 Hobson Way, Wright Patterson AFB, OH 45433-7765, USA (Received 4 November 2009; final version received 25 February 2010) This paper reports the results of a comparative study of quality tools and methods adoption by operations and supply chain managers. A survey was administered to both types of managers in the Western United States. Performing a Kruskal Wallis analysis, we found support for the hypothesis that operations and supply chain managers approach quality management differently. We found that operations managers tend to manage supply chains through procedural methods such as ISO 9000 and supplier evaluation. Supply chain managers tend to be more collaborative, emphasising supplier development and complaint resolution. We found that both types of managers adopted on the job training, data analysis, supply chain management, customer relationship management, project management and surveys. This paper represents another step in defining the field of supply chain quality management. Keywords: supply chain quality management (SCQM); supply chain management; operations management; quality management; quality control 1. Introduction With the growth of the field of supply chain management, a great deal of effort has gone into defining and creating the related field of supply chain quality management (SCQM) (Flynn et al. 1994, Choi and Eboch 1998, Kuei et al. 2001, Spekman et al. 2002, Flynn and Flynn 2005, Foster 2008, Kaynak and Hartley 2008). SCQM has been defined as: ‘. . . a systems-based approach to performance improvement that leverages opportunities created by upstream and downstream linkages with suppliers and customers’ (Foster 2008). As evidence of the importance of this new field, the International Journal of Production Research, the Journal of Operations Management, and the Quality Management Journal have all recently published special issues in SCQM. This call for research is reflective of the degree to which both academics and managers in the field of operations management have become much more cognisant of supply chain management research and practice. This has resulted in an externalisation of the traditionally internalised operations view by focusing more attention on upstream and downstream linkages. *Corresponding author. Email: tom_foster@byu.edu ISSN 0020–7543 print/ISSN 1366–588X online ß 2011 Taylor & Francis DOI: 10.1080/00207541003733791 http://www.informaworld.com 2286 S.T. Foster Jr et al. Operations management has traditionally been explained by some version of an ‘inputs – transformation process – outputs’ view of the productive capability of the firm. From a quality perspective, operations managers have focused on internal activities such as process control, process improvement, product design improvement, and design of experiments. As a result, most six sigma improvement projects have focused on internal processes and cost reduction (Linderman 2008). Of course, the importance of suppliers and customers has long been emphasised by quality experts. This is found in Deming’s (1986) point about purchasing and not focusing on cost alone. We term the change of focus from an internal process orientation to one that emphasises linkages with upstream and downstream firms ‘externalisation’. Our theory is that as managers become more externalised, they will tend to adopt methods that are more holistic in nature – capturing not only internal processes but upstream and downstream processes and dynamics. With the emphasis on supply chain management, the roles of inter-firm and customer linkages have been elevated (Fawcett et al. 2006). This increased emphasis on linkages may have implications for how quality management is practised and what is emphasised by quality managers. In this paper, we explore the differences between quality management practices of operations managers and supply chain managers, including what quality tools are emphasised by each type of manager. The term ‘tool’ is used broadly for this study. ‘Tool’ can mean a method such as benchmarking, an approach to improving quality such as process improvement (PIT) teams, or a managerial concept such as leadership. While SCQM is still in the definitional stage, rigorous studies of SCQM practices and tools have yet to emerge. It is expected that this study will provide direction for researchers and instructors of quality management who wish to emphasise supply chain management. 2. Literature review and hypothesis development Supply chain management has developed as a field from the integration of operations and marketing management (Flynn and Flynn 2005). As a result, linkages with upstream firms – which was once the domain of purchasing – has been elevated in importance. The quality management precedence for this is found in Deming’s fourth point, ‘End the practice of awarding business on the basis of price tag alone. Instead, minimize total cost. Move towards a single supplier for any one item, on a long-term relationship of loyalty and trust’. This has resulted in a merging of quality management and supply chain management principles. Those who handle purchasing and logistics functions have gained a more quality-minded approach, and operations managers have increased their external focus on customer satisfaction (Foster and Ogden 2008). However, more work is needed as this merger is still far from complete and quality practices must advance even further from a traditional firm-centric and product-based mindset to an inter-organisational supply chain orientation involving customers, suppliers, and other partners (Robinson and Malhotra 2005). Miller (2002) stated that one of the key issues needing exploration was how supply chain management integrates with other operational performance initiatives such as lean manufacturing, quality management, and new product development. With the advent of SCQM, there appears to be support for the notion that integrating quality and supply chain management and their supporting functional areas is important to the success of organisations (Gustin 2001, Narasimhan and Das 2001, Hutchins 2002, Pagell 2004). Given that operational integration is often cited as being a prerequisite for International Journal of Production Research 2287 externalisation, quality management can serve as a strong base upon which to implement supply chain management practices. Supply chain management practices can result in operational benefits such as decreased production lead times, reduced costs, faster product development, and increased quality (Davis 1993, Billington 1994). It can also play a role in the success of quality management initiatives (Carter and Narasimhan 1994). In an early article about SCQM, Levy et al. (1995) discussed ‘total quality supply chain management’ and associated integration issues and Kuei et al. (2001) pointed out that organisational performance can be enhanced through improved SCQM. Trent and Moncza (1999) examined how purchasing and sourcing activities contributed to total quality and concluded that purchasing and supply chain managers can positively affect supplier quality. Firms with more successful TQM (Total Quality Management) programmes were more likely than firms with less successful TQM programmes to stress formal performance evaluations of purchasing employees, involve purchasing employees in key decision-making processes, support purchasing employees who took risks, provide more TQM training to purchasing employees, and reward purchasing employees for individual goal attainment (Carter and Narasimhan 1994). While SCQM can provide benefits, it is not easily accomplished. The structure and culture of an organisation, reward systems, and the amount or lack of communication across functions have been identified as factors that inhibit or promote integration within the organisation (Pagell 2004). In an article calling for the integration of quality and supply chain management, Theodorakioglu et al. (2006) found a significant positive correlation between supplier management practices and total quality management practices. Quality has always been one of the most important performance criteria, even with a conventional purchasing strategy. Dickson (1966) showed that the ability to meet quality is one of the three most critical determinants in choosing suppliers. Choi and Hartley (1996) found that a construct they labelled the ‘consistency factor’ (which includes conformance quality, consistent delivery, quality philosophy, and prompt response) to be the most important supply selection criterion in the supply chain. Bessant (1990) pointed out that buyer-supplier relationships that were once based on price have shifted to a number of non-price factors, with quality in first position. Many buyer-supplier relationships have evolved into partnerships at the stage of product design and development. Bevan (1987) pointed out that as these supplier relationships evolved, the role and definition of quality changed, and thus we see the attention that supply chain management quality is receiving in the literature. Foster and Ogden (2008) showed that supply chain managers tended to emphasise quality tools and quality values more than traditional operations managers. This research builds on that work to examine specific patterns of quality tool adoption and emphasis. There is an old adage that, ‘Our actions demonstrate who we are’. This can be said for operations and supply chain managers. By understanding how they differ in quality tool adoption, we can better understand SCQM. Hence, the following hypothesis: H1.Supply chain managers and operations managers will utilise quality practices and tools differently. The primary focus of this research is to aid in the understanding of the domain of SCQM by exploring both the use of quality tools in practice and the diversity of approaches. What tools and methods are emphasised as we move to more of a supply chain focus? Just as importantly, what practices will not be emphasised as much? 2288 S.T. Foster Jr et al. 2.1 Tools Prior studies have discussed particular tools relating to supply chain quality (Sila et al. 2006). In a preliminary phase of this study, we asked a group of 20 graduate students in quality management to create an affinity diagram of the 57 tools listed in this study. Whilst the tools and approaches found in this study are not all-inclusive, they do represent a wide variety of approaches utilised in industry. The resultant affinity diagram with categories is shown in Table 1. While this categorisation of tools is informative, it is not intended to be a rigorous study of tools classifications as that is not the purpose of this paper. We only use this tools categorisation scheme in this paper to aid in efficiently organising this literature review as we will briefly define these tools. Process oriented tools are primarily focused on improving the efficiency and quality of production methods. Benchmarking is one such tool. Camp (1994) argues that benchmarking is most useful in the context of process. This allows companies to compare processes and to chart courses for improvement. Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems are focused on managing production processes and information throughout the firm (Ptak and Schragenheim 2003). JIT (just-in-time) and lean are approaches that focus on improving process efficiency and resource usage (Wedgwood 2007). Quality awards can be used to reward outstanding process management and performance (Hendricks and Singhal 2001). Six sigma black belts use DMAIC to work on improving process Table 1. Quality tools included in the study. Process Tools Basic Tools Statistical Tools Benchmarking ERP Focused Factory JIT Lean Awards Six Sigma Failsafing DMAIC Data Analysis Project Mgt. Surveys PIT Teams Costs of Quality PERT 7 Basic Tools 7 Managerial Tools 5-S Control Charts Computer-aided Testing (CAT) Computer-aided Inspection Gage R&R Supply Chain Tools Design Tools Management Tools Supply Chain Management Customer Relationship Management Complaint Resolution Supplier Development Environmental Design Design Teams QFD CAD Supplier Evaluation Customer Benefits Package Single Sourcing ISO 9000 SERVQUAL Leadership On the job Training Change Management Human Resources Management Concurrent Design Systems Thinking Prototyping Contingency Theory Quality Assurance Design Deming FMEA Quality Circles DOE PDCA Design for Manufacture Crosby Reliability Indexes Malcolm Baldrige Award Robust Design Juran DMADV Hoshin Planning International Journal of Production Research 2289 performance and cost (Linderman 2008). Failsafing or poka yoke involves trying to improve products and processes so that they cannot fail. Our basic tools classification is somewhat expansive. The basic seven tools of quality include well-known tools such as flowcharts and Ishikawa charts (Ishikawa 1985), and advanced managerial tools such as affinity diagrams that are used for handling more subjective data in managerial decision making (Brassard 1989). 5-S is a Japanese approach to standardising and cleaning to improve layouts and orderliness of operations (Foster 2010). Program evaluation and review technique (PERT) is a tool used in managing projects (Kerzner 2005). Data analysis involves gathering, testing, and performing analysis on data (Evans and Lindsay 2007). Quality control professionals are very familiar with statistical tools such as control charts, computer-aided testing (CAT) and inspection, and Gage R&R. Control charts are used in monitoring process stability from sampled data (Grant and Leavenworth 1996). Computer-aided testing is used to check that component parts, sub-assemblies, and full systems are within specified tolerances and also perform up to specification (Meredith 1987). Computer-aided inspection is used in examining products for defects during or after the production process (Meredith 1987). Gauge repeatability and reproducibility (Gage R&R) is used to ensure that measurements are accurate. The supply chain tools and approaches are focused on upstream and downstream interactions. Supply chain management is defined as involving process management and project management to meet customers’ needs collaboratively (Fawcett et al. 2006). Customer relationship management is an approach to creating value through long-term interactions with customers (Foster 2010). Complaint resolution is a closed-loop process for gathering, resolving, and utilising customer complaints for improvement (Evans and Lindsay 2007). Supplier development involves sharing knowledge with customers to improve their quality and service to the customer (Kaynak and Hartley 2008). Supplier evaluation is the process of grading and registering suppliers at times using standards such as ISO 9000 (Sroufe and Curkovic 2008). The customer benefits package is a tool for identifying those services that will be provided to customers (Collier 1994). Single sourcing is a process for reducing the numbers of suppliers for a particular item to one (Lee and Ansari 1985). Design tools are primarily approaches to improving products in order to satisfy customers. Environmental or green design is focused on reducing negative impacts of products and processes (Foster et al. 2000). Quality function deployment (QFD) or ‘house of quality’ is an approach to design that aids in communication between engineers and marketers (Hauser and Clausing 1988). Computer-aided design (CAD) utilises systems to aid in the design process (Meredith 1987). Concurrent design uses design teams to reduce the time required to generate new product designs (Nevins and Whitney 1989). Quality assurance design is a concept that states that quality is only guaranteed through efficacious design processes. Failure modes and effects analysis (FMEA) is used by teams of engineers to identify potential flaws in design so that designs can be improved during the design phase (AIAG 2008). Design of experiment (DOE) involves performing off-line experiments to ensure that inputs to products and processes are configured correctly to optimise customer satisfaction with products and services (Foster 2010). Design for manufacture (DFM) is an approach to design pioneered by Ford Motor Company to help to improve the ease of manufacture for products (AIAG 2008). Reliability indexes are used to determine the extent to which products meet design specifications (Kececioglu 1993). DMADV is a six sigma process proposed by Motorola design engineers for improving 2290 S.T. Foster Jr et al. products (Wedgwood 2007). Robust design is a Taguchi (Taguchi et al. 1989) concept that results in products that will maximise benefit to society. Management tools are concepts, tools, and approaches used in directing efforts to satisfy customers. Leadership is included in this research as the literature is unanimous that effective leadership is necessary in managing quality (Foster 2010). On the job training was proposed by Deming (1986) as necessary to create a culture conducive to quality production. Change management involves a variety of approaches to directing the implementation of new ideas and approaches to performing tasks (Evans and Lindsay 2007). Human resources management (HRM) is the process of directing people to benefit the organisation (Cardy et al. 2000). Systems thinking was suggested by Deming (1986) as a way to view processes holistically to understand how components of a system interact to create customer value. Contingency theory proposes that not all firms are the same therefore managers need to adapt to make positive change given their particular organisational context and competitive environment (Foster 2006). Plan-do-check-act (PDCA) was the cycle proposed by Shewhart (1980) as a generalised process for making organisational improvement. Crosby (1979) proposed an approach to managing quality that was primarily behavioural and was encapsulated in his steps for improvement. The Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award (MBNQA) is a process by which outstanding firms are identified and rewarded for quality performance (NIST 2009). Juran (1988) proposed a trilogy for improvement that included planning, control, and improvement. Hoshin planning is an annualised strategic process that aligns quality improvement efforts with strategic objectives (Witcher and Butterworth 1999). Again, this listing of methods is not intended to be all-inclusive. However, these tools are a broad collection of approaches to improving quality that will provide insights to the differences between how operations and supply chain managers approach quality improvement. 2.2 Diverse approaches The theory motivating this research is borrowed from anthropology and has been applied in other fields such as information systems (Olson and Ives 1981). Theory relating to diversity states that individuals from differing social systems and structures may process information and solve problems differently potentially adding to the richness of solutions (Cox and Blake 1991, Reagans and Zuckerman 2001, Canas and Sondack 2008). In systems science, research has been performed examining differences between users and analysts (Olson and Ives 1981). Earlier research studies examined the differences between scientists and generalists. Since operations management grew out of the scientific orientation the field was originally dominated by engineers and mathematical modellers. As an example of this phenomenon, empirical research has only recently been widely accepted in operations circles (Swamidass 1991). On the other hand, supply chain has grown out of the fields of marketing and logistics (Fawcett et al. 2006). From a research perspective, this field has been characterised as having a longer tradition of empirical work and more emphasis on collaboration and cooperation (Fawcett et al. 2006). Since these diverse management traditions exist, it is expected that operations and supply chain managers will approach the solution of quality problems differently. However, there is very little research examining difference in practices between operations and supply chain managers (Foster and Ogden 2008). It is expected that this research will help to address this gap. International Journal of Production Research 2291 3. Methods Data for this study was gathered by inviting participants to complete a web-based survey. The survey included seven-point Likert scales that allowed respondents to rank the extent to which they utilised various quality tools or approaches to their work. The items were drawn from the most commonly applied tools in quality management and tools that were selected from the SCQM literature. The tools were drawn from two most widely adopted textbooks in quality management (Evans and Lindsay 2007, Foster 2010) as well as iSixSigma and FreeQuality, two leading tools-oriented websites. These lists of tools were submitted to a panel of six supply chain and quality managers to externally validate their inclusion in the survey. As a result, one tool was removed from the survey and two were added. Not all survey items were used in the analysis for this paper. While the listing of tools for this research is not all inclusive – there are literally hundreds of tools in the literature – we completed a list of 57 tools that is representative of major areas of quality including process tools, basic tools, statistical tools, supply chain tools, design tools, and management tools. We utilised seven-point Likert scales (strongly disagree, disagree, moderately disagree, neutral, moderately agree, agree, strongly agree) that allowed respondents to rank the extent to which their companies utilised the various tools. The instrument was pretested with an MBA class (n ¼ 30) in one of the authors’ universities and with 12 members of a western United States Chapter of APICS, The Association for Operations Management (hereafter referred to as APICS) chapter. Chronbach’s alpha was computed with alpha 4 0.95 for all of the items, providing evidence of internal content validity. Comments were received from the initial respondents. While some minor adjustments were made to the form of the survey, no items were added or deleted as a result of the pretest. While the MBA responses were not used in any further analysis beyond the pretest, the APICS member responses were included in the final results. The population for the survey initially included professional members of APICS and the Institute of Supply Management (ISM). The respondents were from chapters from two states in the US Intermountain West region. To increase the number of supply chain respondents, the survey was also administered to members of a Western Round Table of the Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals (CSCMP). As will be seen, there were differences in how the survey was administered within each organisation, largely because each chapter’s leadership wanted to protect its members from unwanted contact. The survey was administered according to the Dillman (1999) method for administering web-based surveys. The board of directors for the local APICS chapter provided members’ e-mail addresses to the researchers. An e-mail was sent to 82 members of the chapter, explaining the purpose of the survey and inviting the members to respond to the survey. We emphasised that by responding to the survey, the APICS members would be providing important service for the state university. We also promised to share a summary of the responses with the chapter members. Two weeks after the first e-mail, a follow-up e-mail was sent to the members. Of the 82 potential respondents, 44 responded to the survey. While persons who are active in these professional organisations tend to emphasise professional development and are receiving training through their organisations, it was not necessary that they be familiar with all tools in the survey. They will be more familiar with those tools utilised in their jobs. Other tools would either be unrated or rated lowly as they were not utilised by the respondent. 2292 S.T. Foster Jr et al. The ISM chapter would only allow us to circulate a sign-up list for those who would volunteer to respond to the survey at an ISM monthly chapter meeting. After the volunteers provided their e-mail addresses to the researchers, the e-mail was sent to the ISM members, asking them to participate in the survey. Two weeks after the mailing, a follow-up was sent. Of 41 members who initially signed up to participate in the survey, 33 responded. To increase the number of responses, we contacted the CSCMP western roundtable and were allowed to attend a day-long seminar. The leadership of the CSCMP requested that we administer the survey on paper the day of the seminar to avoid e-mailing their members. To encourage participation, we included survey respondents in a drawing for a $50 Amazon.com gift certificate. Of the 44 people attending the conference, 25 participants filled out the paper survey. While the survey was administered at the beginning of the day, the gift certificate was awarded at the end of the day to provide ample time to thoughtfully complete the survey. Combining the three groups, we totalled 102 respondents (though surveys from two of these were discarded as unusable) out of 167 potential respondents, for a 60% response rate. The high response rate was the result of working closely with the chapters to maximise the success of our research efforts. This approach was also very time consuming and required good relations and trust with the local chapters as their members receive many web-based surveys, and board members can be criticised for allowing members to receive unwanted solicitations to complete surveys. To enable the comparison of quality practices based on a given perspective, the survey respondents were asked to identify their jobs as primarily operations management oriented or primarily supply chain management oriented. The organisations we selected for this study are relevant to the study of differences in perceptions between operations and supply chain managers. APICS identifies itself as the ‘global leader and premier source of the body of knowledge in operations management’. Ninety-six percent (p 5 0.0001) of those who identified themselves as APICS members identified their job responsibilities as primarily operations management. ISM was formerly named the National Association of Purchasing Managers and identifies itself as ‘the largest supply management association in the world as well as one of the most respected’. CSCMP was known as the Council of Logistics Management (CLM) from 1985 to 2004 and identifies itself as ‘the preeminent worldwide professional association of supply chain management professionals’. Our correlation analysis found that 94% (p 5 0.0001) of the ISM and CSCMP members identified themselves as primarily supply chain management professionals. The responses of the two groups were compared in our analysis. It should be noted that the two sample groups were mutually exclusive in that no particular respondent responded to the survey more than once. 4. Results Using SAS, we examined differences in the utilisation of quality tools between operations managers and supply chain managers. For each quality tool, the items were worded in this manner: ‘Within the context of your organization, the following quality tools are utilized’. The respondent then rated each tool on a separate seven-point scale. The summary means of these items are contained in Table 2. We computed and found the differences between mean responses for operations and supply chain managers. A positive difference indicates that a particular tool is utilised to a 2293 International Journal of Production Research Table 2. Mean scores and differences for tools. SC tools On the job training Data analysis Supply chain management Customer relationship management Leadership Benchmarking Project management Surveys Complaint resolution Supplier development Change management ERP Human resources management Focused factory Supplier evaluation Design teams Process improvement teams QFD JIT Customer benefits package Lean CAD Control charts Systems thinking Costs of quality Awards Design for the environment Contingency theory Computer-aided testing (CAT) Concurrent design Prototyping Single sourcing ISO 9000 Computer aided inspection Quality assurance through design FMEA Six sigma Deming DOE Failsafing PERT Design for manufacture Quality circles 7 basic tools Reliability indexes 7 managerial tools PDCA Gage R&R Robust design DMAIC Crosby SC scores Ops scores Diff. 5.65 5.57 5.54 5.44 5.44 5.30 5.21 5.19 5.09 5.00 4.93 4.91 4.91 4.86 4.86 4.82 4.71 4.71 4.64 4.58 4.53 4.52 4.48 4.48 4.33 4.27 4.22 4.19 4.18 4.16 4.16 4.16 4.14 4.11 4.11 4.09 4.07 4.05 4.02 4.00 3.96 3.96 3.93 3.92 3.87 3.83 3.82 3.76 3.75 3.75 3.69 4.79 5.02 4.93 4.95 4.56 4.49 4.95 4.84 4.26 4.38 4.14 4.21 4.60 3.86 4.74 4.88 4.40 4.83 4.44 4.02 4.42 4.91 4.17 4.02 3.88 3.69 3.53 3.84 4.40 3.91 4.74 3.79 4.84 4.12 3.62 3.93 3.53 3.47 3.57 3.65 3.76 3.98 3.83 3.81 3.48 3.51 3.91 3.84 3.81 3.51 3.02 0.86 0.55 0.61 0.49 0.88 0.82 0.26 0.36 0.83 0.62 0.79 0.70 0.30 1.00 0.11 0.06 0.31 0.12 0.19 0.56 0.11 0.39 0.32 0.46 0.45 0.58 0.68 0.36 0.21 0.26 0.57 0.37 0.69 0.01 0.49 0.16 0.54 0.59 0.45 0.35 0.20 0.01 0.10 0.12 0.40 0.32 0.09 0.08 0.06 0.23 0.67 (continued ) 2294 S.T. Foster Jr et al. Table 2. Continued. SC tools DMADV 5-S MBNQA SERVQUAL Juran Hoshin SC scores Ops scores Diff. 3.64 3.63 3.51 3.42 3.39 3.36 3.17 3.76 2.81 3.05 3.09 3.37 0.47 0.13 0.70 0.37 0.30 0.01 Note: *Kruskal Wallis statistic (K) ¼ 6.12; df ¼ 1; p 5 0.025. greater extent by supply chain managers than by operations managers. Conversely, a negative response means that operations managers tended to emphasise a particular tool more than supply chain managers. To test our hypothesis, we then ranked the quality tool means and performed a Kruskal Wallis test to analyse differences in ranks where the treatment was type of manager. Kruskal Wallis is perhaps the most widely used non-parametric technique for testing whether different samples have been drawn from the same population (Daniel 1990). Kruskal Wallis is often referred to as a one-way analysis of variance for ranks. The Kruskal Wallis test statistic is a weighted sum of squares of deviations of sums of ranks from the expected sum of ranks. The Kruskal Wallis test statistic is computed as: Pg ni ðri rÞ2 K ¼ ðN 1Þ Pg i¼1 2 , Pn i j¼1 rij r i¼1 where: ni is the number of observations in group i; rij is the rank (among all observations) of observation j from group i; N is the total number of observations across all groups; Pi ri ¼ ð nj¼1 rij Þ=ni ; and r ¼ ðN þ 1Þ=2 is the average of all the rij. As can be seen in Table 2, the Kruskal Wallis statistic of 6.12 was significant (p 5 0.025). This means that there was a significant difference in the mean rankings attributed to different tools when comparing operations and supply chain managers. Note that the Kruskal Wallis statistic pertains to the entire list of items, not just single items. Table 3 shows relative rankings of the means of the different tools for supply chain and quality managers. While the means for the supply chain managers tend to be higher than the operations managers’, the relative rankings of importance for the two groups are instructive. 5. Conclusions and discussion This paper represents another step in the process of understanding and more clearly defining of the field of supply chain quality management. Performing the Kruskal Wallis analysis, we found support for the hypothesis that operations and supply chain managers do approach quality management from differing perspectives. In the following paragraphs, we will discuss these differences. Figure 1 provides a summary of the differences and similarities for quality tool adoption between operations and supply chain managers. We developed this list by 2295 International Journal of Production Research Table 3. Tools rankings for operations and supply chain managers. SC tool On the job training Data analysis Supply chain management Customer relationship management Leadership Benchmarking Project management Surveys Complaint resolution Supplier development Change management ERP Human resources management Focused factory Supplier evaluation Design teams Process improvement teams QFD JIT Customer benefits package Lean CAD Control charts Systems thinking Costs of quality Awards Design for the environment Contingency theory Computer-aided testing (CAT) Concurrent design Prototyping Single sourcing ISO 9000 Computer aided inspection Quality assurance through design FMEA Six sigma Deming DOE Failsafing PERT Design for manufacture Quality circles 7 basic tools Reliability indexes 7 managerial tools PDCA Gage R&R Robust design DMAIC Crosby SC rank Ops rank Diff.* 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 10 1 4 2 14 15 3 8 21 20 24 22 13 33 11 6 18 9 16 26 17 5 23 27 32 42 47 35 19 31 12 39 7 25 44 29 46 51 45 43 40 28 36 38 50 49 30 34 37 48 56 9 1 1 2 9 9 4 0 12 10 13 10 0 19 4 10 1 9 3 6 4 17 0 3 7 16 21 7 10 1 19 7 26 9 10 7 10 14 7 4 1 14 7 6 6 4 17 14 12 1 5 (continued ) 2296 S.T. Foster Jr et al. Table 3. Continued. SC tool DMADV 5-S MBNQA SERVQUAL Juran Hoshin SC rank Ops rank Diff.* 52 53 54 55 56 57 53 41 57 55 54 52 1 13 3 0 2 5 Note: *Kruskal Wallis statistic (K) ¼ 6.12; df ¼ 1; p 5 0.025. Figure 1. Tool study findings. identifying tools that were in the top 10 for both operations and supply chain managers. The tools and approaches that scored highly for both supply chain and operations managers were on the job training, data analysis, supply chain management, project management and surveys. All of these approaches are widely applicable and are useful for managers and individuals who work in the day to day operations and supply chain worlds. To identify tools that were emphasised more by supply chain managers than operations managers, we identified tools that had a difference score less than or equal to 9. These tools and approaches included leadership, benchmarking, complaint resolution, supplier development, change management, ERP, focused factory, awards, design for the environment, six sigma, and Deming. International Journal of Production Research 2297 On the other hand, operations managers emphasised QFD, CAD, CAT, prototyping, ISO 9000, DFM, PDCA, Gage R&R, and the 5 S’s to a greater extent than supply chain managers. These are tools where the difference score for ranking was greater than or equal to 9. Reflection on the identified differences reveals that operations managers tend to manage supply chain relationship through procedural methods such as ISO 9000 and supplier evaluation. Supply chain managers tend to adopt more collaborative approaches such as supplier development, awards, and complaint resolution processes. As the field of operations moves more in a supply chain direction, this could change. Supply chain professionals have long emphasised collaboration and this has become part of the supply chain culture. Another difference between supply chain and operations managers is in the area of design. Excepting the environment, operations managers tend to emphasise product design to a much greater extent than supply chain managers. While the data does not reveal the reasons for this, this could be an interesting area for further study. The tools and approaches that were ranked low by both types of managers were DMAIC, Crosby, DMADV, MBNQA, SERVQUAL, Juran, and hoshin planning. These were tools and approaches that were ranked in the bottom 10 by both types of managers. There are a few surprises. While some of these approaches are somewhat limited in application, the low rankings for the Baldrige award and the six sigma methodologies were somewhat surprising. This could reflect the age of the Baldrige award process and the lack of general application in a wide variety of organisations. The low ranking for six sigma processes was more startling. While the data does not explain why the low rankings occurred, it could be that DMAIC and DMADV are more the domain of six sigma black belts. Since these black belts tend to be more specialised, operations and supply chain managers may not utilise these processes in daily problem solving and decision making. The findings from this research are instructive in helping to understand the domain of supply chain quality. From an academic perspective, we consider these results to be another step in defining SCQM by identifying the approaches and methods that are emphasised by managers in their attempt to improve the quality of products and services produced. As a relatively new field of study, more research is needed to create an operational definition for SCQM with a similar level of detail as exists in the operationsrelated quality literature. From a practitioner perspective, operations and supply managers would benefit from knowing what approaches and methods their counterparts are emphasising to determine what, if any, internal collaboration should be attempted. As noted above, internal alignment has been shown to be an antecedent to successful external alignment and improved supply chain performance. From a pedagogical perspective, those who teach supply chain quality management will now better understand what to emphasise so that supply chain students can be well prepared for the work they will be performing. Instead of focusing on more specialised approaches, such as six sigma, maybe students need more preparation in training methods, data analysis, developing relationships with customers, and so forth. Like all research, there are limitations in our study. The primary limitation of this research was the size and regional nature of the data collection sample. Future studies should be larger in number and involve greater geographical areas. Furthermore, since cultural differences are expected to be reflected in practices, future research is needed to explore quality approaches and methods in various cultures. Research of this nature would 2298 S.T. Foster Jr et al. also provide a basis for international comparative studies of quality practices. The other major limitation is temporal. This data reflects a single snapshot of practice. We suspect that tool adoption is evolutionary and that longitudinal studies may reveal changing patterns of tool adoption. References AIAG, 2008. Potential failure mode and effects analysis. Southfield, MI: Chrysler, Ford, and General Motors. Bessant, J., 1990. Managing advanced manufacturing technology – the challenge of the fifth wave. Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell. Bevan, J., 1987. What is co-makership? International Journal of Quality and Reliability Management, 4 (3), 47–57. Billington, C., 1994. Strategic supply chain management. OR/MS Today, 21 (2), 21–27. Brassard, M., 1989. The memory jogger plus. Metheun, MA: Goal QPC. Camp, R., 1994. Business process benchmarking. Milwaukee, WI: ASQ Press. Canas, K. and Sondak, H., 2008. Opportunities and challenges of workplace diversity. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Cardy, R., Gove, S., and DeMatteo, J., 2000. Dynamic and customer-oriented workplaces: implications for HRM practice and research. Journal of Quality Management, 5 (2), 159–186. Carter, J. and Narasimhan, R., 1994. The role of purchasing and materials management in total quality management and customer satisfaction. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 30 (3), 2–13. Choi, T. and Hartley, J., 1996. An exploration of supplier selection practices across the supply chain. Journal of Operations Management, 14 (4), 333–343. Choi, T. and Eboch, K., 1998. The TQM paradox: relations among TQM practices, plant performance, and customer satisfaction. Journal of Operations Management, 17 (1), 59–75. Collier, D., 1994. The service quality solution. Milwaukee, WI: ASQ Press. Cox, T. and Blake, S., 1991. Managing cultural diversity: implications for organizational competitiveness. Academy of Management Executive, 5 (3), 45–56. Crosby, P.B., 1979. Quality is free. New York: Mentor. Daniel, W.W., 1990. Applied nonparametric statistics. Boston, MA: PWS Kent. Davis, T., 1993. Effective supply chain management. Sloan Management Review, 34 (4), 35–46. Deming, W.E., 1986. Out of the crisis. Boston, MA: CAES. Dickson, G., 1966. An analysis of supplier selection systems and decisions. Journal of Purchasing, 2 (1), 5–17. Dillman, D., 1999. Mail and internet survey: the tailored method. New York: Wiley. Evans, J.L. and Lindsay, W., 2007. Managing for quality and performance excellence. Mason, OH: Thomson South-Western. Fawcett, S., Ellram, L., and Ogden, J., 2006. Supply chain management: form vision to implementation. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Flynn, B.B., Schroeder, R.G., and Sakaibara, S., 1994. A framework for quality research and an associated measurement instrument. Journal of Operations Management, 11 (4), 339–366. Flynn, B. and Flynn, E., 2005. Synergies between supply chain management and quality management: emerging implications. International Journal of Production Research, 43 (16), 3421–3436. Foster, S.T., Sampson, S.E., and Dunn, S., 2000. The impact of customer contact on environmental initiatives for service firms. International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 20 (2), 187–203. Foster, S.T., 2006. Process improvement: one size does not fit all. Quality Progress, 39 (7), 54–61. International Journal of Production Research 2299 Foster, S.T., 2008. Towards an understanding of supply chain quality management. Journal of Operations Management, 26, (4), 461–467. Foster, S.T. and Ogden, J., 2008. On difference in how operations and supply chain managers approach quality management. International Journal of Production Research, 46 (24), 6945–6963. Foster, S.T., 2010. Managing quality: integrating the supply chain. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Grant, E. and Leavenworth, R., 1996. Statistical quality control. New York: McGraw Hill. Gustin, C.M., 2001. Supply chain integration: reality or myth? Distribution Business Management Journal, 1 (1), 71–74. Hauser, J. and Clausing, D., 1988. The house of quality. Harvard Business Review, 66 (3), 63–73. Hendricks, K.B. and Singhal, V.R., 2001. The long-run stock price performance of firms with effective TQM programs as proxied by quality award winners. Management Science, 47 (3), 359–368. Hutchins, G., 2002. Supply chain management: a new opportunity. Quality Progress, 35 (4), 111–112. Ishikawa, K., 1985. Guide to quality control. White Plains, NY: Quality Resources. Juran, J., 1988. Juran on planning for quality. New York: Free Press. Kaynak, H. and Hartley, J., 2008. A replication and extension of quality management into the supply chain. Journal of Operations Management, 26 (4), 468–489. Kececioglu, D., 1993. Reliability and life testing handbook. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Kerzner, H., 2005. Project management: a systems approach to planning, scheduling, and controlling. New York: Wiley. Kuei, C., Madu, C., and Lin, C., 2001. The relationship between supply chain quality management practices and organizational performance. International Journal of Quality and Reliability, 18 (8–9), 864–873. Lee, S. and Ansari, A., 1985. Comparative analysis of Japanese just-in-time purchasing and traditional US purchasing systems. International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 5 (4), 5–14. Levy, P., et al., 1995. Developing integration through total quality supply chain management. Integrated Manufacturing Systems, 6 (3), 4–13. Linderman, K., 2008. Six sigma: definition and underlying theory. Journal of Operations Management, 26 (4), 536–554. Meredith, J., 1987. The strategic advantages of new manufacturing technologies for small firms. Strategic Management Journal, 8 (3), 249–258. Miller, C.R., 2002. Competing though supply chains: the rise of integrated supply chain management. Journal of the Reliability Analysis Center, 10 (3), 1–4. Narasimhan, R. and Das, A., 2001. The impact of purchasing integration and practices on manufacturing performance. Journal of Operations Management, 19 (5), 593–609. Nevins, J. and Whitney, D., 1989. Concurrent design of products and processes: a strategy for the next generation in manufacturing. New York: McGraw Hill. NIST, 2009. Malcolm Baldrige criteria for performance excellence. Gaithersburg, MD: NIST. Olson, M. and Ives, B., 1981. User involvement in system design: an empirical test of alternative approaches. Information and Management, 4 (4), 183–195. Pagell, M., 2004. Understanding the factors that enable and inhibit the integration of operations, purchasing and logistics. Journal of Operations Management, 22 (5), 459–487. Ptak, C. and Schragenheim, E., 2003. ERP: tools, techniques, and applications for integrating the supply chain. Boca Raton, FL: St. Lucie Press. Reagans, R. and Zuckerman, E., 2001. Networks, diversity, and productivity: the social capital of corporate R&D teams. Organization Science, 12 (4), 502–517. 2300 S.T. Foster Jr et al. Robinson, C. and Malhotra, M., 2005. Defining the concept of supply chain quality management and its relevance to academic and industrial practice. International Journal of Production Economics, 96 (3), 315–325. Shewhart, W., 1980. Economic control of quality of manufactured product. Milwaukee, WI: ASQ Press. Sila, I., Ebrahimapour, M., and Birkholz, C., 2006. Quality in supply chains: an empirical analysis. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 11 (6), 491–502. Spekman, R.E., Spear, J., and Kamauff, J., 2002. Supply chain competency: learning as a key component. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 7 (1), 41–55. Sroufe, R. and Curkovic, S., 2008. An examination of ISO 9000: 2000 and supply chain quality assurance. Journal of Operations Management, 26 (4), 503–520. Swamidass, P.M., 1991. Empirical science: new frontier in operations management research. Academy of Management Review, 16 (4), 793–812. Taguchi, G., Elsayed, E., and Hsiang, T., 1989. Quality engineering in production systems. New York: McGraw Hill. Theodorakioglu, Y., Gotzamani, K., and Tsiolvas, G., 2006. Supplier management and its relationship to buyers’ quality management. Supply Chain Management, 11 (2), 148–159. Trent, R. and Moncza, R., 1999. Achieving world-class supplier quality. Total Quality Management, 10 (6), 927–939. Wedgwood, I., 2007. Lean sigma. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Witcher, B. and Butterworth, R., 1999. Hoshin kanri: how Xerox manages. Long Range Planning, 32 (3), 323–332. Copyright of International Journal of Production Research is the property of Taylor & Francis Ltd and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.