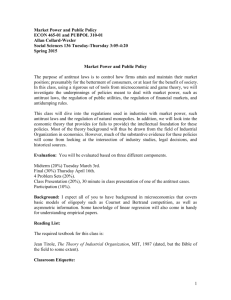

Market Power Without Market Definition

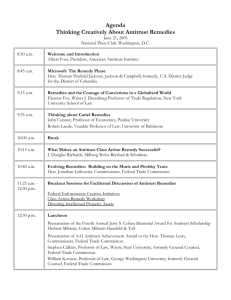

advertisement