Public transport

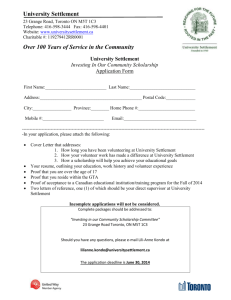

advertisement