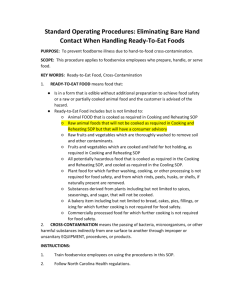

40589k_i&ii 06/21/2002 11:51 AM Page 1

advertisement