Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders

advertisement

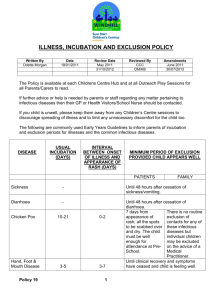

Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders http://ebx.sagepub.com/ Patterns and Predictors of Disciplinary Exclusion Over Time: An Analysis of the Seels National Data Set Lisa Bowman-Perrott, Michael R. Benz, Hsien-Yuan Hsu, Oi-man Kwok, Leigh Ann Eisterhold and Dalun Zhang Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders published online 13 October 2011 DOI: 10.1177/1063426611407501 The online version of this article can be found at: http://ebx.sagepub.com/content/early/2011/09/20/1063426611407501 Published by: Hammill Institute on Disabilities and http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders can be found at: Email Alerts: http://ebx.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://ebx.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav >> OnlineFirst Version of Record - Oct 13, 2011 What is This? Downloaded from ebx.sagepub.com by SAGE editorial on March 9, 2012 407501 an-Perrott et al.Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders © Hammill Institute on Disabilities 2010 EBXXXX10.1177/1063426611407501Bowm Reprints and permission: http://www. sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Patterns and Predictors of Disciplinary Exclusion Over Time: An Analysis of the SEELS National Data Set Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders XX(X) 1­–14 © Hammill Institute on Disabilities 2011 Reprints and permission: http://www. sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/1063426611407501 http://jebd.sagepub.com Lisa Bowman-Perrott1, Michael R. Benz1, Hsien-Yuan Hsu2, Oi-man Kwok1, Leigh Ann Eisterhold1, and Dalun Zhang1 Abstract Disciplinary exclusion practices are on the rise nationally, as are concerns about their disproportionate use and lack of effectiveness. This study used data from the Special Education Elementary Longitudinal Study to examine patterns and predictors of disciplinary exclusion over time. Students with emotional/behavioral disorders were most likely to be excluded and be excluded multiple times, followed by students with attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder and students with learning disabilities. For all student groups, being excluded in the first wave was a strong predictor of being excluded at later points in time. Student gender (male students) and ethnicity (African American students) were associated with a greater probability of exclusion over time. Students with higher social skills, as reported by teachers, had a lower probability of being excluded over time. Implications for practice, policy, and future research are discussed. Keywords disciplinary exclusion; emotional disturbance; disorders/disabilities; ADHD; learning disability; research/statistical methods Disciplinary exclusion measures such as suspension and expulsion are common responses to student misbehavior in school. While these practices are more often applied at the middle and high school levels, they have been observed and studied across both elementary and secondary school settings (Skiba & Sprague, 2008). In 2003, 11% of all K-12 students had been suspended from school (in- or out-ofschool), and 2% had been expelled (U.S. Department of Education, 2007a). Furthermore, according to the U.S. Department of Education (2007b), during the 2005-2006 school year 74% of all “serious” disciplinary consequences assigned were suspensions of 5 days or more; 5% were expulsions from school. While the practice of disciplinary exclusion has existed for decades (Grosenick et al., 1981), its use has increased, particularly with the introduction of zero tolerance policies in schools (Krezmien, Leone, & Achilles, 2006; Skiba & Sprague, 2008). This increased use has given rise to two major concerns. First, disciplinary exclusion measures have been applied disproportionately to students with disabilities (Krezmien et al., 2006). For example, students with emotional/behavioral disorders (EBD), learning disabilities (LD), and attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) experience higher rates of exclusion than their peers in other disability categories and students in general education (Achilles, McLaughlin, & Croninger, 2007; Wagner, Newman, & Cameto, 2004; Zhang, Katsiyannis, & Herbst, 2004). Specifically, Cooley (1995) found that students with disabilities (most of whom were identified as EBD or LD) were more than twice as likely as their peers without disabilities to be suspended or expelled. Students who are culturally and linguistically diverse (CLD)—namely, African American and Hispanic students (Gregory, Skiba, & Noguera, 2010; Rocque, 2010)—have been overrepresented as well. Second, disciplinary exclusion measures are not an effective strategy for problem behavior. That is, suspension and expulsion practices do not improve problem behavior or promote school safety (Skiba, 2000). In reality, these measures are associated with a number of undesirable consequences. Skiba, Peterson, and Williams (1997) found that most suspensions were linked with “disrespectful” and “disobedient” behaviors rather than violent behaviors. Skiba (2000) also reported that past suspensions can predict future ones; up to 40% of suspensions have been attributed to repeat offenses. Moreover, these practices have been 1 Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas, USA National Taiwan Normal University, Taipei, Taiwan 2 Corresponding Author: Lisa Bowman-Perrott, 4225 TAMU, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843-4225. Email: lbperrott@tamu.edu Downloaded from ebx.sagepub.com by SAGE editorial on March 9, 2012 2 Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders XX(X) associated with future adverse consequences, including school disengagement (Reschly & Christenson, 2006), academic failure (Brown, 2007), school dropout (Christle, Jolivette, & Nelson, 2005), homelessness (Whitbeck & Hoyt, 1999), running away from home (Tyler & Bersani, 2008), and involvement in the juvenile justice system (Leone et al., 2003). In 2007, Achilles et al. provided a cross-sectional examination of disciplinary exclusion using the Special Education Elementary Longitudinal Study (SEELS) national data set. Achilles et al. investigated sociocultural correlates of the likelihood of disciplinary exclusion among students with EBD, LD, and ADHD, students the authors identified as being at high risk of disciplinary exclusion. Among their recommendations for future research was a call for longitudinal research that examined disciplinary exclusion over time. To date, this knowledge base is limited to cross-sectional research with nationally representative samples that examines disciplinary exclusion at one point in time (Achilles et al., 2007), 1-year state-level studies (Rausch & Skiba, 2004; Skiba, Wu, Kohler, Chung, & Simmons, 2001; Sundius & Farneth, 2008), 1-year districtlevel studies (Raffaele Mendez & Knoff, 2003), and stateand district-level studies that have examined patterns of disciplinary exclusion over time (Arcia, 2007; Krezmien et al., 2006). No longitudinal research has been conducted that examines patterns and predictors of disciplinary exclusion over time with a nationally representative sample of students with disabilities. Thus, research is needed that (a) investigates the influence of early exclusion on later exclusion and (b) identifies variables associated with higher rates of exclusion over time (U.S. Department of Education, 2002). The purpose of the present study was to address this need by conducting a comprehensive examination of patterns of disciplinary exclusion over time and factors associated with higher rates of exclusion. The SEELS data set was used, drawing information on patterns and predictors from all three waves of data. Several variables have been identified as being associated with disciplinary exclusion that generally can be thought of as falling into the following categories: student demographic characteristics, family/household characteristics, student academic and social skills, and school characteristics. A discussion of each of the areas follows. Four student demographic variables have been identified consistently in the literature as being associated with disciplinary exclusion: disability, age, gender, and ethnicity. Disciplinary exclusion disproportionately affects students with disabilities. Of students with disabilities ages 6 to 17, 9% to 33% were suspended during the 2000-2001 school year (U.S. Department of Education, 2003). Among these, students with EBD, ADHD, and LD are most likely to be excluded (Achilles et al., 2007; U.S. Department of Education, 2007c). For students with and without disabilities, older students and males are more likely to be suspended and expelled (Blackorby et al., 2007; Skiba, 2000). Males are also more likely to be excluded at earlier grades and to lose more days of school instruction (Clark, Petras, Kellam, Ialongo, & Poduska, 2003). African American youth are suspended and expelled at rates greater than their peers from other ethnic groups (U.S. Department of Education, 2007a). Furthermore, African American students are also more likely to be given out-of-school versus in-school suspension as a disciplinary consequence (McFadden, Marsh, Price, & Hwang, 1992). Finally, findings from some studies have indicated that students’ ethnicity is significant even after controlling for socioeconomic status (SES; Skiba, Michael, Nardo, & Peterson, 2002). Previous research has identified several family/household characteristics as being associated with higher rates of disciplinary exclusion, including SES, family structure, student (family) mobility, and parent involvement and expectations. Achilles et al. (2007) found that students from lower SES families were at greater risk for exclusion than their peers from higher SES families. They also found that SES impacted the likelihood of exclusion more than students’ ethnicity when all variables were accounted for in their model. Similarly, in their study of elementary and middle school students, Blackorby et al. (2007) found that students from families with higher household incomes (more than $50,000) were involved in fewer disciplinary actions than students from families with household incomes below $20,000. Family structure can hinder or facilitate how parents influence the future outcomes of their children (Amato, 2001). In examining data from the National Health Interview Survey on Child Health, Dawson (1991) found that, in general, children under age 18 from “disrupted marriages” (whose mothers had been previously married or who lived with their mother and stepfather) or whose mothers never married were significantly more likely to be suspended or expelled. With respect to disability, Achilles et al. (2007) found that family structure was associated with the likelihood of being excluded for students with EBD. Student mobility, defined as students changing schools for reasons other than promotion to the next school level, has been shown to be related to behavior problems (Simpson & Fowler, 1994). In the Achilles et al. (2007) study, student mobility (multiple school changes) was associated with disciplinary exclusion for students with EBD. Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest a relationship between student disciplinary exclusion, parent expectations, and parent involvement in and satisfaction with his or her child’s school. Blackorby et al. (2007) found that high parent expectations were associated with fewer disciplinary actions for the students in their study, but this relationship did not retain significance when other factors (e.g., student demographics and family characteristics) Downloaded from ebx.sagepub.com by SAGE editorial on March 9, 2012 3 Bowman-Perrott et al. were considered. Findings of a relationship between parent involvement in school and student exclusion have been mixed. Christle, Nelson, and Jolivette (2004) found that low parental involvement was associated with higher rates of both suspension and expulsion. In contrast, Achilles et al. (2007) found no relationship between parent involvement and exclusion. However, in the Achilles et al. study, there was a relationship between parent satisfaction and disciplinary exclusion. Parents of students with EBD and LD who had been excluded reported less satisfaction with their child’s school. While much of the current literature has examined relationships between disciplinary exclusion practices and student demographic and family/household variables, a few studies have examined relationships between disciplinary exclusion and various discrete variables that generally could be considered as illustrative of student skills and school characteristics. Blackorby et al. (2007) found that students who were involved in fewer disciplinary incidents were reported by their parents to have high social skills and were reported by teachers to cooperate with peers, follow directions, and complete homework on time. In addition, there is some evidence to suggest that rates of disciplinary exclusion are higher in schools with a greater number of students living in poverty (Christle et al., 2005; Raffaele Mendez, Knoff, & Ferron, 2002) and in schools located in urban settings (Achilles et al., 2007). In summary, current research indicates that disciplinary exclusion practices are: (a) used with increasing frequency nationwide, (b) of questionable effectiveness, (c) associated with later adverse consequences, and (d) applied disproportionately among certain student groups. Students with EBD, LD, and ADHD are among students at high risk. A majority of the research that has examined correlates of disciplinary exclusion has focused on student demographic variables (e.g., gender and ethnicity) and family/household characteristics (e.g., SES), with relatively less attention given to other potentially important factors such as student skills and school characteristics. Some state-level research suggests that early disciplinary exclusion is a predictor of later exclusion. For these reasons, a comprehensive examination of the patterns of disciplinary exclusion over time is needed that includes an investigation of patterns of exclusion for highrisk students with disabilities and factors associated with higher rates of exclusion over time. Using the national, longitudinal SEELS data set, the current study was conducted to explore two research questions: (a) Are students who are excluded in Wave 1 more likely to be excluded in later waves (i.e., Wave 2 and Wave 3)? If yes, are there differences in the probability of exclusion for the three groups of students (EBD, ADHD, and LD) in later waves?; and (b) what are the effects of selected predictors on student exclusion status over time? Do predictors perform consistently to explain student exclusion status for students with EBD, ADHD, and LD? Method Participants and Procedures Participants and data for this study were drawn from the Special Education Elementary Longitudinal Study (SEELS), a nationwide study of the characteristics, experiences, and outcomes of elementary and middle school students with disabilities. Information on the study design is summarized here and provided in detail elsewhere (e.g., Wagner, Kutash, Duchnowski, & Epstein, 2005; Wagner, Marder, Blackorby, & Cardoso, 2002). SEELS was funded by the Office of Special Education Programs of the U.S. Department of Education and conducted by SRI International. SEELS data were collected in three waves between the 1999-2000 school year and the 2004-2005 school year on a nationally representative sample of students who were between ages 6 and 12 at the start of the study. Data were collected through parent interviews, teacher and school administrator questionnaires, and direct student assessments. Data were collected over a 6-year period with 1 to 2 years between waves. SEELS participants were selected through a two-stage sampling process to produce a nationally representative sample. In the first stage, a stratified (geographic region, size, wealth) random sample of 1,124 local education agencies (LEAs) was selected. A total of 245 LEAs and 32 special schools agreed to participate in the study and provided rosters of students receiving special education services. From these schools, a stratified (primary disability) random sample of 11,512 students was selected to participate in the study. Responses to the Wave 1 parent interview resulted in a final sample of 9,824 students (Wagner et al., 2002). The current study focused on three disability categories associated with high rates of suspension and expulsion (U.S. Department of Education, 2007c): LD, EBD, and ADHD. Primary disability roster information contained in the SEELS data set was used to select participants. Drawing on previous research (Achilles et al., 2007; Schnoes, Reid, Wagner, & Marder, 2006), roster information on ADHD was confirmed by parent report that a given student was identified as having ADHD. These procedures resulted in a final sample of 2,597 students (LD = 1,047; EBD = 874; ADHD = 676) (see Table 1). Measures Dependent variable: Student disciplinary exclusion. The dependent variable for both research questions was the number of student disciplinary exclusions. Two items were extracted from the SEELS parent interview data as Downloaded from ebx.sagepub.com by SAGE editorial on March 9, 2012 4 Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders XX(X) Table 1. Demographic Characteristics by Disability Group Characteristic Ethnicity Caucasian African American Hispanic Other Gender Male Female Age 6 to 9 10 to 12 13 to 14 Living in poverty Yes No Exclusion rate Wave 1 Wave 2 Wave 3 LD (n = 1,047) EBD (n = 874) 67.8% 16.1% 13.5% 2.7% 59.7% 27.5% 10.3% 2.5% 67.5% 32.5% 78.9% 21.1% 25.9% 61.0% 13.1% 32.0% 56.1% 11.9% 25.2% 74.8% 32.2% 67.8% 7.4% 10.6% 17.1% 30.3% 38.3% 37.8% ADHD (n = 676) 81.0% 11.9% 5.1% 2.0% 76.7% 23.3% 30.0% 58.4% 11.6% 14.2% 85.8% 15.7% 20.9% 18.1% Entries are percentages based on the n for each disability group. measures of exclusion. The first item asked parents to report whether their child had been suspended during the past school year (yes = 1, no = 0), and the second item asked parents whether their child had been expelled during the past school year (yes = 1, no = 0). Parents were asked to report on each item in each of the three waves of data collection. According to parent report, 17.14%, 22.32%, and 23.57% of students had been either suspended or expelled at Wave 1, Wave 2, and Wave 3, respectively. Predictor variables. To identify factors associated with exclusion, a two-step process was used. First, drawing upon the conceptual framework and previous data reports from the SEELS study and the literature reviewed earlier, items were extracted from the SEELS data set that were determined in previous research to be potentially related to higher rates of exclusion. Theoretically relevant items were selected from the Wave 1 parent interview data, teacher survey, and school characteristics survey. Selected items were grouped into four conceptual categories for analysis purposes: (a) student demographic characteristics, (b) family/household characteristics, (c) student academic and social skills, and (d) school characteristics. Second, univariate relationships among the predictor variables and between the predictor variables and the dependent variable were examined. This was done for the sample as a whole and separately for students with EBD, ADHD, and LD. Given the size of the sample, only variables with statistically significant correlations of .15 or higher (with the dependent variable) were retained for further consideration. Analyses were also conducted to check for potential outliers. No extreme outliers or non-normal variables potentially caused by any outliers were found (see Note 1). A discussion of the four factors follows. Student demographic characteristics. Four demographic variables were extracted from the SEELS database: disability, ethnicity, age, and gender. Only participants who had a primary disability of LD (40.32%), EBD (33.65%), or ADHD (26.03%) were selected for inclusion in the current study. “Ethnicity” included three major racial/ethnic groups: Caucasian (68.51%), African American (AA; 18.83%), and Hispanic (HIS; 10.23%). Other racial/ethnic groups (2.43%) were recoded as “other” due to the small number of members in those groups. Caucasian was used as the reference group based on previous research on the disproportionate use of exclusion policies with students from ethnically/linguistically diverse groups. Three dummy-coded variables were created to represent the three ethnic groups in the analyses. “Age” reported in the SEELS data set was also used and included ages 6 through 14 in the current study (M = 10.51, SD = 1.71). “Gender” of the student was used and included two levels, male (coded as 1; 73.71%) and female (coded as 0; 26.29%). Family/household characteristics. Seven theoretically relevant variables were examined to investigate the role of family/household characteristics on rates of exclusion over time: SES risk, family structure, mobility, parent expectations, parent involvement in school, parent report of child’s school experiences, and parent satisfaction with school. Three variables—parent involvement in school, parent Downloaded from ebx.sagepub.com by SAGE editorial on March 9, 2012 5 Bowman-Perrott et al. report of child’s school experiences, and parent satisfaction with school—were all fitted as latent variables. Examination of the univariate relationships revealed that two latent variables, child’s school experiences and parent satisfaction with school, were highly correlated (r = .81). To prevent the plausible multi-collinearity caused by these two highly correlated latent factors, only satisfaction with school was included in these analyses since parent satisfaction with school was of interest. “SES Risk” (Achilles et al., 2007) was a composite score including three indicators of socioeconomic disadvantage: (a) whether family income was below the poverty level (a variable in the SEELS data set that was coded “yes” or “no”; 24.19% of students in the sample came from families in poverty), (b) whether a member of the family utilized benefits from any of three federal benefit programs during the previous 2 years (Temporary Assistance to Needy Families, Food Stamp, and Supplemental Security Income; 27.76% of students were from families that participated in one or more of these programs), and (c) whether the education level of the head of household was less than high school (17.19% of students). Each SES risk indicator was scored yes = 1 or no = 0, resulting in an overall risk composite score of 0 to 3 (M = 0.65, SD = 0.89). That is, a student received a score of 3 on the SES risk composite variable if he or she lived in a family with an income below the poverty level, in which a family member participated in any of the three federal benefit programs, and in which the head of household had an education level less than high school. “Family Structure” was a binary variable describing whether a student lived in a two-parent household, no (coded 1, 36.86%) or yes (coded 0, 63.14%). “School Mobility” was a measure of the number of times a student changed schools since kindergarten, excluding changes due to promotion to the next grade level (M = 1.10, SD = 1.37). “Parent Expectations” was a measure of parents’ expectations that their child would graduate from high school with a regular diploma. Parent Expectations was scored on a scale of 1 (definitely won’t) to 4 (definitely will), with a score of 4 indicating the highest expectations for graduation from high school (M = 3.52, SD = 0.66). “Parent Involvement in School” was fitted as a latent variable and was made up of four items. For each item, parents were asked to rate how frequently they were involved at their child’s school in the past year. Frequency was measured by a scale of five choices: never (coded as 0), one to two times (coded as 1), three to four times (coded as 2), five to six times (coded as 3), and more than six times (coded as 4). Parents reported whether they (or another adult in the household) had: (a) attended a general school meeting (M = 1.66, SD = 1.20), (b) attended a school/class event (M = 1.51, SD = 1.30), (c) volunteered at their child’s school (M = 0.77, SD = 1.20), or (d) attended a parent/teacher conference other than an IEP (individualized education program) meeting (M = 1.60, SD = 1.09). “Satisfaction With School” was fitted as a latent variable that included six items. For each item, parents were asked to rate their level of satisfaction in the past year using a 4-point scale: very dissatisfied (coded as 1), somewhat dissatisfied (coded as 2), somewhat satisfied (coded as 3), and very satisfied (coded as 4). Parents rated their satisfaction with the following: (a) their child’s school (M = 3.18, SD = 0.92), (b) their child’s teacher (M = 3.37, SD = 0.86), (c) special education services (M = 3.32, SD = 0.89), (d) other education received (M = 3.32, SD = 0.78), (e) amount and difficulty of homework (M = 3.03, SD = 0.91), and (f) level of information they received from the school about their child’s behavior and academic performance (M = 3.37, SD = 0.91). Student academic and social skills. Three theoretically relevant variables were examined to investigate the role of academic skills on rates of exclusion over time: student academic achievement, extracurricular activities, and grade retention. “Academic Achievement” (M = 87.39, SD = 13.38) was a composite score computed by averaging two items (i.e., a standard score on math calculation and a reading passage comprehension score from the direct assessment data set) and could range from 25.5 to 121.0 for this sample. The average composite score mean for this sample was lower than that of the entire SEELS sample. “Extracurricular Activities” (M = 0.36, SD = 0.48) referred to student involvement in extracurricular activities and was scored yes = 1 and no = 0. “Grade Retention” (M = 0.27, SD = 0.44) was based on parent report of whether the child was ever held back a grade in school, which was scored yes = 1 and no = 0. Three theoretically relevant variables were also used to investigate the role of student social skills on rates of exclusion over time: peer interactions, teacher interactions, and social adjustment. “Peer Interactions” (M = 3.13, SD = 0.80) was based on the parent report of how well the student got along with peers; “Teacher Interactions” (M = 3.35, SD = 0.76) referred to how well students got along with teachers. For both variables, parent responses were based on their perceptions of student interactions in the previous year and were measured on a 4-point scale: not at all well (coded as 1), not very well (coded as 2), pretty well (coded as 3), and very well (coded as 4). The third variable, “Social Adjustment,” was an existing composite variable in the SEELS data set. It was fitted as a latent variable consisting of 11 items measuring teacher rating of the following student behaviors: (a) joins group activities without being told to (M = 2.25, SD = 0.65), (b) makes friends easily (M = 2.17, SD = 0.68), (c) starts conversations rather than waiting for others to talk first (M = 2.28, SD = 0.67), (d) acts impulsively (M = 1.87, SD = 0.76), (e) invites others to join in activities (M = 1.98, SD = 0.62), (f) fights with others (M = 2.32, SD = 0.66), (g) Downloaded from ebx.sagepub.com by SAGE editorial on March 9, 2012 6 Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders XX(X) controls his or her temper in conflict situations with other students (M = 2.26, SD = 0.67), (h) avoids situations that are likely to result in trouble (M = 2.18, SD = 0.62), (i) cooperates with peers without prompting (M = 2.29, SD = 0.56), (j) responds appropriately when pushed or hit by another student (M = 2.11, SD = 0.71), and (k) argues with others (M = 2.06, SD = 0.70). For each item, teachers rated the frequency with which these behaviors occurred in the previous year using a 3-point scale: never (coded as 1), sometimes (coded as 2), and very often (coded as 3). School characteristics. Three theoretically relevant variables were examined to investigate the role of school characteristics on student exclusion over time: urban school, school climate, and school risk. “Urban School” (M = 0.32, SD = 0.47) referred to whether the child’s school was in an urban location (yes = 1 and no = 0). “School Climate” (M = 3.45, SD = 0.67) referred to teacher ratings of whether the school climate was positive (a created variable in the SEELS data set comprised of teacher ratings of the quality of the school leadership and whether the school was a safe place for students). It was measured on a 4-point scale: strongly disagree (coded as 1), disagree (coded as 2), agree (coded as 3), and strongly agree (coded as 4). “School Risk” was fitted as a latent variable that included four items: (a) percentage of students eligible for the free or reduced-price lunch program (M = 2.08, SD = 1.05), (b) percentage of students enrolled who moved away from the school during the school year (M = 2.34, SD = 1.21), (c) total number of suspensions/expulsions for all students at the school in the last year (M = 2.49, SD = 1.12), and (d) percentage of enrolled students absent from school on a typical day (M = 2.32, SD = 1.13). Each item was recoded into four categories: less than 25% (coded as 1), 26% to 50% (coded as 2), 51% to 75% (coded as 3), and more than 75% (coded as 4). Data Analysis Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was used to analyze the data. SEM permits the simultaneous examination of numerous relations between predictor and dependent variables. In addition, it allows a model with both observed and latent variables to be estimated simultaneously. Mplus (Version 5.2; Muthén & Muthén, 2007) was adopted for all the analyses in this study. To account for the dependency among the observations (i.e., students nested within school districts), analyses were conducted using the “Type = Complex” feature in Mplus (Muthén & Muthén), which adopted the Huber-White correction for the standard errors of the parameter estimates. In addition, to analyze discrete/ categorical dependent variables, a maximum likelihood estimation with standard errors was used along with a chisquare test statistic—both of which are robust to non-normality and non-independence of observations (MLR) with logit link. Missing data were handled by using the “Type = missing” feature in Mplus, which adopted the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) approach to incorporate information from incomplete responses and retain all 2,597 participants in the analyses. Results are reported as odds ratios. An odds ratio of 1.0 indicates there is no relationship between a predictor and the outcome variable. The greater the departure from an odds ratio of 1.0, the greater the relationship between the two variables. For example, if Predictor X1 (e.g., gender; coded 1 = male, 0 = female) has an odds ratio of 2.0, then a participant in the study with X1 = 1 (a male student) is two times more likely to be excluded than a participant with X1 = 0 (a female student). Conversely, if the odds ratio of Predictor X2 is .50, then a participant with characteristic X2 is two times less likely to be excluded than a participant without characteristic X2. In this sense, the odds ratio serves as an easy-to-interpret description of the magnitude of the relationship between the predictor variable of interest and disciplinary exclusion. Results Probability of Exclusion Over Time Students who were excluded in the first wave were more likely to be excluded again in the second wave (i.e., odds ratios from Wave 1 to Wave 2 ranged from 2.45 to 8.29) (see Figure 1). Similarly, students who were excluded in Wave 2 were more likely to be excluded again in Wave 3, although the odds ratios from Wave 2 to Wave 3 were relatively smaller (range from 3.25 to 5.83) than those from Wave 1 to Wave 2. Finally, as Figure 1 depicts, exclusion status at Wave 1 predicted exclusion status at Wave 3 for students with LD and students with ADHD at conventional levels of significance (p < .05), but not for students who have EBD. For all three disability groups, students excluded in Wave 1 were much more likely to be excluded in Wave 2 and being excluded in Wave 2 increased the probability of being excluded in Wave 3. The pattern of exclusion over time (i.e., the odds ratios between each pair of waves) was the same across the three disability groups. Several pairwise comparisons between disability groups on each of the path coefficients were conducted with Satorra-Bentler scaled (mean-adjusted) chi-square tests, given that MLR was used for estimating all the models. The LD group had a statistically significant higher odds ratio in the pattern of exclusion from Wave 1 to Wave 2 than the EBD and ADHD groups (the chi-square difference statistics ranged from 6.15 to 41.47). Furthermore, the ADHD group had a statistically significant higher odds ratio in the pattern of exclusion from Wave 2 to Wave 3 than the LD and EBD disability groups (the chi-square difference statistics ranged from 4.62 to 6.21). Apart from these two Downloaded from ebx.sagepub.com by SAGE editorial on March 9, 2012 7 Bowman-Perrott et al. LD Wave 1 Exclusion 8.29* Wave 2 Exclusion 3.25* Wave 3 Exclusion 2.02* EBD Wave 1 Exclusion 2.45* Wave 2 Exclusion 3.74* Wave 3 Exclusion 5.83* Wave 3 Exclusion 1.22 ADHD Wave 1 Exclusion 4.14* Wave 2 Exclusion 1.75* *p<.05 Figure 1. Odds Ratios for Disciplinary Exclusion Over Time by Disability Group discrete patterns of exclusion, no statistically significant differences on any other patterns of exclusion were found among the three disability groups (the chi-square difference statistics ranged from 0.48 to 3.83). Predictors of Exclusion Status Over Time Student exclusion status across the three waves was predicted by identified variables in four conceptual categories: student demographic characteristics, family/household characteristics, student academic achievement and social skills, and school characteristics. As described earlier, the predictors included observed variables as well as unobserved or latent variables. For the latent variables, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to examine whether the observed items loaded onto the corresponding latent variables. All of the factor loadings were significant, and the standardized coefficients ranged from .47 to .96 across the four latent variables. Although the overall model chi-square (see Note 2) was significant, χ2(486) = 3,574.851, p < .05, various fit indices (CFI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.05, SRMR = 0.04) still suggested that the proposed measurement model with the four factors fitted the data adequately (Hu & Bentler, 1999). The factor scores for each of the four latent variables were subsequently computed and used in the analyses (Thompson, 2004). In other words, parental involvement, parent satisfaction with school, social adjustment, and school risk were represented by the corresponding factor scores and entered in the model. The hypothesized model with student exclusion status at different waves as the dependent variable was analyzed for the overall sample and separately for the three disability groups. Each odds ratio was transformed into effect size dHH (Hasselblad & Hedges, 1995) by LOR * 3 , where LOR is π the natural logarithm of the odds ratio and π = 3.14159 (Chinn, 2000). Given the relatively large sample size, many path coefficients were found to be statistically significant even though some of them might carry minimal effects. To filter out these minimal effects, results (see Note 3) are presented in Figure 2 and Table 2 only for odds ratios (a) that are statistically significant (α < .05) and (b) with effect sizes dHH > 0.10. Overall model. Three student characteristics variables were related to a higher probability of being excluded in Waves 1 and 2: disability status (EBD and ADHD), being African American, and gender (males) (see Figure 2). Among all of the student academic- and social-skillsrelated variables examined, social adjustment was the only variable that predicted exclusion status in both Waves 1 and 2. Students with higher social adjustment scores were less likely to be excluded. Two family/household characteristics variables, family structure and parent involvement, were associated with higher rates of exclusion in Wave 1. Students from non-two-parent families and students whose parents were more involved in school had a higher probability of being excluded. With all theoretically relevant variables accounted for in the model, early exclusion remained a statistically significant and strong predictor of later exclusion, with odds ratios of 2.45 and 3.72, as depicted in Figure 2. Disability status. Similar to the findings for the overall sample, for each disability group, males were more likely than females to be excluded in Waves 1 and 2 (see Table 2). Students with LD who were reported to have higher social adjustment scores had a lower probability of being excluded in Waves 1 and 2 than their counterparts with lower reported social adjustment scores. For students in the EBD and ADHD groups, few other variables in the model consistently predicted exclusion status over time. Notably, similar to the findings for the sample as a whole, for each disability group, early exclusion was a statistically significant and strong predictor of exclusion over time—even with all theoretically relevant variables included in the model. Predictors that did not meet dual criteria. It is worth noting for future research that two variables identified consistently in previous studies as associated with disciplinary exclusion—student age and SES risk—were significantly related to exclusion status over time in this study, but they were excluded from reported findings because their effect sizes were below .10. Older students were more likely to be excluded in Wave 1 (α < .05; dHH = .04) and Wave 2 (α < .05; dHH = .03). Students from families with higher scores Downloaded from ebx.sagepub.com by SAGE editorial on March 9, 2012 8 Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders XX(X) Disability Group EBD ADHD 2.49 2.03 2.04 School Characteristics Family/Household Characteristics SES Risk FS SM 1.93 PE †PI Urban †PS SC SR 1.75 3.02 2.45 Wave 1 Exclusion 1.83 AA 1.55 HIS 2.28 AGE 3.72 Wave 2 Exclusion 1.97 MALE 0.61 0.56 ACH Student Demographic Characteristics Wave 3 Exclusion EA GR PeI TI †SA Student Academic and Social Skills Figure 2. Odds Ratios for Predictor Variables Over Time Note. Only statistically significant (< .05) odds ratios with effect size dHH > 0.10 are presented. Odds ratios with values larger than 1.0 indicate higher probability of being excluded. †Variables are unobserved and measured by several observed variables. EBD = emotional/ behavioral disorders; ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. FS = Family Structure. SM = Student Mobility. PE = Parent Expectations. PI = Parent Involvement. PS = Parent Satisfaction with School. Urban = Urban School. SC = School Climate. SR = School Risk. AA = African American. HIS = Hispanic. ACH = Academic Achievement. EA = Extracurricular Activities. GR = Grade Retention. PeI = Peer Interactions. TI = Teacher Interactions. SA = Social Adjustment. on the SES risk variable also were more likely to be excluded at Wave 1 (α < .05; dHH = .06) and Wave 2 (α < .05; dHH = .04). Discussion The purpose of this study was to examine patterns and predictors of disciplinary exclusion over time for students with EBD, ADHD, and LD—three student groups that are consistently identified in the literature and in national reports to Congress as being most at risk of disciplinary exclusion. The longitudinal, nationally representative SEELS data set was used to: (a) investigate the relation of early exclusion (Wave 1) to later exclusion (Waves 2 and 3), and (b) examine the influence of student demographic characteristics, family characteristics, student academic and social skills, and school characteristics on rates of disciplinary exclusion over time. SEELS data were collected over a 6-year period with 1 to 2 years between waves. Given the study’s sample size, a conservative decision rule was adopted that included both statistical significance at conventional levels and an effect size greater than .10 in reporting the results. The findings from the current investigation provide the first national picture of the powerful predictive effect of early exclusion on later exclusion. Previously these data were only available from state- and district-level studies (Arcia, 2007; Krezmien et al., 2006). The present study extends the work of Achilles et al. (2007) by: (a) examining many of the same SEELS variables across all three waves of data (versus one point in time), (b) examining additional variables that have implications for educational practice (e.g., social adjustment), and (c) calculating and presenting effect sizes for all theoretically relevant variables to distinguish between statistical significance and the magnitude of the relationships between potential predictor variables and disciplinary exclusion over time. For the sample overall, and for the three disability groups separately, students excluded at Wave 1 were two to five times more likely to be excluded in Waves 2 and 3. Early exclusion was a statistically significant and strong predictor of later exclusion even when all theoretically relevant variables were accounted for in the model. This is significant, as it points to the impact of initial exclusion on a pattern of exclusion over time. That is, students who are Downloaded from ebx.sagepub.com by SAGE editorial on March 9, 2012 9 Bowman-Perrott et al. Table 2. Odds Ratios and Effect Sizes for Predictors of Interest Predictor DV = Time 1 Exclusion Disability (vs. LD) EBD ADHD Ethnicity (vs. Caucasian) African American Gender (Male) Family/Household Characteristics Family Structure Parent Involvementa Student Academic/Social Skills Peer Interactions Social Adjustmenta School Characteristics Urban School School Climate DV = Time 2 Exclusion Time 1 Exclusion Disability (vs. LD) EBD ADHD Ethnicity (vs. Caucasian) African American Gender (Male) Family/Household Characteristics Parent Involvementa Student Academic/Social Skills Social Adjustmenta DV = Time 3 Exclusion Time 2 Exclusion Ethnicity (vs. Caucasian) African American Hispanic Gender (Male) Student Academic/Social Skills Extracurricular Activities School Characteristics Urban School Overall LD EBD 3.02 (0.26) 2.03 (0.17) 1.83 (0.15) 2.28 (0.20) 4.31 (0.35) 1.81 (0.14) 1.93 (0.16) 1.75 (0.13) 1.87 (0.15) 2.15 (0.18) 2.24 (0.19) 0.56 (0.14) 5.62 (0.41) 2.70 (0.24) 0.56 (0.14) 0.41 (0.22) 1.81 (0.14) 0.37 (0.24) 1.65 (0.12) 2.45 (0.21) ADHD 4.80 (0.38) 1.97 (0.16) 1.55 (0.11) 1.97 (0.16) 2.41 (0.21) 1.74 (0.13) 0.61 (0.12) 0.51 (0.16) 3.72 (0.32) 2.54 (0.22) 2.49 (0.22) 2.03 (0.17) 3.95 (0.33) 2.01 (0.17) 0.57 (0.14) 2.02 (0.17) 1.67 (0.12) 1.67 (0.12) 2.18 (0.19) 2.08 (0.18) 0.56 (0.14) 4.96 (0.38) Table entries are statistically significant (a< .05) odds ratios with effect size dHH > 0.10. Odds ratios with values larger than 1.0 indicate higher probability of being excluded. Effect size dHH is computed using Hasselblad and Hedges’s (1995) equation. LD = learning disabilities; EBD = emotional/behavioral disorders; ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; SES = socioeconomic status. a.Variables are unobserved and measured by several observed variables. suspended or expelled once are likely to be suspended or expelled multiple times. Similar to earlier research (e.g., Achilles et al., 2007; Wagner et al., 2004), the present study documents that students with EBD were at the greatest risk of initial disciplinary exclusion, followed by students with ADHD and students with LD. When patterns of exclusion were examined, few statistically significant differences between the three student disability groups were found in their odds of being excluded over time. There was one notable exception: Students with LD had a statistically significant higher odds ratio in their pattern of disciplinary exclusion from Wave 1 to Wave 2 than students in the EBD and ADHD groups. In this study, students with LD excluded in Wave 1 were over eight times more likely to be excluded again in Wave 2. When other theoretically relevant variables were accounted Downloaded from ebx.sagepub.com by SAGE editorial on March 9, 2012 10 Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders XX(X) for in the model, a slightly different perspective on disciplinary exclusion emerged. Students in the EBD and the ADHD groups were significantly more likely than students in the LD group to be excluded in Wave 1 and Wave 2. These findings warrant further inquiry, as understanding the types and consequences of behavioral infractions leading to exclusion (and how they differ across the three disability groups) is important for better understanding disciplinary exclusion. Several variables were related to higher rates of disciplinary exclusion over time: being male, being African American, parent involvement, and poor social adjustment. Each variable contributed unique and significant variance to the prediction of disciplinary exclusion when all variables were accounted for in the model. Being male was a strong consistent predictor of disciplinary exclusion for the sample as a whole and for each disability group in Wave 1 and Wave 2 and for students with LD in Wave 3. Males were two to four times more likely than females to be excluded over time. For the sample overall, African American students were almost two times more likely than students in other ethnic groups to be excluded in Waves 1 and 2. African American ethnicity was also related to exclusion for students in the ADHD group in Wave 1 and for students in the LD group in Wave 3. The unique contribution of gender (males) and ethnicity (African American students) to exclusion status over time extends current research (Achilles et al., 2007; Skiba et al., 2002; Snyder & Sickmund, 2006). Achilles et al. (2007) noted that “the relationship between African American ethnicity and school exclusion has been repeatedly demonstrated but remains poorly understood” (p. 41). Perhaps more closely examining additional student, family, and school variables will provide insight into other factors that may be at work in the relationship between ethnicity and disciplinary exclusion. In the current study, higher levels of parent involvement were related to higher rates of exclusion for the overall sample and for students with LD and EBD in Wave 1 and for students with ADHD in Wave 2. This finding was somewhat counterintuitive and may suggest that parents were involved in ways (e.g., attending a conference related to problem behaviors) that were not described in the definition of the SEELS variable (e.g., attending an IEP meeting). In fact, Duchnowski and Kutash (in press) surveyed parents about their involvement in their children’s schools; results indicated that parents attended meetings at their children’s schools. However, the majority of those meetings were described as “negative” and as being related to “discipline issues” (p. 25). Results of their study point to “the need for a more comprehensive measure of this construct” (p. 24). Among the student academic and social skills variables examined, positive social adjustment was strongly predictive of lower rates of disciplinary exclusion in Waves 1 and 2. Social adjustment was a composite variable extracted from the SEELS data set. A student’s social adjustment score was based on teacher ratings of 11 items that addressed areas such as how well the student got along with peers and how well the student avoided situations that might result in trouble. Positive social skills have been shown to be related to ease of transition into kindergarten (Carlson et al., 2009) and middle school (Crockett, Losoff, & Petersen, 1984) and transition to postsecondary life (Kohler & Field, 2003). Some research (Meyer & Farrell, 1998; Raffaele Mendez et al., 2002) suggests that social skills instruction is associated with lower suspension rates. However, there is little empirical research on the relationship between student social skills and disciplinary exclusion. This is a topic worthy of further examination. Limitations There are two main limitations to the present study. First, parent-report data from the SEELS data set provided information for several of the variables examined, including the dependent variable disciplinary exclusion. However, this method is used in virtually all follow-up studies conducted in special education that have relied on self-report for a majority of the data collected (Bullis, Bull, Johnson, & Peters, 1994; Levine & Edgar, 1994). Furthermore, selfreport data from parents and from students with disabilities who leave school will be used extensively by states as they implement new postschool outcomes reporting requirements under Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) (Falls & Unruh, 2009). Nevertheless, self-report data raise concerns about the accuracy of the information provided. For example, accuracy can be affected if the respondent feels compelled to provide a socially desirable response. In this study, to the extent that some parents felt it was undesirable to report their student as having been suspended or expelled in the previous school year, it is possible that rates of disciplinary exclusion are underreported. Accuracy of information can also be affected by a lack of knowledge or recall by the respondent. Research (e.g., Bullis et al., 1994) indicates that while parents provide less accurate information on details (e.g., hourly wages), they are good respondents for macroevents about their sons and daughters (e.g., employment), as reflected in high levels of agreement among parents, students, and teachers for macro-events and factual information. Moreover, parents can accurately recall and report factual information about their children for several years with the highest rates of accuracy occurring for up to 2 years (Robbins, 1963). The variables investigated in this study were largely factual (e.g., parent report of student mobility) or the perceptions of respondents (e.g., parent report of student interactions with peers), and the time frame for recalling information for data collected in each wave was no more than 1 to 2 years. Downloaded from ebx.sagepub.com by SAGE editorial on March 9, 2012 11 Bowman-Perrott et al. Second, the study used the extant data set from the SEELS study to investigate patterns and predictors of disciplinary exclusion over time. Large, longitudinal data sets permit multivariate investigations of important issues across time. However, the breadth of such databases can limit the depth of information on any specific variables of interest. That was the case in this study. For example, the SEELS data set did not include information on the reasons for or length of time students were suspended or expelled. Such information could permit a more in-depth understanding of patterns of exclusion over time. Nonetheless, the present study provides a “first look” at patterns and predictors of disciplinary exclusion over time based on a longitudinal, nationally representative data set that extends current research on disciplinary exclusion and provides several implications for policy, practice, and future research. Implications for Policy and Practice Without question, schools have a responsibility to create safe and disciplined learning environments so that teachers can teach and students can learn. Furthermore, school personnel have a responsibility to evaluate policies and practices to ensure they are achieving their intended outcomes. The disproportionate application and multiple poor outcomes associated with disciplinary exclusion found in the literature, as well as the patterns and predictors of exclusion over time identified in the present study, highlight the importance of implementing school policies and practices that reduce the likelihood of initial disciplinary exclusion. To start, district and school discipline policies should be examined to ensure that (a) definitions of suspension and expulsion are clear, (b) behavioral infractions that warrant suspension and expulsion are clearly stated, (c) procedures are clearly stated (e.g., written notification to parents/ guardians), (d) measures are in place to ensure that alternatives are exhausted so that disciplinary exclusion measures are a “last resort,” and (e) disciplinary exclusion is part of a comprehensive school-wide approach to behavior and discipline that emphasizes prevention and creates options for excluded students to remain connected to the learning process (American Psychological Association [APA] Zero Tolerance Task Force, 2008; Brown, 2007; Horner, Sugai, Todd, & Lewis-Palmer, 2005). Schools can play a major role in connecting the teaching of social skills to instruction. Social skills are an important component of social adjustment (Sumi, Marder, & Wagner, 2005). They include those communication, problem-solving, decision-making, self-management, and peer relations abilities that allow students to initiate, build, and maintain positive social relationships with others. These are skills that can, and should, be taught in school. This is particularly important for students with EBD and ADHD (Sumi et al., 2005). Modeling and practicing these skills is critical, as deficits or excesses in social behavior interfere with learning, teaching, and the classroom’s orchestration and climate. Students’ social competence is linked to peer acceptance, teacher acceptance, successful inclusion efforts with students with disabilities, and post-school success. Implications for Research Longitudinal, prospective research that examines the implementation and impact of disciplinary exclusion practices is needed. Future research might further investigate the relationships among certain student and family demographic characteristics and disciplinary exclusion and the circumstances that place some students at greater risk of exclusion both initially and over time. Are some students in double or triple jeopardy of exclusion? Wagner and Cameto (2004) reported that youth with EBD are more likely to be involved in fights or with bullying at, on their way to, or on their way home from school. Some students identified with EBD in later school years were first identified as LD in earlier grades (Duncan, Forness, & Hartsough, 1995), some have concurrent EBD and LD diagnoses (Lopes, 2005), and some experience comorbid LD, EBD, and ADHD diagnoses (Dietz & Montague, 2006). Moreover, several demographic characteristics associated with disciplinary exclusion (e.g., male gender, African American ethnicity, low family SES) are also documented characteristics of youth with EBD (Wagner, 2004). What circumstances in schools place students with specific risk factors in jeopardy of exclusion? What can schools do to create systems that monitor discipline practices and their impact on students at greater risk of exclusion? Increasingly, it is being recommended that disciplinary exclusion measures be implemented within the context of multitier school-wide discipline models (e.g., APA Zero Tolerance Task Force, 2008). Recent research indicates that school-wide discipline systems, such as school-wide Positive Behavioral Intervention and Support Systems, can lead to reductions in suspensions and increases in academic achievement among elementary school students (Bradshaw, Mitchell, & Leaf, 2010). It is not clear, however, if the implementation of school-wide discipline systems will necessarily lead to reductions in the disproportionate application of disciplinary exclusion practices among students most at risk for exclusion (e.g., students with EBD, ADHD, male students, and African American students). For example, some research suggests that school personnel do not readily access and use information on rates of disciplinary office referrals by ethnicity even when such reports are available (Vincent, 2008). What conditions are necessary for school personnel to use discipline data to evaluate the implementation and impact of policies and practices on specific student groups? What impact does a multitier, schoolwide approach to discipline have on patterns of exclusion Downloaded from ebx.sagepub.com by SAGE editorial on March 9, 2012 12 Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders XX(X) over time? What strategies within primary, secondary, and tertiary tiers have the greatest success in reducing rates of exclusion among students at highest risk of suspension and expulsion? What strategies are most successful in keeping excluded students connected to the learning process? Finally, given the relation of parent involvement to disciplinary exclusion, examining factors such as the quality of parent interaction or involvement should be taken into account (Duchnowski & Kutash, in press). This multidimensional variable should be further investigated to go beyond how many meetings or conferences parents attended to include the purpose for and quality of such involvement— as well as its impact on student outcomes. Answers to questions such as these about the implementation and impact of disciplinary exclusion within the context of school-wide discipline systems may provide insights into the patterns of exclusion over time and into strategies that can reduce the disproportionate use of and adverse consequences associated with disciplinary exclusion. Declaration of Conflicting Interests The authors declared no potential conflicts of interests with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article. Funding The authors received no financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article. Notes 1. A table detailing the items extracted from the SEELS data set, including the item name, values, scoring, data source, and correlation matrices for the present study, is available from the first author upon written request. 2. All chi-square values presented in the results section were adjusted for all other variables. 3. All of the findings (odds ratios and effect sizes) for the entire sample, for each disability group, and for all three waves of data are available from the first author. References Achilles, G. M., McLaughlin, M. J., & Croninger, R. G. (2007). Sociocultural correlates of disciplinary exclusion among students with emotional, behavioral, and learning disabilities in the SEELS national dataset. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 15, 33-45. Amato, P. R. (2001). Children and divorce in the 1990s: An update of the Amato and Keith (1991) meta-analysis. Journal of Family Psychology, 15, 355-370. American Psychological Association Zero Tolerance Task Force. (2008). Are zero tolerance policies effective in the school? An evidentiary review and recommendations. American Psychologist, 63, 852-862. Arcia, E. (2007). Variability in schools’ suspension rates of black students. The Journal of Negro Education, 76(4), 597-609. Blackorby, J., Knokey, A., Wagner, M., Levine, P., Schiller, E., & Sumi, C. (2007). SEELS: What makes a difference? Influences on outcomes for students with disabilities. Retrieved from http://www.seels.net/infoproduct.htm Bradshaw, C. P., Mitchell, M. M., & Leaf, P. J. (2010). Examining the effects of school-wide positive interventions and supports on student outcomes: Results from a randomized controlled effectiveness trial in elementary schools. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 12, 133-148. Brown, T. M. (2007). Lost and turned out: Academic, social and emotional experiences of students excluded from school. Urban Education, 42(5), 432-455. Bullis, M., Bull, B., Johnson, B., & Peters, D. (1994). Respondents who are hearing and deaf in a transition study: Did they supply data similar to their parents? Exceptional Children, 60, 323-333. Carlson, E., Daley, T., Bitterman, A., Heinzen, H., Keller, B., Markowitz, J., & Riley, J. (2009). Early school transitions and the social behavior of children with disabilities: Selected findings from the Pre- Elementary Education Longitudinal Study. Rockville, MD: Westat. Retrieved from https://www. peels.org/Docs/Early%20School%20Transitions%20and%20 the%20Social%20Behavior%20of%20Children%20with%20 Disabilities.pdf Chinn, S. (2000). A simple method for converting an odds ratio to effect size for use in meta-analysis. Statistics in Medicine, 19, 3127-3131. Christle, C. A., Jolivette, K., & Nelson, C. M. (2005). Breaking the school to prison pipeline: Identifying school risk and protective factors for youth delinquency. Exceptionality, 13(2), 69-88. Christle, C. A., Nelson, C. M., & Jolivette, K. (2004). School characteristics related to the use of suspension. Education and Treatment of Children, 27(4), 509-526. Clark, D. M., Petras, H., Kellam, S. G., Ialongo, N., & Poduska, J. M. (2003). Who’s most at risk for school removal and later juvenile delinquency? Effects of early risk factors, gender, school/community poverty, and their impact on more distal outcomes. Women & Criminal Justice, 12(2/3), 89-116. Cooley, S. (1995). Suspension/expulsion of regular and special education students in Kansas: A report to the Kansas State Board of Education. Topeka: Kansas State Board of Education. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 393 403) Crockett, L. J., Losoff, M., & Petersen, A. C. (1984). Perceptions of the peer group and friendship in early adolescence. Journal of Early Adolescence, 4, 155-181. Dawson, D. A. (1991). Family structure and children’s health and well-being: Data from the 1988 National Health Interview Survey on Child Health. Journal of Marriage and Family, 53(3), 573-584. Dietz, S., & Montague, M. (2006). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder cormorbid with emotional and behavioral disorders and learning disabilities in adolescents. Exceptionality, 14(1), 19-33. Downloaded from ebx.sagepub.com by SAGE editorial on March 9, 2012 13 Bowman-Perrott et al. Duchnowski, A. J., & Kutash, K. (in press). School reform and mental health services for students with emotional disturbances educated in urban schools. Education and Treatment of Children. Duncan, B. B., Forness, S. R., & Hartsough, C. (1995). Students identified as seriously emotionally disturbed in school-based day treatment: Cognitive, psychiatric, and special education characteristics. Behavioral Disorders, 20(4), 238-252. Falls, J., & Unruh, D. (2009, October). Frequently asked questions: Revised Part B Indicator 14 post-school outcomes. Retrieved from www.psocenter.org Gregory, A., Skiba, R. J., & Noguera, P. A. (2010). The achievement gap and the discipline gap: Two sides of the same coin? Educational Researcher, 39(1), 59-68. Grosenick, J. K., Huntze, S. L., Kochan, B., Peterson, R. L., Robertshaw, C. S., & Wood, F. H. (1981). National needs analysis in behavior disorders working paper: Disciplinary exclusion. Washington, DC: Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services. (ERIC Document Reproduction No. 215 540) Hasselblad, V., & Hedges, L. V. (1995). Meta-analysis of screening and diagnostic test. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 167-178. Horner, R. H., Sugai, G., Todd, A. W., & Lewis-Palmer, T. (2005). School-wide positive behavior support: An alternative approach to discipline in schools. In L. M. Bambara & L. Kern (Eds.), Individualized supports for students with problem behaviors (pp. 359-390). New York: Guilford. Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1-55. Kohler, P. D., & Field, S. (2003). Transition-focused education: Foundation for the future. Journal of Special Education, 37, 174-183. Krezmien, M. P., Leone, P. E., & Achilles, G. M. (2006). Suspension, race, and disability: Analysis of statewide practices and reporting. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 14(4), 217-226. Leone, P. E., Christle, C. A., Nelson, C. M., Skiba, R., Frey, A., & Jolivette, K. (2003). School failure, race, and disability: Promoting positive outcomes, decreasing vulnerability for involvement with the juvenile delinquency system. Retrieved from http://www.edjj.org Levine, P., & Edgar, E. (1994). An analysis of respondent agreement in follow-up studies of graduates of special and regular education programs. Exceptional Children, 60, 334-343. Lopes, J. (2005). Intervention with students with learning, emotional and behavior disorders: Why do we take so long? Education and Treatment of Children, 28(4), 345-360. McFadden, A. C., Marsh, G. E., Price, B. J., & Hwang, Y. (1992). A study of race and gender bias in the punishment of handicapped school children. Urban Review, 24, 239-251. Meyer, A. L., & Farrell, A. D. (1998). Social skills training to promote resilience in urban sixth-grade students: One product of an action research strategy to prevent youth violence in highrisk environments. Education and Treatment of Children, 21, 461-488. Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2007). Mplus user’s guide (5th ed.). Los Angeles: Author. Raffaele Mendez, L. M., & Knoff, H. M. (2003). Who gets suspended from school and why: A demographic analysis of schools and disciplinary infractions in a large school district. Education and Treatment of Children, 26(1), 30-51. Raffaele Mendez, L. M., Knoff, H. M., & Ferron, J. M. (2002). School demographic variables and out of school suspension rates: A quantitative and qualitative analysis of a large, ethnically diverse school district. Psychology in the Schools, 39(3), 259-277. Rausch, M. K., & Skiba, R. (2004). Unplanned outcomes: Suspensions and expulsions in Indiana. Education Policy Briefs, 2(2), 1-7. Reschly, A., & Christenson, S. L. (2006). Prediction of dropout among students with mild disabilities: A case for the inclusion of student engagement variables. Remedial and Special Education, 27, 276-292. Robbins, L. (1963). The accuracy of parental recall of aspects of child development and of child rearing practices. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 66, 261-270. Rocque, M. (2010). Office discipline and student behavior: Does race matter? American Journal of Education, 116, 557-581. Schnoes, C., Reid, R., Wagner, M., & Marder, C. (2006). ADHD among students receiving special education services: A national survey. Exceptional Children, 72, 483-496. Simpson, G. A., & Fowler, M. G. (1994). Geographic mobility and children’s emotional/behavioral adjustment and school functioning. Pediatrics, 93(2), 303-309. Skiba, R. J. (2000). Zero tolerance zero evidence: An analysis of school disciplinary practice (Policy Research Report #SRS2). Terry Haute: Indiana University, Indiana Education Policy Center. Skiba, R. J., Michael, R. S., Nardo, A. C., & Peterson, R. L. (2002). The color of discipline: Sources of racial and gender disproportionality in school punishment. The Urban Review, 34(4), 317-342. Skiba, R. J., Peterson, R. L., & Williams, T. (1997, August). Office referrals and suspension: Disciplinary intervention in middle schools. Education and Treatment of Children, 20(3), 1-21. Skiba, R., & Sprague, J. (2008, September). Safety without suspensions. Educational Leadership, 66(1), 38-43. Skiba, R. J., Wu, T. C., Kohler, K., Chung, C., & Simmons, A. B. (2001). Disproportionality and discipline among Indiana’s students with disabilities: A status report. Terre Haute: Indiana University, Indiana Education Policy Center. Snyder, H. N., & Sickmund, M. (2006). Juvenile offenders and victims: 2006 National report. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. Sumi, C., Marder, C., & Wagner, M. (2005). The social adjustment of elementary and middle school students with disabilities. In Engagement, academics, social adjustment, and independence: The achievements of elementary and middle school students with disabilities. Menlo Park, CA: SRI International. Downloaded from ebx.sagepub.com by SAGE editorial on March 9, 2012 14 Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders XX(X) Retrieved from http://www.seels.net/designdocs/engagement/ All_SEELS_outcomes_10-04-05.pdf Sundius, J., & Farneth, M. (2008). Putting kids out of school: What’s causing high suspension rates and why they are detrimental to students, schools, and communities (Policy Paper #2 in OSI-Baltimore’s Student Attendance Series). Baltimore: Open Society Institute. Thompson, B. (2004). Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis: Understanding concepts and applications. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Tyler, K. A., & Bersani, B. E. (2008). A longitudinal study of precursors to running away in early adolescence. Journal of Early Adolescence, 28(2), 230-251. U.S. Department of Education. (2002). Twenty-fourth annual report to Congress on the implementation of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. Washington, DC: Office of Special Education Programs. U.S. Department of Education. (2003). Twenty-fifth annual report to Congress on the implementation of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. Washington, DC: Author. U.S. Department of Education. (2007a). Status and trends in the education of racial and ethnic minorities. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics. U.S. Department of Education (2007b). Indicators of school crime and safety: 2007. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics. U.S. Department of Education. (2007c). 27th Annual Report (2005) report to Congress on the implementation of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, Vol. 2. Washington, DC: Office of Special Education Programs. Vincent, C. G. (2008, November). Evaluation brief: Do schools using SWIS take advantage of the “school ethnicity report”? Retrieved from http://pbis.org/evaluation/evaluation_briefs/ default.aspx Wagner, M. M. (2004). Outcomes for youths with serious emotional disturbance in secondary school and early adulthood. The Future of Children, 5(2), 90-112. Wagner, M., & Cameto, R. (2004). The characteristics, experiences, and outcomes of youth with emotional disturbances. NLTS2 Data Brief, 3(2), 1-8. Wagner, M., Kutash, K., Duchnowski, A. J., & Epstein, M. H. (2005). The Special Education Elementary Longitudinal Study and the National Longitudinal Transition Study: Study designs and implications for youth with emotional disturbance. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 13(1), 25-41. Wagner, M., Marder, C., Blackorby, J., & Cardoso, D. (2002). The children we serve: The demographic characteristics of elementary and middle school students with disabilities and their households. Menlo Park, CA: SRI International. Wagner, M., Newman, L., & Cameto, R. (2004). Changes over time in the secondary school experiences of students with disabilities: A special topic report of findings from the National Longitudinal Transitional Study-2 (NLTS2). Menlo Park, CA: SRI International. Whitbeck, L., & Hoyt, D. (1999). Nowhere to grow: Homeless and runaway adolescents and their families. New York: Aldine de Gruyter. Zhang, D., Katsiyannis, A., & Herbst, M. (2004). Disciplinary exclusions in special education: A four-year analysis. Behavioral Disorders, 29, 337-334. About the Authors Lisa Bowman-Perrott, PhD, is an assistant professor of special education at Texas A&M University. Her interests include school discipline and interventions for students with or at risk for emotional and behavioral disorders. Michael R. Benz, PhD, is a professor of special education and Director of the Center on Disability and Development at Texas A&M University. His interests include secondary, transition, and postschool outcomes. Hsien-Yuan Hsu, PhD, is an assistant research fellow in the Center of Educational Research and Evaluation at National Taiwan Normal University. His interests include large-scale data analysis, multilevel modeling, and web survey. Oi-man Kwok, PhD, is an associate professor of research, measurement, and statistics at Texas A&M University. His interests include longitudinal data analysis using multilevel models and structural equation models and the applications of these models in educational and psychological research. Leigh Ann Eisterhold, MEd, is a doctoral student at Texas A&M University. Her interests include family involvement of students with disabilities. Dalun Zhang, PhD, is an associate professor of special education at Texas A&M University. His interests include transition, selfdetermination, and prevention of juvenile offence. Downloaded from ebx.sagepub.com by SAGE editorial on March 9, 2012