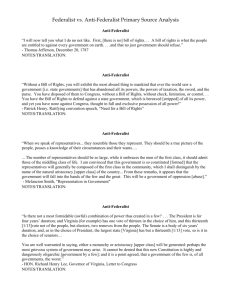

The Essential Anti-Federalist Papers

advertisement