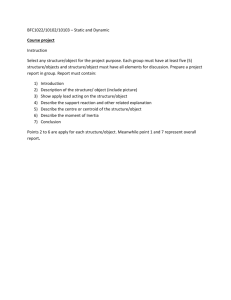

Sample answer to Question Two: The Stevens Case

advertisement

Sample answer to Question Two: The Stevens Case Note to students: The first sample answer is very short, reflecting the fact that this was a 45 minute essay question. The second sample answer goes into more detail, as many of you did when critically assessing one or more of the trial court’s three reasons. Short sample answer Reason #1. The trial court [TC]’s statement of Reason #1 fails to supply convincing authorizing reasons for giving the evaluative language of §9 an application distinct from and probably in conflict with the meaning and application that Stevens [S] particularly intended. TC treats the phrase “acting… like a lady should” in §9 of the will as a court might treat a legal standard in a statute, common law rule, or constitutional provision (“cruel punishment,” “best interests of the child,” “reasonable precautions.”) As with a legal standard, TC tries to give §9 the morally or socially best reading, which need not be the application that the lawmaker had in mind. But a will, like a contract, is probably different from a statute or other legal rule. When a lawmaker chooses to make legal policy by means of a standard rather than a rule, the lawmaker arguably authorizes courts to carry out normative reasoning when filling out the standard. But a testator may not be delegating such a power to a court that interprets and applies a will. A testator might intend his or her own particular intentions to govern. Still, S could have chosen to write §9 in a more rule-like way (dresses, not pants; dancing, not calculus), which would have left less interpretive room for the court. In choosing a standard rather than rules, S arguably delegated at least some interpretive discretion to the court. Even if the wording of §9 does delegate some interpretive discretion, TC does a poor job of filling out the standard’s meaning. TC’s correct observation that A has done nothing to regret or apologize for doesn’t helpfully fill out the meaning of “acting like a lady should.” Reason #2. In declining to enforce §9 on the grounds that it is sex-discriminatory and therefore contrary to public policy, TC might claim to be following Dworkin’s nonpositivist interpretation of Riggs v. Palmer, in which the NY court declined to permit a murderer to take under his victim’s will, even though no such exception was provided for in the relevant statutes. Dworkin argues that the Riggs court acted with integrity, because it enforced the legal rules in light of the relevant legal principles, including the principle that no one may profit from their own wrong. But in order for a court to act with integrity, it must treat like cases alike. TC doesn’t explain how non-enforcement of §9 is consistent with the other judicial decisions enforcing discriminatory terms. If TC is “stiff-arming” the law, legal-realist fashion, then reason #2 doesn’t satisfy Scalia’s description of legitimate stiff-arming, for two reasons. First, TC doesn’t distinguish the cases. Second, the law of wills is statutory, and Scalia’s paradigm of the stiff-arming judge is the judge evolving the common law. TC doesn’t explain how reason #2 is consistent with the rights of testators to dispose of their property – a right that might illustrate Hart’s will theory (in which the right-holder has a sovereign power of control, one which correlates to duties in others). TC offers no plausible generalization about the limits of testator sovereignty. Absent such a justification, the decision not to enforce §9 seems ad hoc and contrary to the generality and consistency requirements of the rule of law. Reason #3. TC’s third reason is that in his last months, S became more accepting of A. Two problems for this reason are: (1) what is the relation between S’s change of heart and the terms of the will, and (2) has the TC established an adequate factual basis for concluding that S became more accepting of A (in a way that is legally relevant to the terms of S’s will)? (1). TC might mean that S waived §9 or revoked it. But this might require a formality of some kind. Alternatively, TC might mean that S’s end-of-life acceptance of A satisfies the conditions laid down in §9. But that way of reading §9 conflicts with the reading of §9 in Reason #1. “Acceptance” satisfies §9 only if “acting like a lady should” means “acting in whatever way S accepts.” (2). TC has not made a convincing showing that the facts support the conclusion that S changed his mind about A and became more accepting of her. His reaction to her threat to launch a malpractice suit against his doctor is consistent with his prior rejection of assertive, lawyerly roles for A. Of course, S could have been displeased by the malpractice threat for reasons having to do with his illness. And we as an appellate court should defer to the trial court’s factual findings. TC invokes the “Little Mermaid” [LM] story as if it corroborated TC’s interpretation of the facts. The story is more relevant, though, to the normative question about how a father should act toward his daughter, than it is to the factual question about how S actually did act toward A. Some might dismiss recourse to LM because it is not a law source. That might be somewhat simplistic, though, because some stories can reveal the legal principles (themselves “unenacted”) that illuminate the law, placing the law in the light of coherent and valuable principles and policies. Judge Fernandez’s invocation of “A Christmas Carol” in Phillip Becker might illustrate how a story can bring out and serve law’s value commitments. But the point of retelling “A Christmas Carol” in Phillip Becker was to shed light on who the judge must be when deciding a heartbreaking case. LM is different in this respect. It is about the father-daughter relationship, not about the role of the judge. Hence it seems less apt as a judicial narrative. Though TC’s choice of the Disney version of LM might seem merely outcomedriven, TC might try to justify reliance on the Disney version by explaining that it, better 2 than the Andersen version, expresses conventional contemporary values that the court should take seriously when exercising its discretion. (But this again raises the question, already discussed, of how much or what kind of judicial discretion is authorized, either by the language of §9, or by the best account of the law of wills.) Long (more detailed) sample answer Clause §9 – which provides that Arabella [A] shall not receive her share unless, by the time of Stevens’ [S] death, “she starts acting more like a lady should” – is more like a standard than a rule. Like a standard, §9 calls for some form of evaluative assessment (applying the criterion “acting like a lady should”), and requires the exercise of judgment in order to locate facts on degree-vague continua (“starts acting,” “more”). Like a standard, §9’s application requires close attention to factual particulars. The standard-like rather than rule-like wording of §9 bears on our assessment of the trial court’s [TC] three reasons. Reason #1. Here, TC interprets and applies §9 as if it were a legal standard in a statute, common law rule, or provision of a constitution. The meaning of such legal standards is not fixed by the lawmaker’s intentions – certainly not their particular intentions. When a court applies the Constitution’s prohibition against “cruel punishments,” for example, its job is not limited to reproducing the Framers’ own judgments about what is and isn’t cruel. The court is entitled, even required, to look into the qualities that truly make punishment cruel. Similarly, when interpreting and applying §9, TC does not feel constrained by the applications that S had in mind. Instead, TC tries to give §9 a “best lights” interpretation and application. But do normative-evaluative words and phrases in a will similarly supply authorizing reasons for courts to look into the moral issue? In part, legal standards in statutes or constitutions supply authorizing reasons for judicial value-judgments because the statute or constitution is meant to govern for a long time, perhaps many generations. What someone “should” do, like what is “reasonable” or “cruel” or in a child’s “best interests,” needs to be determined in a way that is not too tethered to the lawmaker’s own time-bound judgments. In choosing to enact a standard rather than a rule, the lawmaker knows that it is delegating an evaluative power to future courts. These authorizing reasons for judicial value-judgments are weaker when the standard is in a private instrument such as a will. The testator reasonably wants his own wishes to govern in the near horizon, and in drafting a standard does not mean to delegate much interpretive-evaluative freedom to a court. But this is a distinction in degree, not in kind, and S should have known that he could exert a firmer grip from beyond the grave 3 by stating his wishes in the form of rules (no inheritance if during a stated probationary period A wears pants, etc.) Even if TC may legitimately treat clause §9 as a standard, TC does a poor job of filling out the standard’s meaning. TC’s correct observation that A has done nothing to regret or apologize for doesn’t helpfully fill out the meaning of “acting like a lady should.” TC’s statement of Reason #1 fails to supply convincing authorizing reasons for giving the evaluative language of §9 an application distinct from and probably in conflict with the meaning and application that S particularly intended. Reason #2. If the law is exhausted by the rules promulgated by the legislature and by the holdings in prior case law, then TC’s refusal to enforce §9 is contrary to the rule of law (inconsistent, retroactive, non-congruent, etc.) and to the role of the judiciary. In a nonpositivist view, though, principles also count as law sources (Dworkin). Reason #2 is similar to Dworkin’s interpretation of Riggs v. Palmer, in which the NY court declined to permit a murderer to take under his victim’s will, even though no such exception was provided for in the relevant statutes. To model our case on Riggs, Dworkin would reframe the normative ground of anti-discrimination, restating TC’s “public policy” as a matter of principle (similar to TC’s “principle of equal rights for all”). He would then show how adherence to the equal rights principle also satisfies the principle that like cases should be treated alike. TC does not make this showing. We aren’t told why A has a right to win our case under the principle that best fits and justifies the existing case law. While the Riggs court could show how the principle that “no one may profit from their own wrong” harmonizes with the point of the law of wills, TC makes no such showing in relation to the equal rights principle. Instead, it seems that TC is taking a page out of Scalia’s common-law playbook, and stiff-arming the law sources with which he disagrees (though unlike Scalia’s common law judge, TC doesn’t skillfully distinguish the cases that come out the other way). TC is correct that sometimes courts “take a step forward” to advance some principle or policy crucial to the law. We saw that in our sequence of common law products liability cases. But because the law of wills is statutory in this state, the TC needs to show how “taking a step forward” is consistent with the judicial role in a statutory field. TC hasn’t made that showing. TC argues that while S has a right to control the disposition of his property, he has no right to render the court complicit in his discrimination. The standard-like wording of §9 strengthens this argument. If §9 stated bright-line tests, such as “dresses, not pants,” or “dancing, not calculus,” the court’s role in applying §9 to the facts would be more straightforward. The court would still be the agent of the testator’s discrimination; but 4 the court would not have to imaginatively occupy and fill out a discriminatory worldview, as judicial enforcement of the “ladylike” standard requires. A court might decline to enforce a term that leaves the estate to the children “so long as they act like good Nazis,” even if the court must enforce a term that disinherits a child for marrying a Jew. TC doesn’t sufficiently explain what kind of interest, value, or other consideration is weighty enough to justify limiting or abridging the testator’s right to control the disposition of his property. If the testator’s right is best supported by the interest theory, we may properly take into account not only the third-party harms caused by stereotype reinforcement, but also perhaps A’s own needs as a minor child. (Is state law obligated to permit a parent to disinherit his or her minor child, and if so, can this be done for any reason at all?) The testator’s right seems a good match for the will theory, as an exercise of the property owner’s sovereignty. Even here, though, there would seem to be sufficient reasons for the state to limit that sovereignty. (Must the state enforce my wish that my Rembrandts be burned after my death?) Reason #2’s greatest deficiency is its failure to adhere to the constraint of integrity in offering a rational reconstruction of the law that both fits the law sources and brings out their point or purpose. Reason #3. TC’s third reason is that in his last months, S became more accepting of A. Two problems for this reason are: (1) what is the relation between S’s change of heart and the terms of the will, and (2) has the TC established an adequate factual basis for concluding that S became more accepting of A (in a way that is legally relevant to the terms of S’s will)? Problem 1. TC might think either that the terms of §9 make S’s change of heart relevant to A’s share in the estate, or that S’s change of heart constitutes a waiver or revocation of the §9 requirement. The former connection is implausible. “More accepting” is not the standard that §9 lays out. In equating the meaning of “acting more like a lady should” with “whatever behavior S accepted,” TC here contradicts the approach that TC took in reason #1 (which treats “ladylike” as a standard whose meaning is independent of S’s own wishes and particular intentions). If TC means that S’s change of heart constitutes some kind of waiver or revocation of §9, we would need to know more about how the law of wills provides for such changes. Since the will is formalized, it would seem that some requirement for formalizing waiver or revocation would be essential, lest the living countermand the terms of the will. Problem 2. If we eliminate the waiver or revocation theory, what’s left is the idea that S’s change of heart is evidence that A satisfied the §9 requirement. So reconstructed, TC’s third reason goes like this: evidence that A’s visits to S in the hospital cheered him up supports the conclusion that A was beginning to act “like a lady should” (in one of 5 that vague standard’s possible meanings). But S’s positive response to A’s visits does not imply that A changed any of the other behaviors or aspects of her identity that S found inconsistent with “acting like a lady.” Moreover, A’s threat to sue S’s physician supplies evidence that A’s personality was unchanged, just as S’s displeasure over A’s threat supplies some evidence that S continued to reject A’s lawyerly persona as unladylike. (S could have been displeased, however, for other reasons relating to his health care.) TC views the facts about A’s visits and S’s reactions as evidence that S changed his mind. The “Little Mermaid” story supplies no evidence that S actually did change his mind, though it might be cited to support a normative claim that it is a good thing for fathers to accept their daughters for who they are. From the premise that such a change is desirable, one can’t conclude that such a change actually took place. (As an appellate court, though, we should defer to the trial court’s findings of fact.) In some respects the “Little Mermaid” is ill-suited to TC’s purpose. No doubt S would have been thrilled if A, like the mermaid, loved a Prince and hoped to marry him. Even if the story fit better, though, we might set aside “Little Mermaid” because it is not a law source – not promulgated or enacted by an authorized state lawmaker. The better view may be that some stories are like principles or policies – norms whose authority derives not from enactment but from their power to reveal coherence in a way that guides decision. In Phillip Becker, Judge Fernandez looks to “A Christmas Carol” to illuminate and validate a question of character, responding to the question, “who must the judge be or become when faced with a hard case?” This is not exactly parallel to any use that the TC can make of “Little Mermaid,” since in the latter there is no central role corresponding to the Judge (the Scrooge role in “A Christmas Carol”). “Little Mermaid” is more about the role of father and daughter than about the role of the judge in relation to father and daughter. TC’s use of the Disney version rather than the Andersen version might be a form of self-indulgence, in which the judge gives in to a desire to feel good. But it might be defended as congruent with the “public policy” that TC invokes in reason #2. On this interpretation, TC isn’t trying to say how things really are, either about equality, or gender roles, or about how the value of equal opportunity should be balanced against patriarchal authority, a person’s control over his property, and the limited role of the judiciary in a representative democracy. Instead, TC purports only to speak on behalf of evolving social values, which the more recent (and well-marketed) Disney version expresses better than the Andersen version. 6