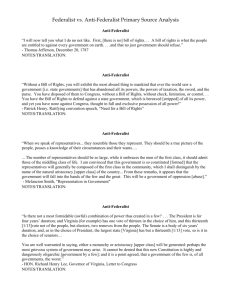

MISUNDERSTANDING THE ANTI-FEDERALIST PAPERS: THE

advertisement