Generalists versus Specialists: Managerial Skills and CEO Pay

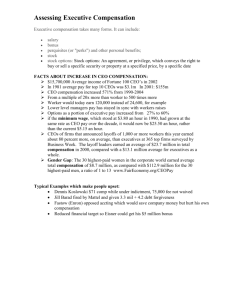

advertisement