Counsel for the Poor

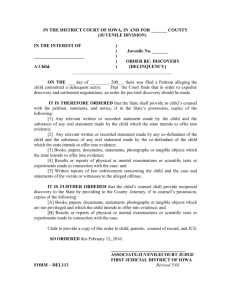

advertisement