Integrated Value Chains

In Aerospace and Defense

Managing relationships and complexity up and down the value chain

T

he aerospace and defense industry is enjoying its strongest

market ever, according to the 2007 Aviation Week A&D Programs

Conference. Demand by the world’s airlines continues to increase,

government defense spending is at its highest in decades, production

is at record levels, the roll-out of new commercial and defense aircraft

continues unabated and more innovative technology is required at a

faster-than-ever pace. Given these dynamics, the industry is compelled

to move toward more integrated value chains—building collaborative

partnerships between manufacturers and suppliers to capture significant opportunities in competitive advantage. The challenge, however,

continues to be managing relationships and complexity in execution.

The phrase “strongest market ever” could suggest

that today’s aerospace and defense industry (the

A&D ecosystem) is demonstrating the bottomline value of collaboration, rapid innovation and

speed to market—all essential earmarks of value

chain integration.1 Collaboration and tighter

integration among manufacturers and suppliers,

with a systems integrator at the lead, is said to

create a more networked, cooperative and productive structure — and drive success in the

market. As these organizations become increasingly networked, both virtually and globally,

mutual success will hinge upon their ability to

gain a competitive advantage from their respective value chains.

Yet being networked into even a simple

supply chain does not mean being integrated into

a value chain. There is a fundamental difference

1

between a networked supply chain and an integrated value chain. In an integrated value chain,

the coordination of external interfaces is just as

important as the coordination of internal interfaces, and technology innovation is a shared

responsibility among all partner companies.

A.T. Kearney’s recent survey of the A&D

industry suggests that value chain integration

is neither universally accepted nor widely practiced. Partnerships in the A&D value chain

are often viewed on a continuum from “transactional supplier or customer” to “fully integrated

strategic partner” (see figure1 on page 2). Prime

integrators, those farthest along in value chain

integration, have partners in most steps of the

value chain. Tier-one contractors have partners

in several steps of the value chain. Tier-two and

-three contractors, those that do not have plans

Value chains are defined as all the interactions that create and add value in the process from innovation, new product development and raw material supply to

finished product and lifecycle support.

A.T. Kearney

|

Integrated Value Chains in Aerospace and Defense

1

to partner in most steps of the value chain, tend to

serve their immediate downstream tier only. The

same research shows an anomaly. Some firms see

their business as predominantly an independent

participant in a networked process. Increasingly, as

companies move upstream into higher tiers, their

perception steadily narrows to focus on fulfilling

orders from the next lower tier rather than understanding their role up and down the value chain.

Such an anomaly is a potent threat to an

industry value chain’s ability to meet its cost, performance and schedule objectives. The success of

any one organization within the industry depends

critically on the performance and capabilities of

others — many others, in most cases. As always,

the weakest link can destroy the chain.

Market-Centric Innovation

Companies are asking their customers what they

want and need. The task is to develop and deliver

the product to market and wow the customer —

and definitely before the product has become

obsolete. But the customer-driven quest for innovation extends far beyond what was once a deciding differentiator, an individual business’s core

competency or technology. The profound com-

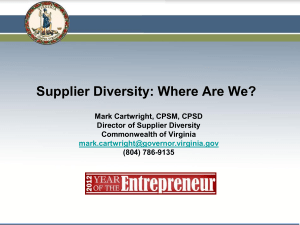

Figure 1

Assessing value chain partnerships in aerospace and defense*

Transactional supplier

or customer

0

Fully integrated

strategic partner

20

40

40

60

80

60

Tier three

80

Tier one

Prime

integrator

Tier two

Transactional supplier or customer

Fully integrated strategic partner

• Pursues mainly buy-sell relationships,

with little or no collaboration

• Focuses on costs and quality

• Does not have formal contracts with

partners

• Maintains hierarchical relationships

along the value chain

• Collaborates with partners and seeks

strategic alignment

• Aligns organization to a value chain

approach

• Values flexibility and offers incentives

to promote it

• Develops relationships along the

value chain

*Companies were evaluated on a scale of 0 to 100 to calculate the degree of integration in the value chain.

Source: A.T. Kearney

2

Integrated Value Chains in Aerospace and Defense

|

A.T. Kearney

100

plexity of today’s products and systems means

that no single firm has the technological, financial

and risk-bearing capability to develop a new airliner or jet fighter, for example, on its own. To try

to do so without teaming across the value chain

would severely constrain the depth, breadth and

speed of innovation.

Today’s A&D customer, the end user,

demands:

• More innovation

• Greater flexibility to incorporate emerging technologies over the system’s life

• Faster time to market

• Managed risk and cost-effective outcomes

• Longer-term product support and service

With this in mind, organizations are moving

across the integrated value chain in an effort to

meet their customers’ needs for more innovative

products. Physical location is becoming increasingly less important as businesses seek strategic

partnerships with global firms offering best-ofbreed technology.

The primes are definitely among the integration leaders. They have mostly moved away

from transactional relationships to assume more

of a value chain integrator role. They are among

the most sophisticated relationship managers

in the group, taking into account a “balance of

trade” among partners.

However, many upstream suppliers still look

at the value chain as a series of discrete suppliercustomer relationships, viewing each transaction

as a separate instance of “buy” and “sell.” The

transactional business, as our survey identifies it,

defines a supply chain simply in terms of buy and

sell transactions at the commodity level. Realize

that although upstream participants may tend

toward the commodity end of the value chain,

they can be costly bottlenecks. Alcoa’s inability to

supply 3/16-inch titanium fasteners, one of the

smallest and least-costly parts on Boeing’s new

787 Dreamliner, was part of a cascading series of

A.T. Kearney

|

production pushbacks. One lesson: In a sophisticated, global, virtual supply chain, the lack of visibility, integration and sophistication far upstream

can prove as troublesome as problems with a hightech, advanced downstream participant.

As customer requirements percolate through

the different tiers of the supply chain, we believe

sustained business growth will be earned by

moving from a transaction-based supplier or customer to a strategic partnership, especially at the

lower tiers of the value chain.

Complexity Is the Issue

Strategically driven partnerships are not without

complexity. Usually, a large number of participants are involved in an integrated value chain,

ranging from strategic partners to transactional

“commodity” suppliers. Relationships among the

participants are multifaceted: One organization

might be buying from another company, selling

to it, selling with it, competing against it, and

engaged in a joint product or service relationship — all at the same time. The word “coopetition,” or cooperative competition, sums up these

complex relationships. As one survey respondent

noted, “Even at our tier of the supply chain, we

are committed to being an integrator, but we

must also keep our manufacturing know-how.”

Just understanding the wide spectrum of

sometimes contradictory relationships at an

enterprise level can become an issue. Managing

the many attendant interdependencies and risks

becomes more difficult, too. Risks are exacerbated

as companies try to implement “lean” supply

chain concepts such as reducing inventories and

tightly synchronizing order-to-delivery times.

Visibility among the participants and across

the value chain becomes increasingly challenging

as system interfaces grow more complex. While

prime integrators can impose their systems to

some degree, they can’t realistically do so for all

supply chain participants.

Integrated Value Chains in Aerospace and Defense

3

On the military side, complexity is compounded due to the International Traffic in Arms

Regulations (ITAR) and other regulations that

impose constraints on supplier eligibility and

information that can be exchanged across supply

chain participants. These restrictions also tend

to limit the open and collaborative product

development style that has become vogue in

other industries.

Is the Integrated Value Chain Universal?

The days of the vertically integrated behemoths

are over. But have companies within the A&D

ecosystem successfully achieved an optimal, integrated value chain characterized by fully functioning partnerships? The answer is yes — and no.

We say “yes” because some companies are

focused on the ultimate customer and use the

value chain as the lens through which they see

the complete process and their unique role in it.

Operating on this inclusive perspective, they can

anticipate change—by seeing it before it gets to

them — and adopt new, fresh and flexible strategies. Such organizations embrace their role and

position in the value chain and use it to their

advantage as a competitive differentiator.

We say “no” because some companies —

too many, we suggest — continue to work the

old transactional system while maintaining an

almost myopic focus. Unable to see any farther than their loading docks, they just don’t

appreciate the potentially disastrous “bullwhip”

effect up and down the value chain of, for

example, a late arrival from their suppliers

or a late delivery to their customers (see figure

2). Such organizations are not committed to

the value chain concept, by decision or default.

Over the long term, their performance or lack

thereof will drive them from the chain.

An important common dimension exists

within both answers. A shortage of commodity

parts at one end of the value chain or a complex

technical problem at the other extreme can have

the same potentially stultifying effect on produc-

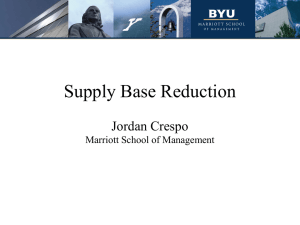

Figure 2

The supplier “bullwhip” effect

Supply fluctuations are magnified as they progress down the supply chain. A little snap of the curve

at the supplier end ripples down toward the customer in successively higher peaks and wider troughs.

Tier-three

supplier

(raw materials

or piece part

manufacturer)

Tier-two

supplier

(component

manufacturer)

Tier-one

supplier

(sub-system

integrator)

Source: A.T. Kearney

4

Integrated Value Chains in Aerospace and Defense

|

A.T. Kearney

Prime

integrator

Customer

tion and delivery to the customer. Best-practice

companies develop solutions commensurate with

the nature and level of the value chain participant

relationship. For example, they may adopt intermediary strategies to deal with possible commodity-level issues at one end while adopting strong

partnership management approaches for the most

complex, expensive and time-consuming issues

at the other end (see sidebar: Best Practices in

Integrated Value Chains on page 7).

For example, Boeing is managing such a

spectrum-spanning situation now, with its fastener shortage at the commodity level and its

wing-box design at the most sophisticated level

of the Dreamliner integrated value chain.

Participants committed to today’s truly

integrated value chain are alert to a number of

interrelated factors. It’s one thing to espouse value

chain integration; it’s another to be an effective

systems integrator attuned to needs such as:

• Bringing new technologies rapidly to bear in

complex systems

• Managing and controlling costs, schedule and

performance

• Focusing on core competencies

• Moving beyond the traditional position in a

system lifecycle

• Incorporating (or at least considering) foreign

sub-assemblies and components to assure access

to foreign markets

Putting More Value in Your Value Chain

An organization that perceives its role as

purely transactional is in an awkward position when “business as usual” can no longer be

the path forward. In the complex A&D ecosystem, business growth requires aligning the

organization to a value chain concept and building relationships up and down the value chain.

With this in mind, the following are proven

approaches that A&D companies can take to

add value to the value chain.

A.T. Kearney

|

Integrate product design and development

with supply chain functions. Realize the fundamental difference between immature and mature

technologies. The more mature the technology,

the less complexity and the fewer changes in

specifications — with a concomitant risk of obsolescence. A program committed to fruition on

the basis of immature technology (“it worked

in the lab, it will work on the production line”)

will be subject to continual change. Usually, the

customer will continue to augment, add, modify

and otherwise keep the design target moving,

which requires the virtual supply chain to be continually flexible. And more often than not, the

longer the development cycle, the more likely the

technology will be obsolete by the time it’s ready

to go to market.

We worked with a North American hightech equipment manufacturer having problems

with on-time deliveries to its customers, whose

needs changed quickly. With our assistance, the

firm developed an integrated value chain based on

two-tier product design criteria — high commonality, lower cost and low commonality, higher

cost. We advised the firm to leverage its local,

more responsive suppliers of critical components

to increase its flexibility and to maintain longer

lead-time relationships for suppliers of predictable, more costly components. As a result, ontime delivery increased to 90-plus percent within

six months, and order lead times dropped from

six to eight weeks to two to three weeks. The

overarching message: Improve your value chain

design. If either your strategy or the competitive

environment has changed and your value chain

design hasn’t, then it’s time for a redesign. This

process enhances the firm’s ability to identify and

establish its distinctive supply chain role — as

prime integrator, sub-system integrator, original

design manufacturer (ODM) or tier-one, -two or

-three contractor — at the product or service value

chain stages.

Integrated Value Chains in Aerospace and Defense

5

Improve supply chain competency. Engage

engineering-savvy people who understand supplier technology road maps and how the pieces

must integrate into a highly functioning supply

chain. Simplified transaction processing is essential to an integrated value chain. In the purchasing

function, for example, paper-based, individualapproval systems can consume valuable management time and can result in costly bottlenecks.

One client reduced its purchase order (PO)

processing time from 30 days to less than one day

by converting to electronic catalogs. The catalogs

contain frequently ordered supplies from approved

suppliers at verified prices, and, in many cases, the

automated approval process is linked to budgeting

tools. Using the catalogs frees the firm’s buyers to

focus on strategic issues instead of managing each

transaction. Significantly, some firms are reducing

their manual efforts by linking their sales catalogs

with their buy-side catalogs. When a sales order is

placed, an order to the corresponding supplier is

triggered automatically if the on-hand supply has

reached predetermined levels. Electronic catalogs,

linked IT capabilities and transaction support

provide sustainable benefits: Our client reported

that 95 percent of its purchases were being done

electronically and PO processing times dropped

to less than a day from almost a month. Customer

satisfaction scores almost doubled.

Increase supply chain visibility. An agreement with a strategic partner can facilitate information sharing, enable technology and increase

communications. In contrast, an agreement with

a transactional supplier can require little more

than efficient transaction execution and helps

assure supply reliability. Strategic partnerships,

therefore, require intense monitoring and managing of all participants. One original equipment

manufacturer (OEM) that outsourced significant elements of the value chain to third-party

suppliers had initially structured all its agreements in a series of “typical” sourcing relation6

ships, basing its service level agreements (SLAs)

on plans to measure the suppliers’ performance.

This “one size fits all” approach led to sub-optimization of the overall supply chain. By restructuring agreements to make them appropriate to the

supplier’s role, it improved alignment among the

suppliers and enhanced the supply chain’s performance. On-time delivery increased from 70 percent to more than 95 percent. Within the SLA,

each business must now also identify the partnership’s value chain governance and operational

principles, including intellectual property sharing

and project management.

Establish solid governance structures. The

best governance structures provide clear responsibilities, accountability and integrated performance

metrics, while recognizing they cannot be entirely

dictated by the prime. Collectively, these structures

must drive system cost, schedule adherence and

performance, and create individual and collective

accountability for end-product results. They must

also recognize that the degree of commitment and

ownership may vary widely among participants.

For example, the $250 billion, nine-nation

development of the Joint Strike Fighter (JSF)

F-35, involving Lockheed Martin, Northrop

Grumman, BAE (SYSTEMS) and scores of other

global suppliers, relies on performance metrics

that change from qualitative to quantitative over

the life of the project. Designed to cover several

major drivers of overall system availability —

mission capable rate, aircraft availability and

mission reliability — the metrics are tied to a

decade-long series of specific milestones along

the JSF development and production lifecycle.

The goal is a system that initially provides a

series of qualitative evaluations of each supplier’s

plan to participate in the program. As the plan

matures, the system switches to a quantitative

evaluation of each supplier’s performance.

Developing metrics that help each partner measure its successes—and identify the lack

Integrated Value Chains in Aerospace and Defense

|

A.T. Kearney

Best Practices in Integrated Value Chains

In a complex environment, survival

often depends on embracing the roles,

responsibilities and opportunities of

an integrated value chain. A handful

of companies in the A&D industry

understand how real integration (and

all it means and requires) can put

more value in the value chain, and

therefore are in a position to achieve

a sustainable competitive advantage.

We recognize best-practice companies as those that do the following:

Monitor and manage both

immediate and upstream suppliers.

Best-practice firms rarely cede management of upstream supply chain

participants to their immediate suppliers because they understand the

risk. Henry Ford’s attempt at vertical integration was intended to

minimize risk and maintain control over the production process,

from raw materials procurement to

product delivery. Boeing’s highly

publicized setbacks with the production of its 787 Dreamliner exemplify the difficulties when upstream

participants do not meet cost, performance or schedule objectives.

A tendency simply to assume that

component manufacturers will

find raw materials —by taking an

“it’s their problem, not mine” attitude — can intensify value chain

risk. Boeing’s setbacks also emphasize how product complexity can

create its own set of problems when

bringing new technology to market.

Find the optimal balance and

supporting governance processes.

Proper governance can reduce supply

chain management complexity while

providing risk management and mit-

igation capabilities. Relationships

and governance processes that

swiftly identify issues and work

cooperatively at resolving them are

essential. Fostering a spirit of give

and take is key, because all suppliers,

whether upstream or downstream,

will need support at some time.

Manage internal and external

interfaces. There is no substitute

for rigorous management of internal interfaces such as customer service, engineering, supply chain and

manufacturing, as well as external

interfaces. This is in contrast to the

firm that must deal with isolated

functional silos and internal departments working at cross purposes.

“Much of the problem we have

with business complexity today is

around internal cooperation and lack

of communication,” said a survey

respondent. “For example, an engineer today has to work more closely

with commodity sourcing, contracting and program management.”

Devise ways to simplify.

Rather than manufacturing products at low volumes that aren’t

attractive to many commercial offthe-shelf suppliers, best-practice

companies build modules (rather

than individual parts) that can

be used in various designs. While

commonality is a way to manage

complexity, it is a significant challenge in the often high-complexity,

low-volume A&D market. However,

opportunities for commonality frequently exist by creating visibility

into cross-program parts, components and sub-systems, and

incentives for reuse.

Do not submit to the pressure to “win” on technology. Bestpractice companies do not apply

technology that is still under development or unproven. Thus, they

do not have to guess at a supposed

(or hoped for) supply base capability to support the technology.

Engage the supply chain function early. Leaders engage the entire

supply chain before the product

development and design function

is well down the path toward producing the product. And they make

certain the supply chain function

has the technical or supply market

knowledge to offer a thorough and

current understanding of supply

options, supplier R&D roadmaps,

and production and supply chain

risks. Leaders also understand that

they must manage the timing and

quality of development and engineering interfaces as closely as the

flow of physical goods and materials.

Develop strategic partnerships.

Such partnerships enable technology innovation, provide for greater

information sharing and assure more

frequent communications. Working

within these strategic partnerships,

best-practice companies efficiently

migrate cutting-edge, technologydriven products and systems from

design to production by supporting

collaboration across the value chain.

A.T.

A.T.Kearney

Kearney | | Integrated

Integrated Value

Value Chains

Chains in

in Aerospace

Aerospace and

and Defense

Defense

7

thereof—requires addressing the implicit need

for a way to evaluate and adapt to integrate new

partners and separate existing ones. At the same

time, each participant’s metrics must ensure that

system-level performance goals are met. If any

supplier fails to perform, then all suppliers will

suffer. A sophisticated exception reporting system

is mandatory.

Employ risk management tools and capabilities. External suppliers are critical elements

in your integrated value chain, which means

managing and mitigating risks must be a central focus. Our studies reveal that as much as half

of the value chain’s cycle time is consumed by

suppliers. The best tools provide for early alerts

far upstream in the supply chain while avoiding

bullwhip effects. For that reason, one electronics manufacturing services (EMS) supplier moved

manufacturing to China to be closer to its electronic components sources. At the same time, some

EMS firms implemented just-in-time manufacturing, switched to batch processing and synchronized

their production with component manufacturers

to respond quickly to changes in the market and

customer demand. In this case, the firm also benefited from lower labor costs for assembly work. By

shipping directly to customer warehouses, EMS

suppliers reduce the length of the integrated value

chain and cycle time, while in many cases eliminating wait times. Moreover, some EMS suppliers

are establishing product development labs closer to

their customers’ R&D centers to develop and roll

out product innovations faster than ever.

How Does Your Role Align with Your Future

Business Strategy?

Look up and down the chain. You will see an array

of partners who coalesce around and are driven by

the following values:

Knowledge of what the customer wants.

Know your role on the continuum in relation to

your specific customer and the ultimate customer.

If you can continually bring a unique product or

service to a partnership, it can probably sustain

your business into the future. But you must be

very good at it, and you cannot be satisfied with

the status quo.

Past dealings or history of the relationship.

If your company has been a reliable member of

the value chain, your prospects for continued

business are excellent. But a word of caution:

If a customer asks for products or services beyond

your capabilities or quality standards, don’t overextend or jeopardize your future. Say no.

Prospects of winning future opportunities

by partnering. Let customers know where you are

in the market and on the continuum. They must

know your capabilities and intentions. If you want

to stay small, you will need to demonstrate how

you can uniquely contribute to innovation,

competitive differentiation and superior cost or

performance to make your other value chain partners successful and your company indispensable.

If you want to grow, you’ll have to commit to

change. You need to begin the process of transforming your value chain — gaining a sustained

competitive advantage in the process.

Authors

Randy Garber is a vice president in the San Francisco office, and can be reached at randy.garber@atkearney.com.

Charles Withrow is a manager in the San Francisco office, and can be reached at charles.withrow@atkearney.com.

8

Integrated Value Chains in Aerospace and Defense

|

A.T. Kearney

A.T. Kearney is a global strategic management consulting firm known for

helping clients gain lasting results through a unique combination of strategic

insight and collaborative working style. The firm was established in 1926 to

provide management advice concerning issues on the CEO’s agenda. Today,

we serve the largest global clients in all major industries. A.T. Kearney’s

offices are located in major business centers in 34 countries.

For information on obtaining

additional copies, permission

to reprint or translate this work,

and all other correspondence,

please contact:

A.T. Kearney, Inc.

AMERICAS

EUROPE

ASIA

PACIFIC

MIDDLE

EAST

Atlanta | Boston | Chicago | Dallas | Detroit | Mexico City

New York | San Francisco | São Paulo | Toronto | Washington, D.C.

Marketing & Communications

Amsterdam | Berlin | Brussels | Bucharest | Copenhagen

Düsseldorf | Frankfurt | Helsinki | Lisbon | Ljubljana | London

Madrid | Milan | Moscow | Munich | Oslo | Paris | Prague

Rome | Stockholm | Stuttgart | Vienna | Warsaw | Zurich

Chicago, Illinois 60606 U.S.A.

Bangkok | Beijing | Hong Kong | Jakarta | Kuala Lumpur

Melbourne | Mumbai | New Delhi | Seoul | Shanghai

Singapore | Sydney | Tokyo

Abu Dhabi | Dubai | Manama

Copyright 2008, A.T. Kearney, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced in any form

without written permission from the copyright holder. A.T. Kearney® is a registered mark of A.T. Kearney, Inc.

A.T. Kearney, Inc. is an equal opportunity employer.

222 West Adams Street

1 312 648 0111

email: insight@atkearney.com

www.atkearney.com

PDF

ATK408041