VIOLATING THE CODE: INMATES‟ JUSTIFICATIONS FOR

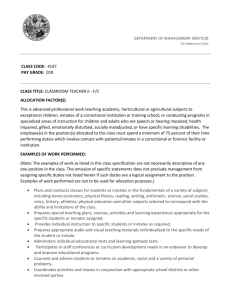

advertisement