C O V E R

S T O R I E S

Antitrust, Vol. 30, No. 1, Fall 2015. © 2015 by the American Bar Association. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved. This information or any portion thereof may not be

copied or disseminated in any form or by any means or stored in an electronic database or retrieval system without the express written consent of the American Bar Association.

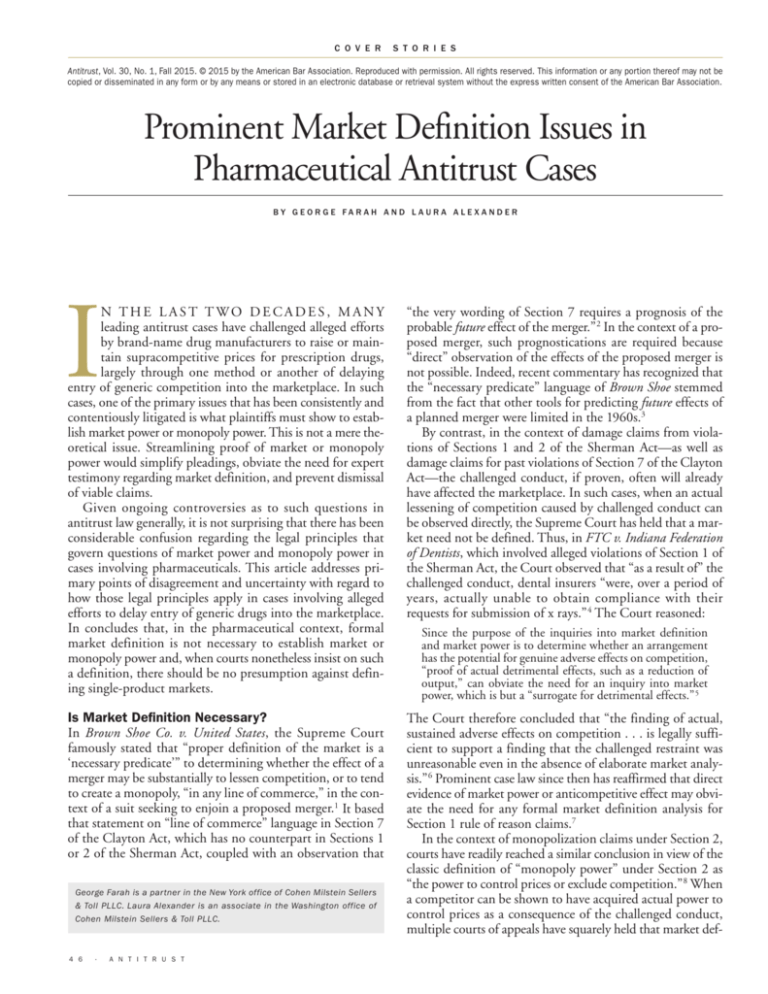

Prominent Market Definition Issues in

Pharmaceutical Antitrust Cases

B Y G E O R G E FA R A H A N D L A U R A A L E X A N D E R

I

N THE LAST TWO DECADES, MANY

leading antitrust cases have challenged alleged efforts

by brand-name drug manufacturers to raise or maintain supracompetitive prices for prescription drugs,

largely through one method or another of delaying

entry of generic competition into the marketplace. In such

cases, one of the primary issues that has been consistently and

contentiously litigated is what plaintiffs must show to establish market power or monopoly power. This is not a mere theoretical issue. Streamlining proof of market or monopoly

power would simplify pleadings, obviate the need for expert

testimony regarding market definition, and prevent dismissal

of viable claims.

Given ongoing controversies as to such questions in

antitrust law generally, it is not surprising that there has been

considerable confusion regarding the legal principles that

govern questions of market power and monopoly power in

cases involving pharmaceuticals. This article addresses primary points of disagreement and uncertainty with regard to

how those legal principles apply in cases involving alleged

efforts to delay entry of generic drugs into the marketplace.

In concludes that, in the pharmaceutical context, formal

market definition is not necessary to establish market or

monopoly power and, when courts nonetheless insist on such

a definition, there should be no presumption against defining single-product markets.

“the very wording of Section 7 requires a prognosis of the

probable future effect of the merger.” 2 In the context of a proposed merger, such prognostications are required because

“direct” observation of the effects of the proposed merger is

not possible. Indeed, recent commentary has recognized that

the “necessary predicate” language of Brown Shoe stemmed

from the fact that other tools for predicting future effects of

a planned merger were limited in the 1960s.3

By contrast, in the context of damage claims from violations of Sections 1 and 2 of the Sherman Act—as well as

damage claims for past violations of Section 7 of the Clayton

Act—the challenged conduct, if proven, often will already

have affected the marketplace. In such cases, when an actual

lessening of competition caused by challenged conduct can

be observed directly, the Supreme Court has held that a market need not be defined. Thus, in FTC v. Indiana Federation

of Dentists, which involved alleged violations of Section 1 of

the Sherman Act, the Court observed that “as a result of” the

challenged conduct, dental insurers “were, over a period of

years, actually unable to obtain compliance with their

requests for submission of x rays.” 4 The Court reasoned:

Is Market Definition Necessary?

In Brown Shoe Co. v. United States, the Supreme Court

famously stated that “proper definition of the market is a

‘necessary predicate’” to determining whether the effect of a

merger may be substantially to lessen competition, or to tend

to create a monopoly, “in any line of commerce,” in the context of a suit seeking to enjoin a proposed merger.1 It based

that statement on “line of commerce” language in Section 7

of the Clayton Act, which has no counterpart in Sections 1

or 2 of the Sherman Act, coupled with an observation that

The Court therefore concluded that “the finding of actual,

sustained adverse effects on competition . . . is legally sufficient to support a finding that the challenged restraint was

unreasonable even in the absence of elaborate market analysis.” 6 Prominent case law since then has reaffirmed that direct

evidence of market power or anticompetitive effect may obviate the need for any formal market definition analysis for

Section 1 rule of reason claims.7

In the context of monopolization claims under Section 2,

courts have readily reached a similar conclusion in view of the

classic definition of “monopoly power” under Section 2 as

“the power to control prices or exclude competition.” 8 When

a competitor can be shown to have acquired actual power to

control prices as a consequence of the challenged conduct,

multiple courts of appeals have squarely held that market def-

George Farah is a partner in the New York office of Cohen Milstein Sellers

& Toll PLLC. Laura Alexander is an associate in the Washington office of

Cohen Milstein Sellers & Toll PLLC.

4 6

·

A N T I T R U S T

Since the purpose of the inquiries into market definition

and market power is to determine whether an arrangement

has the potential for genuine adverse effects on competition,

“proof of actual detrimental effects, such as a reduction of

output,” can obviate the need for an inquiry into market

power, which is but a “surrogate for detrimental effects.” 5

inition is not necessary for a Section 2 claim.9 Leading commentators have largely agreed.10 In particular, at least three

prominent authorities have recently raised compelling theoretical challenges to the notion that formal market definition

is useful to antitrust analysis when market power can already

be shown based on direct, historical evidence.11

In the specific context of antitrust litigation involving

claims of delayed generic entry, principles that support dispensing with any formal market definition requirements

apply even more clearly. When a generic drug comes to market, the price that can be charged for the brand-name drug

invariably plummets by a substantial margin.12 When generic entry has this price effect in the marketplace, some courts

have expressly recognized that the observed price effect by

itself can establish market or monopoly power, without a

need for formal market definition.13 Furthermore, even when

no generic competitor has yet entered the market, some

courts have recognized that the frequency with which generic drug entry sharply depresses brand-name drug prices may

justify a factfinder in concluding that the brand-name company exercises market power prior to generic entry.14

Is Functional Substitutability Enough to Warrant

Inclusion in the Same Product Market?

Despite the principles outlined above and their clear support

in the Supreme Court’s decision in Indiana Federation of

Dentists, some lower courts have continued to treat formal

market definition as though it were a necessary step in establishing market power or monopoly power in pharmaceutical

antitrust cases.15 In many of these cases it is questionable

whether any genuine market definition analysis is required,

as distinguished from analysis of direct evidence of market

power, since the basis for the market definition is often merely the observation that market power exists.16

These cases illustrate one of the principal points made by

Professor Louis Kaplow in recent scholarship, that much of

what passes for “market definition” analysis is really nothing

more than “a purely results-oriented market definition stratagem under which one first determines the right legal answer”

based on direct observations about market power “and then

announces a market definition that ratifies it.” 17 In such

cases, it would be more accurate to recognize that the basis

of the analysis is reliance on direct evidence of market power,

rather than any genuine formal market definition analysis,

and that adherence to any requirement of “market definition”

only tends to obscure the real issues in play.

Nevertheless, when courts have required proof of the relevant market in pharmaceutical antitrust cases, fact issues frequently arise as to whether other drugs in the same therapeutic class should be included in the relevant product

market with the drugs at issue in the case.

The Supreme Court has defined monopoly power innumerable times as “the power to control prices or exclude competition.” The fact that two products may be substituted for

one another functionally should therefore have no bearing on

the presence of market power or monopoly power, absent evidence that such substitutability eliminates the power to control prices.18 By extension, two drugs in the same therapeutic class should not be considered part of the same product

market if competition from the second drug fails to trigger

competitive pricing for the first drug. Accordingly, many

cases in the pharmaceutical context have limited the relevant

antitrust market to the branded and generic versions of a single formulation of a single drug, even when other drugs within the same therapeutic class have been available.19

Courts in a few other cases have reached the opposite

conclusion, in our view based on a misconception as to when

mere functional substitutes should be excluded from the relevant market.20 This confusion arises in part from the ABA

Model Jury Instructions, which state (erroneously, we believe)

that different products should be included in the same product market whenever they are “reasonable alternatives,” without regard to whether competition from one product prevents the manufacturer of the other from raising prices above

a competitive level.21 This approach to market definition is

analytically inappropriate because it does not focus on the

drug maker’s “power to control price,” which is the touchstone for determinations of market and monopoly power.

In the specific context of antitr ust litigation

involving claims of delayed generic entr y, principles

that suppor t dispensing with any for mal mar ket

definition requirements apply even more clear ly.

“Single Brand” Markets

When successful marketing permits a competitor to raise

prices on its products even though others produce essentially identical products, some courts have found it inappropriate to define the successful brand by itself as a distinct product market. Accordingly, in non-pharmaceutical antitrust

cases, “single brand” markets have been generally disfavored

when the products being considered for inclusion in the market are essentially identical.22

It makes no sense to apply these principles, however, where

differences among products do not merely involve brand

names but instead are substantive differences that stem from

patent or copyright protection. Thus, in Fortner Enterprises,

the Supreme Court recognized that one manufacturer’s product can confer economic power “when other competitors are

in some way prevented from offering the distinctive product

themselves. Such barriers may be legal, as in the case of

patented and copyrighted products.” 23

In most pharmaceutical antitrust cases, the branded drug

maker has unexpired patents on the branded drug, along

with corresponding regulatory limitations on the manufacF A L L

2 0 1 5

·

4 7

C O V E R

ture and sale of competing generic drugs under the HatchWaxman Act. Thus, differences between the brand-name

drug and its generic equivalents, on the one hand, and other

drugs in the same therapeutic class, on the other, are not mere

branding differences but instead are substantive differences

stemming from ways in which the law prevents competing

producers “from offering the distinctive product themselves.”

Moreover, prescriptions that physicians write for a particular

brand-name drug may be filled with a generic equivalent

but not by a different drug in the same class. Accordingly,

consistent with the Fortner decision, presumptions against

“single brand markets” should not apply in pharmaceutical

antitrust cases, as some courts have recognized.24

Nonetheless, some courts have applied a presumption

against “single brand markets” in pharmaceutical antitrust

cases even when controlling law—including patent law protection for the brand-name product—prevents rival drug

makers in the same drug class from offering a product identical to the branded drug at issue in the case.25 These rulings

in our view misapply the presumption against “single brand

markets,” which should apply only where there is no legal

hindrance to competing producers selling the same product

as the brand in question.

S T O R I E S

Trading Co., 381 F.3d 717, 736–37 (7th Cir. 2004); Toys “R” Us, Inc. v. FTC,

221 F.3d 928, 937 (7th Cir. 2000).

8

Eastman Kodak Co. v. Image Technical Servs., Inc., 504 U.S. 451, 481

(1992) (monopoly power is the “power to control prices or exclude competition”) (citation omitted).

9

Broadcom Corp. v. Qualcomm Inc., 501 F.3d 297, 307 & n.3 (3d Cir. 2007)

(stating in Section 2 case that “direct proof of monopoly power does not

require a definition of the relevant market”); Heerwagen v. Clear Channel

Commc’ns, 435 F.3d 219, 227 (2d Cir. 2006) (stating in Section 2 case that

“[i]ndirect proof of market power, that is, proof that the defendant has a

large percentage share of the relevant market, is [merely] a ‘surrogate’ for

direct proof of market power” when direct evidence is not available or is

ambiguous), overruled on other grounds by In re IPO Securities Litig., 471

F.3d 24, 42 (2d Cir. 2006); see also King Drug, 791 F.3d at 412; PepsiCo.,

Inc. v. Coca-Cola Co., 315 F.3d 101, 107 (2d Cir. 2002); Re/Max Int’l, Inc.

v. RealtyOne, Inc., 173 F.3d 995, 1026 (6th Cir. 1999); Rebel Oil Co. v. Atl.

Richfield Co., 51 F.3d 1421, 1434 (9th Cir. 1995); United States v.

Microsoft Corp., 253 F.3d 34, 51 (D.C. Cir. 2001).

10

See A NDREW I. G AVIL , W ILLIAM E. K OVACIC & J ONATHAN B. B AKER , A NTITRUST

L AW IN P ERSPECTIVE 919 (2d ed. 2008) (“[E]vidence of the actual ability

. . . [to] raise prices . . . establishes market power . . . and it may do so more

reliably than market share evidence.”); L AWRENCE A. S ULLIVAN & WARREN S.

G RIMES , T HE L AW OF A NTITRUST 74 (2d ed. 2006) (“Disputes about market

definition . . . are of little consequence in the face of actual evidence of anticompetitive effects.”); Phillip Areeda, Market Definition and Horizontal

Restraints, 52 A NTITRUST L.J. 553, 565 (1983) (“[M]arket definition and

market shares are second best to direct measurement.”).

11

Louis Kaplow, Why (Ever) Define Markets?, 124 H ARV. L. R EV. 437, 440

(2010) [hereinafter Kaplow, Why (Ever) Define Markets? ]; U.S. Dep’t of

Justice & Fed. Trade Comm’n Horizontal Merger Guidelines § 2.1.2 (2010),

http://www.ftc.gov/os/2010/08/100819hmg.pdf; Herbert Hovenkamp,

Markets in Merger Analysis; Merger Policy, Structuralism, and the Legacy of

Brown Shoe, 57 A NTITRUST B ULL . 887; see also J. Douglas Richards, Is

Market Definition Necessary in Sherman Act Cases When Anticompetitive

Effects Can Be Shown with Direct Evidence?, A NTITRUST , Summer 2012, at

53–59 (discussing these three authorities at greater length); Louis Kaplow,

Market Definition: Impossible and Counterproductive, 79 A NTITRUST L.J. 361

(2013) (elaborating on prior work and subsequent response); Daniel A.

Crane, Market Power Without Market Definition, 90 N OTRE D AME L. R EV. 31

(2014) (proposing framework for market power analysis in a post-market

definition world). But see Gregory J. Werden, Why (Ever) Define Markets?

An Answer to Professor Kaplow, 78 A NTITRUST L.J. 729 (2014); Gregory J.

Werden, The Relevant Market: Possible and Productive, http://www.

americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/publishing/antitrust_law_journal/at_

alj_werden.aut hcheckdam.pdf.

12

See Eric L. Cramer & Daniel Berger, The Superiority of Direct Proof of

Monopoly Power and Anticompetitive Effects in Antitrust Cases Involving

Delayed Entry of Generic Drugs, 39 U.S.F. L. R EV. 81, 106–08 & nn.86–94

(2004) (citing data showing that entry of generic drugs virtually always

yields much lower prices, so that actions taken to delay generic entry

unquestionably have anticompetitive effects in most cases).

13

See New York v. Actavis, PLC, No. 14-cv-7473, 2014 U.S. Dist. LEXIS

172918, at *101 (S.D.N.Y. Dec. 11, 2014) (“Market power may also be

established by considering evidence of anticompetitive effects of the challenged conduct.”), aff’d, 787 F.3d 638 (2d Cir. 2015); Apotex, Inc. v.

Cephalon, Inc., No. 2:06-cv-2768, 2014 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 131453, at *7

(E.D. Pa. Aug. 18, 2014) (“Monopoly power is ‘the power to control prices

or exclude competition.’ That power may be proven through ‘direct evidence of supracompetitive prices and restricted output,’ or ‘inferred from

the structure and composition of the relevant market.’”) (citations omitted);

In re Nexium (Esomeprazole) Antitrust Litig., 968 F. Supp. 2d 367, 388 n.19

(D. Mass. 2013) (“Where direct evidence of market power is available,

however, a plaintiff need not attempt to define the relevant market.”); In re

Neurontin Antitrust Litig., MDL No. 1479, 2013 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 111587,

at *16–17 (D.N.J. Aug. 8, 2013) (“Plaintiffs have proffered evidence of, inter

alia, Defendants’ costs, Defendants’ lost sales after generic entry, and

Defendants’ sale after generic entry of their own low-priced generic that was

Conclusion

In antitrust litigation involving claims of delayed generic

entry, it should be, and has often been held to be, unnecessary to formally define a relevant market, as market power is

evident when prices invariably plummet in response to generic entry. Some courts in pharmaceutical antitrust cases have

nonetheless required the plaintiff to allege and prove a relevant market. In such circumstances, many courts have appropriately limited the relevant antitrust market to the branded

and generic versions of a single formulation of a single drug,

even when other drugs within the same therapeutic class

have been available and regardless of the general antipathy for

“single brand markets” in the non-pharmaceutical context.䡵

1

370 U.S. 294, 324, 335 (1962).

2

Id. at 332 (emphasis added).

3

Gregory J. Werden, Why (Ever) Define Markets? An Answer to Professor

Kaplow, 78 A NTITRUST L.J. 729 (2014). See also Gregory J. Werden, The

Relevant Market: Possible and Productive, http://www.americanbar.org/

content/dam/aba/publishing/antitrust_law_journal/at_alj_werden.auth

checkdam.pdf.

4

476 U.S. 447, 460 (1986).

5

Id. at 460–61 (quoting 7 P HILLIP A REEDA , A NTITRUST L AW ¶ 1511, at 429

(1986)).

6

Id. at 461.

7

Ball Mem’l Hosp., Inc. v. Mut. Hosp. Ins., Inc., 784 F.2d 1325, 1336

(7th Cir. 1986) (stating in Section 1 rule of reason case that “Market share

is just a way of estimating market power, which is the ultimate consideration. When there are better ways to estimate market power, the court should

use them.”). See also King Drug Co. of Florence, Inc. v. Smithkline Beecham

Corp., 791 F.3d 388, 412 (3d Cir. 2015); Republic Tobacco Co. v. N. Atl.

4 8

·

A N T I T R U S T

nearly identical to Neurontin.”); In re Ciprofloxacin Hydrochloride Antitrust

Litig., 363 F. Supp. 2d 514, 521–23 (E.D.N.Y. 2005) (“In general, to sidestep the traditional relevant market analysis, a plaintiff must show by direct

evidence ‘an actual adverse effect on competition’ . . . . [B]oth Bayer and

Barr expected Bayer to lose significant sales once generic competition

began, with Bayer estimating losses of between $510 million and $826 million in Cipro sales during the first two years of generic competition[.]”); Knoll

Pharm. Co. v. Teva Pharm. USA, Inc., No. 01-C-1646, 2001 WL 1001117,

at *3–4 (N.D. Ill. Aug. 24, 2001) (allegation that brand-name company exercised market power due to patent protection prior to generic entry sufficient

to defeat motion to dismiss).

14

See Actavis, 2014 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 172918 at *101–02 (“Prior to July

2015, Defendants have 100% of the market, there is no competition, development is controlled by Defendants, Defendants’ patent [sic] are absolute

barriers to entry, and demand is inelastic: Defendants have monopoly

power. See generally FOF § IV. Starting in July 2015, however, several generic manufacturers enter the memantine market and Defendants’ memantine

market share is projected to drop below 100%.”); Nexium, 968 F. Supp. 2d

at 389 (“This Court need not engage in an extensive analysis of circumstantial evidence of market power because direct evidence of such power

is available—the Direct Purchasers have thoroughly alleged that AstraZeneca, in its position as a monopolist, has been able to charge supracompetitive prices for brand Nexium.”); FTC v. Lundbeck, Inc., Nos. 08-6381

& 08-6379, 2009 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 62561 (D. Minn. July 21, 2009) (denying summary judgment on the basis that a factfinder may find defendant

possessed market power prior to generic entry).

15

See, e.g., Am. Sales Co. v. AstraZeneca AB, No. 10 Civ. 6062 (PKC), 2011

WL 1465786 (S.D.N.Y. Apr. 14, 2011) (dismissing complaint premised on

market limited to a single PPK, Prilosec OTC); Kaiser Found. v. Abbott Labs.,

No. CV 02-2443-JFW (FMOx), 2009 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 107512, at *26 (C.D.

Cal. Oct. 8, 2009) (rejecting market limited to Hytrin and its generic copies

because it excluded other alpha-blockers); La. Wholesale Drug Co. v. SanofiAventis, No. 07 Civ. 7343(HB), 2008 WL 169362, at *7 (S.D.N.Y. Jan 18,

2008) (product market limited to branded and generic versions of Arava was

cognizable); Mut. Pharm. Co. v. Hoechst Marion Roussel, Inc., No. Civ. A. 961409, 1997 WL 805261, at *2–3 (E.D. Pa. Dec. 17, 1997); Smithkline

Corp. v. Eli Lilly Corp., 575 F.2d 1056, 1064 (3d Cir. 1978).

16

See, e.g., Neurontin, 2013 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 111587, at *10–11 (“The Court

concludes that Plaintiffs must define, at least with a degree of approximation, the relevant market in their analysis under the direct evidence

method.”)

17

Kaplow, Why (Ever) Define Markets?, supra note 11, at 440.

18

See, e.g., Telecor Commc’ns., Inc. v. Sw. Bell Tel. Co., 305 F.3d 1124, 1132

(10th Cir. 2002) (“Reasonable interchangeability does not depend upon

product similarity.”); United States v. Archer-Daniels-Midland Co., 866 F.2d

242, 248 & n.1 (8th Cir. 1988) (sugar and high fructose corn syrup, though

functionally interchangeable, do not reside in the same antitrust product

market); FTC v. Staples, Inc., 970 F. Supp. 1066, 1074 (D.D.C. 1997); In

re Lorazepam & Clorazepate Antitrust Litig., 467 F. Supp. 2d 74, 81 (D.D.C.

2006) (“The fact that products are just functionally interchangeable does

not compel a finding that they belong in the same market.”).

19

See, e.g., Actavis, 2014 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 172918, at *97 (“As in this

instance, courts have found a single brand-name drug and its generic equivalents to be a relevant product market in cases where the challenged conduct involves a branded drug manufacturer’s effort to exclude generic competition.”); Nexium, 968 F. Supp. 2d at 377–88 (“The fact that other drugs

may be used to treat heartburn and related conditions is immaterial to

the present inquiry.”); Andrx Pharm., Inc. v. Elan Corp., 421 F.3d 1227,

1235–36 (11th Cir. 2005) (relevant market limited to controlled release

naproxen); Eli Lilly, 575 F.2d at 1064 (relevant market was cephalosporins,

not other anti-infectives); Wholesale Drug, 2008 WL 169362, at *7 (product market limited to branded and generic versions of Arava was cognizable);

Ciprofloxacin, 363 F. Supp. 2d at 522–23 (relevant market limited to drug

product ciprofloxacin, not other flouroquinolone antibiotics); In re Terazosin

Hydrochloride Antitrust Litig., 352 F. Supp. 2d 1279, 1319 n.40 (S.D. Fla.

2005) (relevant market limited to branded and generic terazosin hydrochloride); Knoll Pharm., 2001 WL 1001117, at *3–4 (product market limited to

hydrocodone bitartrate/ibuprofen was cognizable); In re Cardizem CD Antitrust Litig., 105 F. Supp. 2d 618, 680–81 (E.D. Mich. 2000) (approving product market limited to branded and generic versions of Cardizem CD);

Hoechst, 1997 WL 805261, at *2–3 (relevant market could be limited to

Seldane, and excluded Claritin, because of unique formulations).

20

See, e.g., Bayer Schering Pharma AG v. Sandoz, Inc., 813 F. Supp. 2d 569

(S.D.N.Y. 2011) (dismissing complaint premised on market limited to oral

contraceptives containing drospirenone); American Sales, 2011 WL

1465786 (dismissing complaint premised on market limited to a single

PPK, Prilosec OTC); Kaiser Found., 2009 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 107512, at *26

(rejecting market limited to Hytrin and its generic copies because it excluded other alpha-blockers); Asahi Glass Co. v. Pentech Pharm., Inc., 289 F.

Supp. 2d 986, 996 (N.D. Ill. 2003) (Posner, J., by designation) (stating that

it “cannot merely be assumed” that Paxil does not compete with other antidepressant medications).

21

See ABA M ODEL J URY I NSTRUCTIONS IN C IVIL A NTITRUST C ASES , at C-7 (“[I]f

consumers seeking to cover leftover food for storage considered certain

types of flexible wrapping material—such as aluminum foil, cellophane, or

even plastic containers—to be reasonable alternatives, then all those products would be in the same relevant product market.”).

22

See Pioneer Family Invs., LLC v. Lorusso, No. CV 14-00594, 2014 WL

2883058, at *5 (D. Ariz. 2014) (“Generally, a relevant market in a monopolization action cannot be limited to the products of a single manufacturer.”)

(citation omitted); Dang v. S.F. Forty Niners, 964 F. Supp. 2d 1097, 1105

(N.D. Cal. 2013) (“Defendants are correct that single-brand markets typically

do not constitute legally cognizable markets for the purposes of an antitrust

suit.”); U.S. Ring Binder L.P. v. World Wide Stationery Mfg. Co., 804 F. Supp.

2d 588, 598–99 (N.D. Ohio 2011) (rejecting market limited to single company’s ring binder products); Apple Inc. v. Psystar Corp., 586 F. Supp. 2d

1190, 1198 (N.D. Cal. 2008) (“Single-brand markets are, at a minimum,

extremely rare.”); Green Country Food Mkt., Inc. v. Bottling Grp., 371 F.3d

1275, 1282 (10th Cir. 2004) (“In general, a manufacturer’s own products

do not themselves comprise a relevant product market. . . . Even where

brand loyalty is intense, courts reject the argument that a single branded

product constitutes a relevant market.”); Hack v. President & Fellows of Yale

College, 237 F.3d 81, 86–87 (2d Cir. 2000) (housing at a single university), abrogation on other grounds recognized by Diamond v. Local 807 Mgmt.

Pension Fund, 595 Fed. App’x 22, 25 (2d Cir. 2014); Flash Elecs., Inc. v.

Universal Music & Video Distrib. Corp., 312 F. Supp. 2d 379, 391 (E.D.N.Y

2004) (specific movies); Mathias v. Daily News, L.P., 152 F. Supp. 2d 465,

482 (S.D.N.Y. 2001) (specific newspaper); Shaw v. Rolex Watch, U.S.A., Inc.,

673 F. Supp. 674, 679 (S.D.N.Y. 1987) (Rolex watches); Deep S. Pepsi-Cola

Bottling Co. v. Pepsico, Inc., No. 88 CIV. 6243, 1989 WL 48400, at *8

(S.D.N.Y. May 2, 1989) (distribution of a single soft-drink brand).

23

Fortner Enters., Inc. v. U.S. Steel Corp., 394 U.S. 495, 505 n.2 (1969).

24

See URL Pharma, Inc. v. Reckitt Benckiser, Inc., No. 15-505, 2015 WL

5042911, at *6 (E.D. Pa. Aug. 25, 2015) (holding that “a single product

may, in some cases, constitute a separate relevant market” and citing several pharmaceutical cases in support); Actavis, 2014 U.S. Dist. LEXIS

172918, at *97 (“As in this instance, courts have found a single brandname drug and its generic equivalents to be a relevant product market in

cases where the challenged conduct involves a branded drug manufacturer’s effort to exclude generic competition.”); Cardizem, 105 F. Supp. 2d at

680 (“[A] single brand of a product can constitute a relevant market for

antitrust purposes.”); Hoechst, 1997 WL 805261, at *3 (“The Supreme

Court has held that in some instances a single brand of a product may constitute a relevant market or a separate submarket.”).

25

See, e.g., Bayer Schering, 813 F. Supp. 2d 569 (dismissing complaint

premised on market limited to oral contraceptives containing drospirenone);

American Sales, 2011 WL 1465786 (dismissing complaint premised on

market limited to a single PPK, Prilosec OTC); Kaiser Found., 2009 U.S. Dist.

LEXIS 107512, at *26 (rejecting market limited to Hytrin and its generic

copies because it excluded other alpha-blockers); Asahi Glass, 289 F. Supp.

2d at 996 (Posner, J., by designation) (stating that it “cannot merely be

assumed” that Paxil does not compete with other antidepressant medications).

F A L L

2 0 1 5

·

4 9