a Product of the Renaissance? The Legal Facilitating, Appropriating

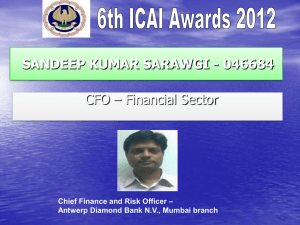

advertisement