Volume 7 No. 1 April 2002

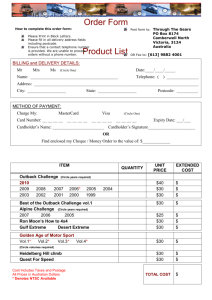

advertisement