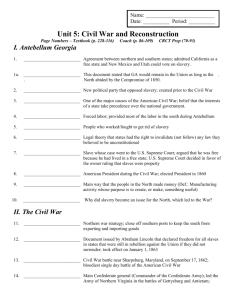

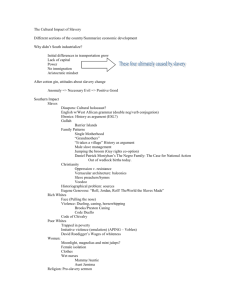

panel i: thirteenth amendment in context

advertisement