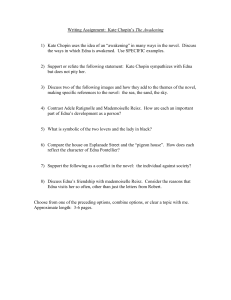

The Awakening - Anderson School District One

advertisement