Exposure Draft – Attestation and Direct Engagements

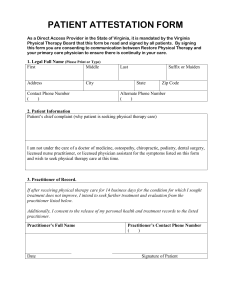

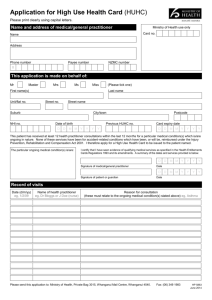

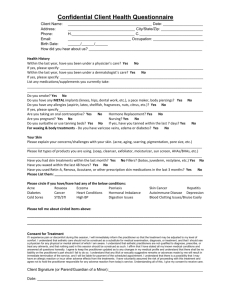

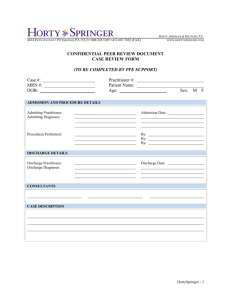

advertisement